Paul Bunyan: The Invention of an American Legend | Review

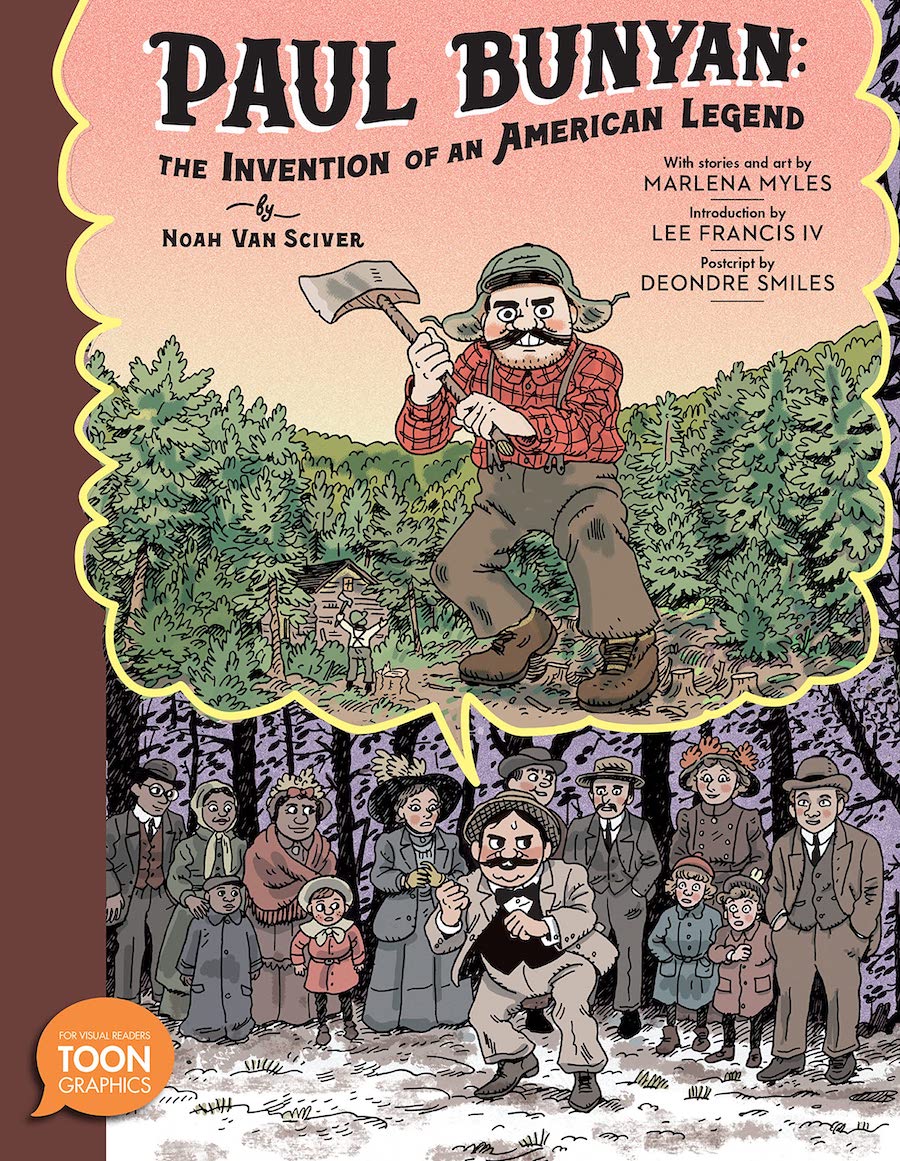

Paul Bunyan: The Invention of an American Legend

Writer/artist: Noah Van Sciver

Toon Books; $17.99

Gr 3 Up

Everyone knows Paul Bunyan. An organic myth born of the tall tales told in lumber camps, the legendary lumberjack was a giant who, along with his pet Babe the Blue Ox, was responsible for prodigious acts of forest-clearing, pancake consumption, and even for the very geography of the United States, right?

Not quite…and, as it turns out, the American “folk hero” had a dark side to him, a shadow that comes with being the creation of an advertising man apologizing for the logging industry. Readers will meet both Paul Bunyans in cartoonist Noah Van Sciver’s new Toon Books comic, Paul Bunyan: The Invention of an American Legend.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

As with most Toon Books, there is a great deal of information packed on either end of the comic story, providing necessary context. In this case, that means an introduction by Lee Francis IV, which explains that the Paul Bunyan many Americans now primarily through a 1958 Disney cartoon is actually the invention of ad man William B. Laughead that he says was “manufactured to help promote the timber industry,” but also to explain the colonialist impulse to settle the lands that already belonged to indigenous people for so-called “American civilization.”

The story is then followed by a short essay by Dr. Deondre Smiles about historical American deforestation, a few short features written and illustrated by Marlena Myes about the tree-dwelling little people of Native American legend, a map of the Dakota homelands, and some important plants and trees in indigenous medicine.

All of this helps contextualize the story of Paul Bunyan with native voices—indeed, all of the contributors to the supporting matter are of indigenous descent—that are otherwise always missing from the story and conspicuous in their absence, essentially starting a cycle of American creation myths with the arrival of a big white man into the “wild” native forests.

As for the main event, Van Sciver’s story, it opens on a train running through Minnesota in the winter of 1914. A businessman in a suit and puffing on a cigar is explaining to his seatmate how he’s a timber industry man—perhaps not Laughead himself, but a credible stand-in—and how he grew up in the camps before becoming advertising manager.

“Ach!” replies his seatmate. “The industry let us down. I gave them the best years of my life as a timber cruiser–but look; now that all the old growth has been cut, you folks are just moving west.”

The train then comes to an unexpected stop due to a blockage on the tracks, and many of the passengers take the opportunity to spill outside into the snow. A fire is soon built, and when someone asks if anyone has any stories, the ad man’s seatmate volunteers that he’s spent his life around a fire in logging camps, “so you’ve bet I’ve got stories!” He tells the story of a legendary lumberjack. That’s followed by several others sharing their own stories of big, tough lumberjacks. The ad man breaks in, saying all of those just mentioned are nothing but “small fry compared to Paul Bunyan, the greatest lumberjack of them all.” He then launches into the life story of the tall-tale hero, who, in a clever move, Van Sciver draws to resemble a bigger, stronger, younger, more square-jawed version of the ad man himself.

He gets through Bunyan’s childhood and beginning career as a lumberjack before the seatmate cuts in for the first time: “I know all of the greatest lumberjacks, and I never heard of him.” With the crowds’ encouragement, the ad man continues, telling how Paul Bunyan created the Finger Lakes, how he met Babe, how they created the 10,000 lakes of Minnesota, how they straightened an exceptionally crooked road, their love of flapjacks and so on.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The tales seem to enchant, but they don’t go unchallenged, as the seatmate scoffs and phooeys not only the bigger-than-life acts of Paul Bunyan but, nearing the climax, the timber industry’s treatment of the forests themselves.

Back on the train, after all the amusing stories are told, the seatmate is joined by a train employee, who notes he has seen the forest vanishing through the train windows over the past twenty years. In private, they castigate the ad man for all the sins of the timber industry, and, in the powerful last lines, when all the ad man’s bluster has disappeared and the truth has gone (acknowledged by the look Van Sciver draws on his face), the seatmate says, ” I hear that California is very beautiful. And I hope that one day I get to see it before your Paul Bunyan gets to lay waste to it.”

The book is then at once a celebration of the way the industry sold itself and a castigation of the way it behaved, a rollicking recounting of the tall tales—perhaps more cynically invented than we usually think—that nevertheless is clear-headed about what, exactly, is being celebrated in them.

Logging culture may have produced some great stories. But it also cost America, and especially the indigenous people whose land all those trees once stood on, greatly. Both facts are important parts of our history. Van Sciver’s Paul Bunyan tells them both, and he does so in a way that is both potent and fun.

Filed under: Reviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Should I make it holographic? Let’s make it holographic: a JUST ONE WAVE preorder gift for you

Press Release Fun: Happy Inaugural We Need Diverse Books Day!

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

RA Tool of the Week: Inside Out Inspired Emotions, but Make it YA Books

ADVERTISEMENT