Reading Tintin in the Library | Guest Essay

Today we have a guest essay by Dave Baker, a cartoonist and the creator of the YA graphic novel Forest Hills Bootleg Society and the upcoming Mary Tyler Moorehawk, due out in February from Top Shelf.

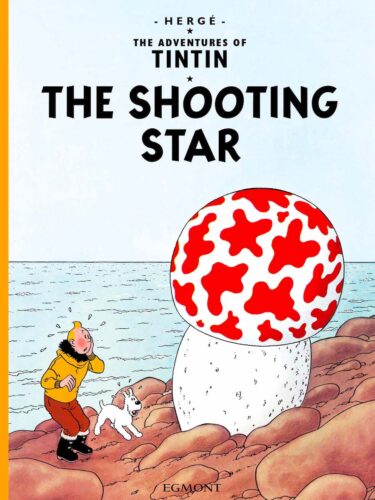

What does that have to do with Tintin? That’s what this essay is about: Baker writes about how the librarian who recommended a Tintin graphic novel to his mother changed his life, setting him on course to become a cartoonist and storyteller himself. And what better time to reflect on that than on Tintin’s 95th birthday? The Belgian reporter and adventurer debuted in the children’s magazine Le Petit Vingtieme on January 10, 1929, making the first appearance in his long and colorful career.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Without further ado, here is Dave Baker’s essay. Enjoy!

How The Library System Changed My Life

I pride myself on being an honest and forthright individual. Because of that, I’m going to be honest with you, Dear Reader. Tucson, Arizona isn’t exactly the hotbed of global culture. And it definitely wasn’t when I was a kid in the 1990’s.

Arizona, in general, is one of those places that just makes you sit back and wonder… “Was it a good idea for humans to live here?” Like, I know rent is cheap… but at what cost? When is an affordable cost of living offset by the environment trying to kill you? In fact, one of my first memories is not understanding just how hot the asphalt gets in the summer, and attempting to walk barefoot on it, on a particularly warm day… and receiving burns on the soles of my feet for this grave miscalculation.

As such, you spend a lot of time indoors in Arizona. Especially during the summers. During that time of year, just existing without air conditioning is a full contact sport.

Due to that, you find ways of entertaining yourself that have the highest proximity to air ducts and coolant systems possible. For me, that manifested as being obsessed with two things: books and drawing. I learned to read a bit late in life. However, I was obsessed with the written word from just about the word go.

As a young child, I was specifically utterly consumed by the Boy Adventurer and Girl Detective genres. Nancy Drew, Trixie Belden, the Boxcar Children, Tom Swift Jr, and the Hardy Boys. Anything involving young kids roaming around solving mysteries or going on adventures? I was there.

And here’s where the random chaos of life, occasionally, works in your favor. One day, while at our local library, my mother struck up a conversation with one of the librarians and inquired about more book series in the Nancy Drew or Hardy Boys mold. This librarian, the saint that they were, suggested Herge’s The Adventures of Tintin. It changed my life forever.

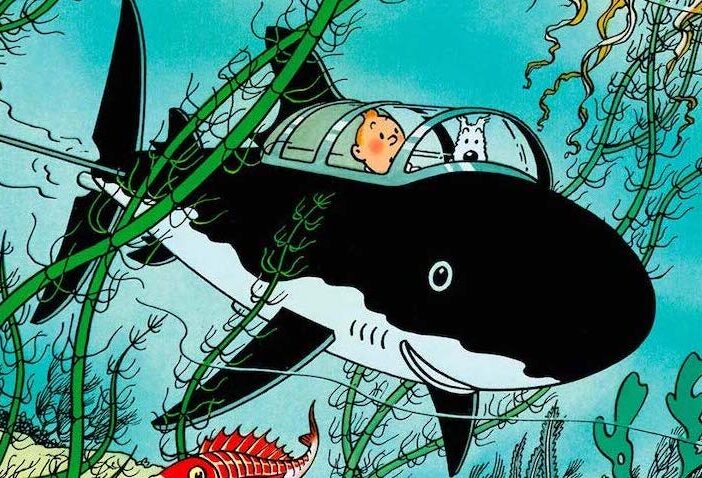

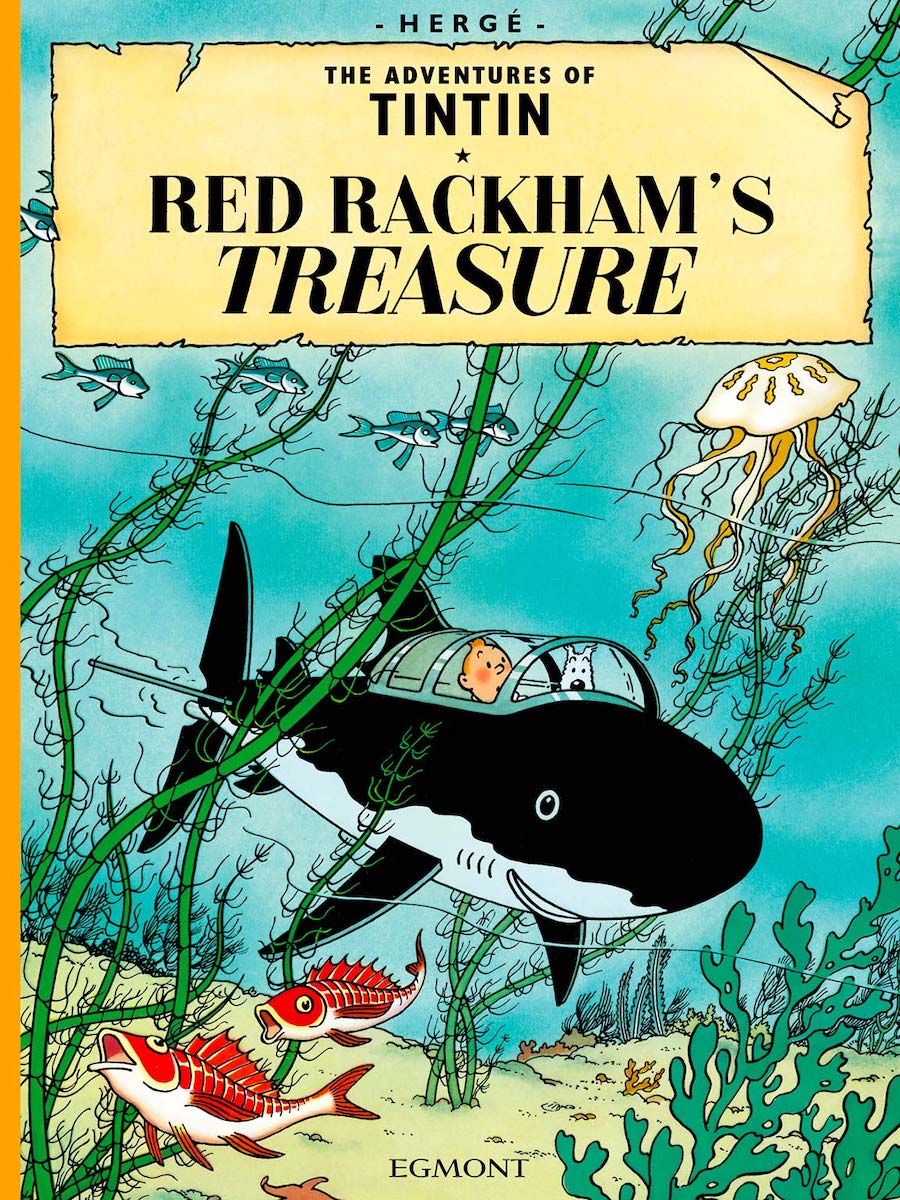

For anyone who doesn’t know, Georges Remi—or as he’s known professionally—Herge, was a Belgian cartoonist who spent most of his life creating stories about a young boy reporter named Tintin. Along with his dog Snowy, Tintin traveled the globe, solved crimes, and even made it to the moon, believe it or not. While Tintin has never really taken off in the States, in Europe he’s massive. Bigger than Mickey Mouse.

And to me? As a kid? That was an inarguable fact. Tintin was my idol and my conduit to creativity. After experiencing the first couple volumes, I became completely obsessed with the idea of writing and drawing comics. The fact that this was a book, about a kid adventurer, and I could actually see what was happening, not just imagine it? It was nothing short of a complete revelation to me.

And the fact I could do it inside made it all the better.

The thing that has never quite made sense to me is why this library in the middle of nowhere had a complete collection of every Tintin book, or at least the non-problematic ones that the Herge estate has allowed to be translated into English. And on top of that, the odds that a librarian who was familiar with the character, genre, and medium of comics was also employed there seems to be statistically incalculable.

And yet, the cosmos moves in mysterious ways, sometimes.

I’ve often thought back on my obsession with the genre of Kid Detectives and Adventurers and tried to parse what exactly it was that drew me to them at a young age. And I think that this genre is secretly highly subversive. If you actually think about what the underlying moral is of almost every Nancy Drew or Hardy Boy story is… it’s “the adults are lying to you.” or “Only the children see the truth.”

Think about it. The villains are always adults who are attempting to get away with some dastardly land grab, revenge-fueled murder, or underhanded swindle. They’re always a member of the cast that has a tangential connection to the protagonist, and when our main character begins to suspect something is afoot, none of the other adults want to believe that something like this could be real. The adults are always in league with one another, and it’s the primal truth of the situation that is only ever evident to individuals sub-fifteen years old.

This is an elemental reality to young people. When things aren’t right as a kid, you just know. When something’s off, you can feel it. Your emotional intelligence is heightened because your experiential knowledge is handicapped. You live in this third state of evidentiary quantum entanglement as a young person.

This theme is represented in almost every depiction of these types of characters. Think about it: Nancy Drew looking off camera into a darkened hallway, posing in front of a grandfather clock. The Hardy Boys pointing a flashlight into a spooky treeline. These images, usually painted by famed artist Rudy Nappi, have a single unifying visual motif: The children are always looking. They’re looking at something, for something, or around something. Children’s ability to perceive is the ultimate wish fulfillment of the genre in question, in my opinion.

And to bring this full circle, that’s what the Pima County Library System gave me. It gave me the ability to see beyond my circumstances. It gave me exposure to the artform I would dedicate my life to. And it gave me an awareness outside of myself.

This message feels prescient now, more than ever, maybe. In a day and age when calls for censorship and book burnings are so common they feel like they feel like we’re living through an extended and deeply unfunny Saturday Night Live sketch, championing libraries is a vital cornerstone of the lifeblood of our culture.

Access to information, literature, and culture should be every citizen’s right, regardless of race, creed, or, in the case of this anecdote… age.

Books exist in an inert state for the majority of their lives. It takes a human mind to take the words and synthesize them into a functioning experience. This is the deeply human contradiction that some people are afflicted with. Nothing housed in a book can hurt you, if you are not the one who chooses to engage in that task of synthesis. Therefore, being afraid of new ideas and attempting to remove them from our collective houses of knowledge is an inherently foolish and selfish endeavor.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

There are countless books I have no interest in reading, or that I think house ideas that aren’t productive. But I don’t spend my time attempting to keep them out of our collective understanding. That way lies madness. Instead, I choose to spend my time exalting the things that have inspired me and contribute positively to my social ecosystem.

Who would I be if the library didn’t grant me access to countless fictional worlds? How would my trajectory of existence been lessened if that chance encounter with a librarian talking to my mother and flippantly suggesting I might like a Belgian comic strip from the 1940s had never happened? This is a truly existential nightmare to me. And the fact that there’s a potential for this dark mirror universe to manifest for young people all across the country, if we don’t collectively stand up and say that it’s important for school libraries to carry a wide selection of material or for local libraries to carry books that parents don’t always understand, chills me to my core.

The thing that truly boggles my mind is that I’m one person out of thousands that went in and out of those library doors. And that was one library in my county? The positive cultural change that libraries enact on their communities is immeasurable and incalculable. The only downside is that there is no immediate financial receipt for evolving the souls of young people. It’s labor that bears fruit decades later. But that delayed gratification is no marker of an endeavor that is less worthy. In fact, it is more so. It is the work of public servants who want nothing in return, aside from personal evolution. If that is not the highest and most altruistic cause, I don’t know what is.

Here we are, decades later, and I can say beyond a shadow of a doubt that I would be a significantly diminished individual if it were not for my local library. Shouldn’t that be enough? Shouldn’t the fact that the library system has the potential to fundamentally rewrite someone’s spiritual DNA be enough for us to keep supporting the great experiment that Benjamin Franklin dreamed up all those years ago? I think so. But, then again, I’m a bit biased.

Filed under: Opinion

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Report: Newberry and Caldecot Awards To Be Determined by A.I.?

Happy April-Fool’s-First-Day-of-Poetry-Month! A Goofy Talk with Tom Angleberger About Dino Poet

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Fast Five Author Interview: Naomi Milliner

ADVERTISEMENT

Thank you for sharing this lovely childhood anecdote. I, too, grew up as a lover of Tintin, and even ended up writing a final paper on it for a children’s literature class – in a time when I found the canon of children’s literature to be so one-sided and non-representational. In college, I discovered that our university library had the entire collection, so I diligently read all of the series, including the abecedaire. When I traveled to France, I found the much-discussed and censored in America, Tintin in the Congo, which is a blatantly racist and colonial narrative reflecting the colonial attitudes of the Belgian colonization and enslavement of the people of Congo. It’s then that I started re-examining the depiction of indigenous, Asian, Middle Eastern, etc. tropes in the books, and found them to indeed be problematic. So I exist now in these halves…one of having cherished Tintin as a child, but as an adult, and a librarian, unable to share these titles with my younger patrons because of their problematic depictions of marginalized groups. I’m wondering if you’ve encountered this…or what your thoughts on this would be.

Hi, Mina!

Thank you so much for you thoughts on this issue. To put is shortly, yes. I have encountered Herge’s “problematic side” and I feel largely similar to you, with one slight deviance. I think there are large swaths of his work that feels passively or subconsciously racist. And then, certain elements of his work that is outright and pointedly bigoted.

Like all humans, Georges Remi was deeply flawed. His preconceived notions and privilege halted his innate sense of curiosity on multiple fronts. From his frequently wrong-headed depictions of people of color to his continuing to work for his catholic newspaper after the Nazis took it over during the second World War, and the increased depictions of codedly jewish antagonists during this time period, Herge made many decisions that I don’t agree with.

This all being said, I think it’s important to have these conversations with children and readers of all ages. And also to shine a light on his mistakes as a person, so we can all attempt to learn and grow.

Personally, I think the dichotomy between the various “eras” of Herge are a fascinating conundrum. His evolving and devolving politics, his messy divorce and marrying one of his coloring assistants, and the previously mentioned racist/fascist inclinations are all areas worthy of discussion, to me.

However, I would add that, to me, this is not a case where the artist is irredeemable. Herge seemed like someone who was complicated, flawed, and always looking for a path forward. It’s also interesting to me to highlight for a second his more progressive elements.

I’m sure you already know this, but I’ll lay this little anecdote out for you. For Tintin’s fifth outing it was announced in many news papers that his next adventure would take place in Asia. This drew the attention of Chinese art student, studying in Brussels namend Zhang Chongren, who often just went by the shortened name Chang. This man would ultimately be the inspiration for the beloved Tintin character Chang Chong-Chen. Chang reached out to Herge, writing him a letter, and telling him that he wished to meet and express that it was important for Herge to “get the details right” in this book that was rumored to take place in China. They did meet, and Chang conveyed to Herge just how important it was to depict the reality of the world, how showing people and places inaccurately had real world consequences, and that his racism in the past had been something that had affected how Westerners viewed the various cultures that had already been depicted in the books. This revelation, connection, and friendship that spawned from this relationship would impact the books, and specifically Blue Lotus immeasurably.

Chang exposed Herge to Eastern ideas like Buddhism, Taoism, and literally taught him three-point perspective. Chang also co-drew the Blue Lotus with him, writing all of the street signs and designing almost all of the costumes and fashion that appears in the book. Furthermore, Chang’s influence can be felt in the fact that the book mocks intolerance and bigotry and Western ideas of what life in china is like. Thompson and Thomson at one point are the brunt of the joke when they have preconceived ideas of how Chinese people dress, and ultimately these ideas are wrong and backwards, to comic effect.

Additionally, the intricacies of Sino-Japanese War, which is at the heart of the story, was being shied away from being covered in mainstream news outlets, is my understanding. Now, admittedly, this is a bit beyond my personal historical knowledge. But my rough understanding here is that Herge was actually doing a good job both in his depiction of the specifics of the war and also of his depiction of the surrounding context, by delving into multiple subject that Western media did not want to acknowledge or touch on. Specially, how prisoners of war were being held and treated.

Blue Lotus is a towering achievement in Herge’s body of work and Chang is an integral part of both Herge’s artistic growth and personal evolution. Now, there’s many ways to look at Herge’s life, but to me, this specific period is one of the most important. It’s the opposite of his Father Wallez period. (the catholic priest who ran the newspaper that Tintin was published in, who was a rampant bigot and encouraged many of Herge’s more negative tendencies early in his career) To me, this period in Herge’s life is a testament to the power of artistic expression. And how you can attract people through your art that will spot your weaknesses, call you out on them, and assist you to grow and mature. It’s about the magic of comics as a tool for spreading ideas, and how that comes with an immense responsibility.

I don’t think there’s a wrong way to go about this. For some people, the complication and damaging things Herge did and was responsible for subsume the positive. For me, I’d rather look at the work and the individual in question with as clear a perspective (no pun intended) as possible. I think the work is obviously important, look at the fact that we’re still talking about it almost 100 years later. I think the man who made it went through multiple waxing and waining political periods, some of which I think are deeply shameful. And I think, at his best, he was someone who listened, tryied to improve, and attempted to evolve. And that’s admirable.

I know this is something of a long winded answer, but your question was thought provoking and well-considered, so I felt that it deserved an emotionally honest answer.

Hello, Dave!

Thank you so much for adding so much context and offering such a nuanced perspective. I love addressing the complexities of Hergé’s personhood and that anecdote about The Blue Lotus is incredible. I did notice a marked difference with that book relative to Tintin in America and Tintin in the Congo. As a person of Asian descent, and one from a country that was formerly colonized by Japan, I did recognize those subtleties, though I couldn’t name them outright in the moment. Even as a younger reader, I knew that there was something to be cherished and appreciated in these comics, though I didn’t always know why. And I think this is what I hang on to as an adult.

On a wholly separate note, I did get a chance to go to the Hergé Museum in Brussels and smiled like a little kid the whole way through. While they didn’t necessarily address the ideological journeys of his life (or maybe I missed it), I did find myself fascinated with him as a prolific author with a profound curiosity of the world. May I ask where your depth of knowledge of Hergé comes from?

Thank you again for the fidelity and robustness of your response. It’s such a breath of fresh air to have dialogue in an age when things seem only to be black and white.