Interview: Meryl Jaffe on Comics and Education

When I was doing research for this month’s SLJ article on comics in schools, I had the opportunity to talk to a number of experts on the topic, including researchers, teachers, and school librarians. And as anyone who has ever written a story like this, or been interviewed for one, knows, only a fraction of those interviews goes into the finished piece.

Buy hey, we’ve got a blog!

All this week, I’ll be posting the interviews I did for the article. We’re kicking it off with a long, but very informative, e-mail interview I did with Meryl Jaffe, who is an instructor at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth, Online Division, and the author of Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

GC4K: How do you see teachers using comics—as instructional materials on a given topic, as supplementary reading, as literacy aids for reluctant readers, or to be read as literature in your own right? Which of these do you think are most appropriate? Which would you like to see more of?

Meryl Jaffe: Every which way! Comics and graphic novels should and are being increasingly used in classrooms both as central texts for language arts classes, as supplementary reading, and as literary aids for reluctant readers and weak language learners. They not only invite and empower students of diverse learning needs, they reinforce multi-modal learning, multi-modal literacy, and brilliantly address many of the Common Core Standards. In my ideal classroom graphic novels, interviews, speeches, scripts, video clips, and classic texts are all used together to teach the art and power of communication, entertainment, and rhetoric, to more broadly empower our students to better understand and conquer the worlds around them.

Comics and graphic novels, however, have struggled and gotten bad reps. While they used to entail the weekly strips or short bound issues of Archie, detectives or superheroes—all entertaining, but not exactly up there with Jane Austen—they’ve changed considerably over the last few decades and they deserve a closer look. The art, language, and content of kids’ graphic novels today is quite extraordinary and they most definitely have a place in 21st-century classrooms. They show and tell the art of metaphor and storytelling, they show and tell character and plot development, they show and tell facts and fictions.

Graphic novels incorporate visual and verbal literacy across various formats, genres, and text structures. By their very nature, comics and graphic novels draw the reader into the story both through their alluring art and through the need for readers to actively construct the stories as they integrate (often) divergent visual and verbal information. And many can and are taught as primary texts. But it gets even better—pairing graphic novels with prose novels, speeches texts, and primary sources allows for comparative discussions on format, word usage, literary style, text structures, and design. By teaching prose and graphic texts side by side, you involve visual and verbal learners, making learning more meaningful as students actively work, comparing and analyzing diverse texts and their affects. Using the mixed-medial texts also gives weaker language learners more footing and opportunity to participate and become more actively involved in discussions and projects.

Let’s take a closer look—evaluating how comics and graphic novels can help teachers affectively integrate Common Core Standards, while also understanding how these books can help meet students’ diverse learning needs.

THe Common Core Standards say that reading instruction must now address “Key Ideas and Details; Craft and Structure; Integration of Knowledge and Ideas: Range of Reading; and Levels of Text Complexity.” Here’s just a quick look at how graphic novels help teachers meet these standards:

- Graphic novels typically use concise (and often advanced) vocabulary and the paired images help readers define and remember the words (addressing Range of Reading).

- Their concise language and sequential story panels help readers clearly distinguish between main ideas and details. This is especially helpful for young readers who so frequently have trouble with this task – the images help make the task more concrete and more manageable (addressing Key Ideas and Details, Craft and Structure).

- Pairing and comparing prose and graphic novels will also provide a means to compare, evaluate, and contrast different forms of texts and text structures. Furthermore, many classic books can be read in prose and graphic novel formats (for example A Wrinkle in Time (by Madeleine L’Engle, graphic novel adapted by Hope Larson), The Ember City (by Jeanne DuPrau, graphic novel adapted by Dallas Midddaugh, art by Niklas Asker), Frankenstein (by Mary Shelley), and many of the classics now in public domain). Comparing these stories across formats directly addresses Common Core Standards (addressing Key Ideas and Details, Craft and Structure, Range of Reading and Text Complexity).

- As themes, ideas, characters and events are developed in a visually sequential manner, it is easy to chart their development (addressing Key Ideas and Details, Craft and Structure, Integration of Knowledge and Ideas).

- Graphic novels can (and should) also be used in social studies to provide perspectives and discussions relating to National Council for Social Studies Teaching Standards: Culture and Cultural Diversity; Time, Continuity and Change; People, Places and Environments; Individual Identity and Development; Power, Authority and Governance; Production, Distribution and Consumption; Global Connections; and Civic Ideals and Practices)

But, before diving in, I want to clarify “comic.” I see a comic as a the awesome strips I grew up with, Charles Schultz’s Peanuts, Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes, Berkeley Breathed’s Bloom County and Gary Trudeau’s Doonesbury, to name my favorites. And there is most definitely a place in classrooms for these comics. While Doonesbury was very much a comic reflecting the political arena of the 1960s-1980s, the others are wonderful comments on everyday life. As such, they can be used to supplement lessons around the Vietnam War (Doonesbury), or they might be great tools to introduce works of philosophy, or even to help students dig into chapter books in language arts. Whether teachers have students read comics to introduce metaphor, simile, irony, or any other literary tool or thematic concept, or whether they have students create their own comic (to summarize, present, or reflect a specific theme or concept), comics most definitely have a place in the classroom.

The thing is, though that now in addition to comics, we have outstanding graphic novels, which I believe you are asking about. Graphic novels are stories told much like comics through the use of text balloons and sequential art. They ARE comics, but they are bound and typically tell a long(er) story, be it fiction, non-fiction, fantasy, mystery, science-fiction, or romance. Graphic novels’ short bursts of text (often in fun fonts) and vivid images make reading, classroom participation, and most curriculum come alive for all kinds of readers and language learners, and therefore they are serving increasingly central roles in language arts classrooms. Integrating multi-modal forms of literacy empowers more learners. Incorporating graphic novels help empower weak language learners, who find the reading less daunting and participation in classroom discussions and activities more accessible. Furthermore, there is a growing number of outstanding non-fiction graphic novels that should be used in language arts, science and social studies classrooms.

For weak language learners and readers, graphic novels’ concise text paired with detailed images help readers decode and comprehend the text. Reading is less daunting (with less text to decode) while vocabulary is often advanced, and the concise verbiage highlights effective language usage. Furthermore, the images invite and engage all readers. For skilled readers, graphic novels offer a different type of reading experience while modeling concise language usage. Because the text has to be succinct, graphic novels model how to efficiently communicate stories and ideas in short, pithy text. For these reasons alone, graphic novels are increasingly taking center stage in language arts classes.

Graphic novels are also outstanding tools to help teach and illustrate abstract concepts or distant events kids have trouble relating to, and their graphic, interactive texts can be used across content-areas. For example, there is an excellent graphic novel (grades 5+) about the United States Constitution called The United States Constitution: A Graphic Adaptation by Jonathan Hennessey and Aaron McConnell. This book not only clearly explains and details the Preamble, Articles of the Constitution, its Ratification (appeasing both Federalists and Anti-Federalists), The Bill of Rights (Articles 1-10) and the additional Amendments (11-27), it does an outstanding job of explaining the thought and details the framers wrestled with when dealing with the balance of powers and lobbyists. It is truly an outstanding work that belongs as primary reading in language arts and social studies classrooms.

Another example of an outstanding graphic novel that can be used across content-area is Ho Chi Anderson’s King (I would recommend this for high school and older as there is some inference to infidelity). This book contains interviews, background history on King and the Social Rights Movement, addresses violent versus non-violent protest, and contains Kings speeches as well as conversations with President Kennedy and other historical leaders. As the text formats vary within this book, it can be used to teach various non-fiction text formats while appealing to students of various skill levels. And, Anderson’s powerful art, just makes it all come alive – literally!

But the list goes on. Some of my favorite non-fiction graphic novels include:

- Nick Abadzis’ Laika, about the space race from the Russian perspective and their efforts to get the first sentient being (the dog, Laika) up into space (grades 4+);

- Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi, about life in Iran (pre and post revolution) (grades 9+);

- Zahra’s Paradise, a graphic novel about the life and turmoil in Iran during protests of 2009 (grades 9+);

- Hidden: A Child’s Story of the Holocaust, by Loic Dauvillier, about how the author was hidden as a young girl, surviving the holocaust (grades 6+);

- Lewis and Clark, by Nick Bertozzi (grades 4+);

- Journey into Mohawk Country, by George O’Connor, tells the story of Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert who (based on his original journal) who at age 23 ventured into Mohawk territory with guides, maps and some food, trekking through freezing temperatures to revive the struggling fur trade (grades 4+);

- Marathon, by Boaz Yakin and Joe Infurnari, tells the story of Eucles and the (ancient) Battle of Marathon (grades 4+);

- Jerusalem: A Family Portrait, a memoir by Boaz Yakin with art by Nick Bertozzi, about Yakin’s family living in Jerusalem (and torn apart politically) during the fight statehood in the 1940s (grades 6+);

- Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller, by Joseph Lambert (grades 3+);

- The Olympians series on Greek mythology, by George O’Connor (grades 4+),

- Books about the civil rights movement such as March, by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell (grades 5+), and The Silence of Our Friends, by Mark Long, Jim Demonakos and Nate Powell (grades 5+), a story about Mark’s father, a reporter in Texas during the 1960’s, to name just a few.

- Feynman, by Jim Ottaviani and Leland Myrick relating the life of Nobel Physicist Richard Feynman (which can be used in science, language arts and social studies) (grades 8+);

- Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas, by Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wicks, about these three pioneering women and their studies/observations of primates (grades 4+).

There are also outstanding historical fiction graphic novels such as:

- The Resistance series, by Carla Jablonski and Leland Purvis, about France during German occupation in World War II (grades 5+);

- City of Spies, by Susan Kim and Laurence Klaven, about life in New York City in the summer of 1942 (grades 3+)

- Little White Duck, by Na Liu and Andres Vera Martinez, a collection of eight stories based on the author’s childhood in China during the 1970’s and 1980’s (grades 5+);

- Dogs of War, by Sheila Keenan and Nathan Fox, about the roles dogs played in World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War (grades 4+);

- Northwest Passage, by Scott Chantler(grades 4+);

- Boxers and Saints, by Gene Yang, about the Chinese Boxer rebellion (grades 5+).

Then here are science-related graphic novels (in addition to Feynman mentioned above) such as:

- XOC, by Matt Dembicki, about great white sharks and the Great Pacific Garbage Patch;

- I’m Not a Plastic Bag, by Rachel Hope-Allison, also about the great pacific garbage patch (all ages);

- Squish, by Jennifer and Matthew Holm, about what life is like for single-celled organism “kids” (grades 2+).

And these suggestions are just non-fiction and historical fiction. When you add in some truly outstanding fiction stories, there is just so much that a teacher can do and so many options and pairings to chose from.

Can you articulate why graphic novels are useful, or even better than text-only works, for each of those uses?

Aside from addressing Common Core Standards (as mentioned above), graphic novels are excellent classroom tools because they are wonderfully engaging, they carry a “cool” factor encouraging all kinds of readers, and while they are outstanding learning tools on their own, they can be used in all classrooms as motivators used to introduce often complicated and text-laden concepts. I love them because they “hook” the students. The kids think, “Oooh this is going to be fun!” or “OOOh this is going to be so easy…” and they let go of anxieties and dive in while being excited and having fun.

But not only can, and should, graphic novels be read in and out of classrooms, they should be written by students as well. Having students write their own graphic novels requires them break down their concepts into readable, flowing chunks while using succinct language. This helps with language use, comprehension, critical thinking and sequential processing. In today’s world of short Tweets, texts and messaging, and in today’s world where anyone can “report” “news,” we have to teach our students how to critically evaluate what they see, read, and write over the internet. Graphic novels are a wonderful bridge to teach these critical skills. In my visual literacy course, I teach students how visual and verbal messages can be used as rhetoric to ‘persuade’ audiences with minimal effort. Learning how image, color, font, and text can be used to relay obvious and hidden messages, is a powerful lesson they will use throughout their lives.

Finally, graphic novels can be used to help students develop crucial learning skills such as focused attention, memory, sequential processing, language usage and development, and critical thinking. Here’s how:

- Attention and attention to detail: Reading and integrating text and illustrations in graphic novels requires that students slow down a bit as they read. They have to both decode the text as well as integrate the information presented in the panel design and its detailed images. It requires attention to details. Furthermore, the short bursts of text empower students who have weak attention skills to focus on essential language messages while the images help hold and maintain their focus.

- Memory: Graphic novels pair visual and verbal storylines, creating additional memory pathways and associations. When you pair graphic novels with other text and digital resources, this only adds memory associations. Furthermore, research shows that our brain processes and stores visual information faster and more efficiently than it does verbal information. As a result, incorporating graphic novels into the curriculum and pairing them with traditional prose texts is an excellent means of promoting verbal skills and memory.

- Sequencing skills: Graphic novel panels and their sequential arrangement on a page and across the story visually and verbally break the story into recognizable parts. Readers must focus on their sequence, reinforcing concepts of beginning, middle, and end. Furthermore, with graphic novels, students can easily chart development of story, character, plot, and themes over time.

- Language and language usage: Graphic novels appeal to all language learners and readers. The concise text highlights word usage and vocabulary (as do the fonts used). The visual component then helps define, highlight, and reinforce vocabulary. Finally, as mentioned above, as the amount of text is more limited, weak language learners often feel more empowered in the classroom, and more at ease reading and participating in class.

- Critical thinking: Graphic novels reinforce critical thinking in a number of ways. Abstract concepts such as inference, metaphor, and social context are often difficult concepts for kids to comprehend. The images help make the concepts more concrete and less abstract. The sequential presentation of the panels also provide natural opportunities for scaffolding while the gutters offer natural breaks in which readers can pause to evaluate what they just read, making sure they comprehend language, story details, and character motives. The gutters and breaks also represent small gaps in the story (sometimes they are gaps in time, other times, actual story gaps), requiring readers to extrapolate and infer what is missing. Finally, metaphors permeate graphic novels. The visual and verbal paring make such metaphors more obvious, more concrete, easier to understand, and more relatable.

What advice can you give teachers and school librarians to help choose graphic novels that are appropriate for their classes?

The best way to choose graphic novels is to read them. You know your kids, your goals and your school culture and curricular expectations. As a result, you will know what will work best with your given parameters. That said, as a classroom teacher I know there are so many demands placed on teachers that reading and searching for resources can be challenging, if not downright impossible. So here are some outstanding resources to help make selections:

- Ask your school/local librarian for suggestions. He or she know not only what is age appropriate but what is popular and well-read.

- The American Library Association has a list of “The Best Graphic Novels for Children” with graphic novel suggestions for Grades K-2; Grades 3-5; and Grades 6-8

- A Parent’s Guide to the Best Kids’ Comics, by Scott Robins and Snow Wildsmith, contains 256 pages of reviews of kids’ comics and graphic novels. Each entry contains an overview of its suitability for kids along with enough information to help adults determine its appropriateness for their child/student.

- The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund has an ongoing column (through the generous contribution of the Gaiman Foundation) “Using Graphic Novels in Education,” which highlights a specific graphic novel or graphic novel series and how it can be incorporated into classrooms (including teaching suggestions and how they meet Common Core Standards)

- The School Library Journal is an excellent site with reviews and discussions about graphic novels and classroom use which can be found here and here.

- There are also books for teachers on how to integrate graphic novels into classrooms. Most that I’ve seen contain rationale for teaching with graphic novels, some sample lesson plans but little additional reading suggestions. The two books below have lesson plans along with extensive bibliographies and further title suggestions for middle and elementary school readers:

- Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning: a Guide for Middle-Level Educators, by Meryl Jaffe and Katie Monnin (2012, Maupin House), has graphic novel lesson plans and reading suggestions for middle school language arts, math, social studies and science classrooms.

- Teaching Early Reader Comics and Graphic Novels, by Katie Monnin (2011), explains graphic novels and provides lesson plans and reading suggestions for elementary-level language arts.

- Diamond Book Distributors has a list of graphic novels they distribute relaying how they fit into the Common Core Standards.

- http://departingthetext.blogspot.com/2012/09/he-yes-graphic-novels-should-be-used-to.html and – http://departingthetext.blogspot.com/2012/07/common-core-standards-and-changes-what.html are two posts on how graphic novels address Common Core Standards along with reading suggestions

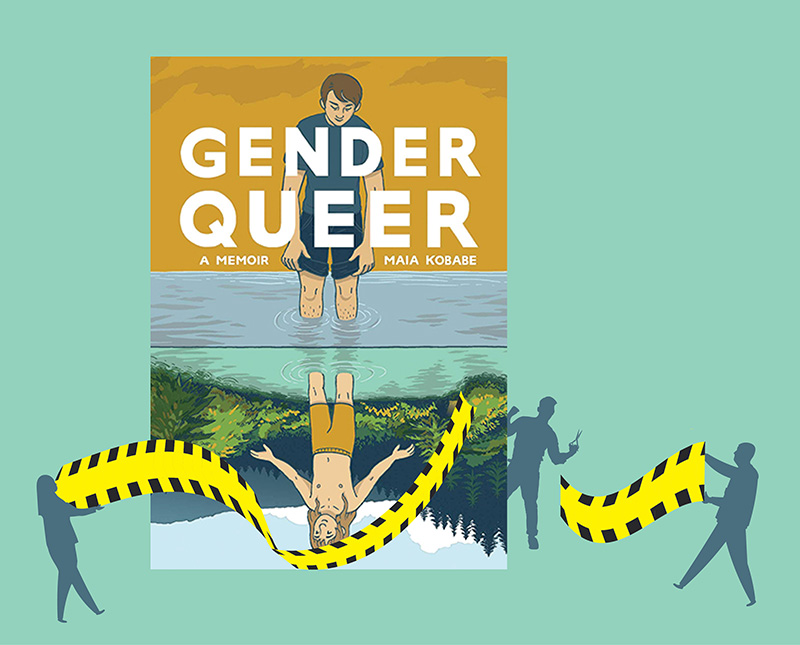

Are there steps educators and librarians can take to avoid challenges or to help them respond to challenges if they do happen?

Great question. There are a few things teachers and librarians can do to avoid challenges:

- Read through the comic or graphic novel before using it. As you know the school/library/community culture, demands and expectations you will have a sense of what is appropriate.

- Charles Brownstein, Executive Director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, always cites the need for having strong policies and guidelines in place. Such established policies and guidelines make it easier to tackle challenges that might arise.

- Be prepared. Head off challenges with research and resources Be able to show the values of graphic novels. You may also want to search the title of the graphic novel your’re hoping to use. See if it has been challenged and why. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) has some outstanding resources to help:

- An ongoing column, “Using Graphic Novels in Education,” highlights selected specific graphic novel or graphic novel series (one to two columns are published per month). For each book highlighted, there is a summary, a list of the book’s themes, suggested lessons and discussions, suggested paired readings, and additional resources you might want to incorporate in your lessons. Each posting also discusses how the teaching suggestions meet Common Core Standards.

- Raising a Reader: How Comics and Graphic Novels Can Help Your Kids Love to Read! by Meryl Jaffe, with art by Raina Telgemeier and Matthew Holm, and an introduction by Jennifer Holm (sponsored by the Gaiman Foundation). This publication relates WHY graphic novels are great classroom additions. So if you’re about to head to a department/administrative/board meeting where the use of graphic novels in general is questioned, this is a great resource to share. It can be downloaded for free from the link above.

- Graphic Novels: Suggestions for Librarians, with title and shelving suggestions

- CBLDF Banned Books Week Handbook, with art by Jeff Smith can be downloaded here for free http://cbldf.org/2014/06/celebrate-the-freedom-to-read-with-cbldfs-new-banned-books-week-handbook/

- For those interested in Manga, CBLDF and Dark Horse published CBLDF Presents Manga: Introduction, Challenges, and Best Practices.

- You can also go to CBLDF at cbldf.org and under “Search” type in the book(s) you are hoping to use. You will then see if, when, where, and why that particular publication was challenged.

Are age ratings given by publishers helpful? Are they consistent enough?

For some time the Comics Code Authority required the rating of comics and graphic novels. With the disbanding of the Comics Code Authority, age-appropriate guidelines are now determined by the individual publishers for their publications.

In truth, I wrestle with the issue of ratings. I often tell a story about my own daughter. She was and continues to be an avid reader, and as a child I couldn’t keep up with her pace. She’d gone through my recommendations and still wanted more. So I suggested Newberry Award winners, knowing that they were “quality” books. One such book she picked up was Julie of the Wolves. She read this when she was in third grade and when I asked her what she thought of it she said she liked it but she didn’t quite understand why one boy who liked Julie jumped on her and scared her. (She was raped.) I was not prepared to have this discussion, although clearly it needed to be had.

As a parent, I would have loved for all my kids’ books to be rated. It would have made things simpler. But again, as a parent and a teacher I know that we all have our own tolerances for violence and language content, which makes ratings more problematic.

While I know most parents and teachers can’t read each book they recommend to a child, ratings and tolerance for language and violence are to a certain extent, subjective—hence my problem. So I find, once again, the best advice I can give when asked, is to either read through the book before assigning or recommending it, or search reliable sources such as those listed above for reviews and suggestions of appropriateness. Some additional resources:

Scholastic has a booklet, Using Graphic Novels with Children and Teens: A Guide for Teachers and Librarians. It relays why graphic novels work so well in classrooms, and presents their graphic novel collection along with additional graphic novel resources.

Graphic Novels, Comics, and the Common Core: Using Graphic Novels Across the Elementary Curriculum, by Karen Gavigan and Sue Kimmel for ALA – American Association of School Librarians’ Conference 2013. This is a PDF for their presentation which contains graphic novel award winners and curriculum connections.

Another book with high school teaching suggestions for graphic novels is: The Graphic Novel Classroom: POWerful Teaching and Learning with Images, by Maureen Bakis.

One thing I’m interested in is the trend line. When did graphic novels start catching your attention? It seems like there weren’t a lot before the late 90s. My own subjective impression is that there was a surge in interest in using graphic novels for education in the early to mid 2000s and then it died down a bit. Have you seen a change? Is there less interest, or is it just that it’s not such a novelty any more—or am I just wrong about that?

Ha, you got me here! Now I have to confess. I used to be the parent and teacher who said, “Don’t even think of bringing that stuff into my home/classroom!” I teach language arts to gifted and talented students (grades 1-8) and believed in teaching the classics. In my opinion all comics were like Archie and assorted superheroes I grew up with and, in my opinion, didn’t belong in the classroom. It wasn’t until my kids were a bit older (middle school and high school – about 5 years ago) when they did an intervention with me. They sat me down and told me that if I really was a literacy specialist (I was at this time out of the traditional classroom giving teacher workshops and consulting with public and private schools near our home), I needed to take a closer look at comics. They weren’t what I thought they were.

In all fairness, I grew up in the 1970s, and the comics available were limited. I told them I’d accept their challenge – but on my conditions. Recommend one graphic novel and let me make my own decision. They gave me Joe Kelly’s I Kill Giants (about 5th grader Barbara who claims she kills giants and has no patience for much else). I was blown away. This book, aside from its powerful story, was all about metaphor. What an awesome classroom tool!

I now advocate for graphic novels in the classroom, teach courses on critical reading and visual literacy, and love, love, love the outstanding resources and graphic novels available for readers of all ages.

From my perspective, teaching and reviewing graphic novels, they just seem to get better. There are so many more serious works that are classics in their own right. Their art, overall design and language use are only improving in quality. I don’t see less interest, but I’ve only been on board for the last five years, and I am dealing with teachers, parents and school boards. From my perspective, there is still a learning/acceptance curve graphic novels must make with parents and teachers. In fact, at teacher conferences I see a growing interest in incorporating them into lessons. Librarians, however, have been advocating for these books for a much longer time and with librarians, the learning curve may have already been established.

Aside from a bad rep graphic novels have had to fight, the major bookstores don’t carry many of these outstanding works and so parents and teachers are more limited in ‘discovering’ them. While the major book chains carry Babymouse, Squish, Amulet, Lunch Lady, Smile, Amelia Rules, and a few other series, there is so much many outstanding works that aren’t shelved. Here too, a lot of the responsibility falls on librarians.

Also, do you see any connection between the advocacy by public librarians for graphic novels (including them in collections, regarding them as literature) and their adoption in education? Are the two connected?

They are absolutely connected. Librarians have known for quite some time that graphic novels get kids into libraries and gets them reading! They’ve known for quite some time what titles, authors and publishers the kids love and they are the ones empowering teachers and educators. It is the librarians on ‘the front’ who have made my job so much easier. In my experience there is a direct correlation, and we owe librarians a great deal for their advocacy.

Filed under: Interviews

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT

Happy to be included among so many good books, but I assure you that NORTHWEST PASSAGE is fiction (and, being set here in Canada, not an American anything). It’s a common mistake, and I take it as a compliment that so many people think my frontier adventure tale is a real story from history. But describing it as non-fiction is, alas, inaccurate.

Thanks for your comment, Scott! I’ll move it to the Fiction list, but I regard Canada as part of America, just as the United States and Mexico are!

Thank you, Scott. I bow to Brigid’s response (I always think of the New Yorker Magazine’s New Yorker’s View of the World poster). Fiction or historical fiction, yours is an outstanding book and resource. Thank you.