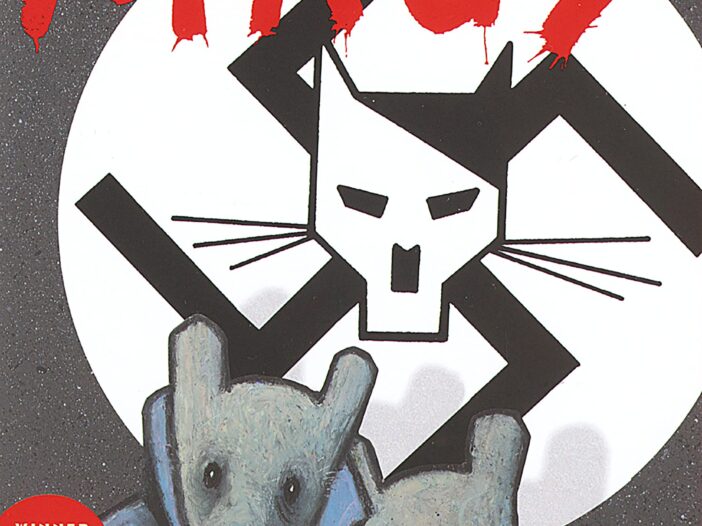

Maus and Other Graphic Novel Challenges | Roundtable

On January 27th, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the news broke that in Tennessee a School Board unanimously voted to remove Art Spiegelman’s Maus from the 8th-grade curriculum. This is just the latest of many censorship attempts throughout the country to remove books from school and public libraries as well as classrooms because they discuss sexuality or institutional racism.

In this case, Maus has not been removed from libraries but removed from the eighth-grade curriculum, where it was the centerpiece of a social studies unit about the Holocaust. But the reasons for its removal have many people raising their brows. Nudity? Profane language? Middle school kids are notorious for their potty mouths. Students who regularly watch TV and movies and play video games are exposed to violence, foul language, and worse. Yet the School Board members felt that teaching about the Holocaust using this text was not appropriate.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Maus is a Pulitzer Prize-winning title that depicts the relationship between father and son as they share the father’s experiences in the Holocaust during World War II. It is an honest and realistic portrayal of the events.

Here at Good Comics for Kids, we started to discuss the events as they unfold and the broader question of the wave of book challenges that is happening throughout the country. I am a middle school librarian in New York City, Robin Brenner is a teen services librarian in Brookline, Massachusetts, and Mike Pawuk is a teen services librarian at the Cuyahoga County Public Library in Brooklyn, Ohio.

In your opinion, is this censorship? The book has not been removed from libraries and is still available for students to read on their own.

Robin: Yes, in this case, this move is a kind of censorship because the procedures in place for evaluating and considering texts for the school were ignored and overridden by the school board. The expertise of the teachers involved, who had built a complete curriculum around teaching Maus, has been dismissed outright. The discussion and questions led by teachers in a classroom setting would benefit students greatly in reading Maus, a notably complex work. I believe that if the teachers who work within the community believe that their grade 8 students can tackle Maus, then they should be supported in that decision.

Also, I don’t believe it’s helpful to get mired in the semantics of defining censorship or banning. Challenges that are happening across the country right now represent a wider trend of restricting access, and that’s what’s most troubling to me.

Mike: I have mixed feelings about this. As a teen librarian for over 25 years and a lifelong supporter of the medium, I personally don’t think the book is appropriate for 8th graders. The original audience for the book when it was originally published in Raw was never for middle schoolers, but adults. In my library system, Maus has been shelved in the Adult collection for decades. I have no problem with this being used by high schools. And it should be noted that the title isn’t banned either as it’s been misreported by sources including PBS and USA Today – just removed from the curriculum. The school board did not discuss banning the book from school premises, discouraging students from reading it, or even removing it from school libraries.

Esther: Mike, I agree that Maus was not written for children or even teens. But many books that are written for adults have teen interests. That’s why YALSA created the Alex award, to recognize adult novels that teens could or would appreciate. So while this isn’t a kid’s book, the material can be read by even young teens. Many moons ago, I had a team of 8th-grade teachers who chose to teach Maus. It was well received by the teachers (who did not stay on the 8th-grade team which is part of the reason it did not stay in the curriculum) and by the students. I am very concerned that politicians and not professionals are making the decisions about what is and is not being taught in schools.

Reading through the school board minutes, I was left scratching my head. I understand that I have lived most of my life in NYC which is more urban than McMinn County, but the reasons that were given by the board to take the book out of the curriculum defy any sound educational logic. Just because a student reads a bad word does not mean they will use it. And let’s be real, they will hear those words at home, on the street, and on TV. Honestly, I have to wonder what made the Board members so uncomfortable.

I understand all that, but being in the schools, educators and stuff we don’t need to enable or somewhat promote this stuff. It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy.

This particular quote blew my mind and honestly had me seeing red. The point of reading Maus, the point of teaching this generation of the atrocities, like killing kids and people hanging, is so that a mass murder like this never happens again. The Board member equated the violence of the Holocaust with what children see on TV. And therein lies the wrongness of this matter.

In addition, what better choice to teach about this topic that would be accessible to students? This is something we’re grappling with on our 8th grade ELA team. Night is just as difficult as Maus, but possibly less “graphic.” We were trying to find a text that was accessible to a broad range of students and be hard-hitting. We wanted to move away from the story of Anne Frank, which shares a limited view of what happened during the Holocaust. So by limiting the educators, I feel like they are limiting the teaching of this very important topic. So to answer the original question, I do think it’s censorship, even if students have access to the book.

Mike: That’s a good point, Esther. I myself didn’t really study the horrendous atrocities of World War II and the Holocaust until I was most likely in 10th or 11th grade in the more brutal details. We watched horrendous videos of the Holocaust as part of the discussion that still disturbs me today that defies description. I know schools discuss the topic at varying grades and there’s always a need for materials to help accompany the subject matter and it can be very limiting what is beyond the story of Anne Frank. There also will always be a subjective point of what defines a “mature” reader who is able to understand more adult fiction/material. I know there are passionate comic book fans who devoured Maus at 13 and were changed forever as readers. Some of the staff here were in 9th grade when they first read it. You can be a voracious reader of materials in 7th grade or a very limited reader in 11th grade. I do think that there’s still a push for some graphic material to be used in an educational setting that may be meant for older readers but some educators may use it because it’s “just a comic book.”

Robin: It’s a particularly complicated history to talk about, especially with younger readers, and yes, I read Maus when I was in grade 9 as part of the Facing History and Ourselves curriculum at the time. It had a great impact on me, but I am just one person, and I agree it’s always a balance between what works for one reader versus an entire class or an entire school.

Esther: Robin, you make a great point, that there is no easy way to teach the Holocaust. My 6th graders are reading White Bird by R.J. Palacio and They Called Us Enemy by George Takei. They came to the library for some extension activities which include Jack Daw photo collections. I was walking a group of kids through the photos explaining some of the pictures, and I was editing myself, trying not to get too graphic or too explicit. But the point is: The Nazis did not make this easy and I have students who cannot even tell me about the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States which is only 20 years in the past. The Holocaust is nearly 80 years in the past, and survivors are few at this point.

What about the broader question of censorship in schools and libraries? Graphic novels seem to be easy targets because the visuals pop out.

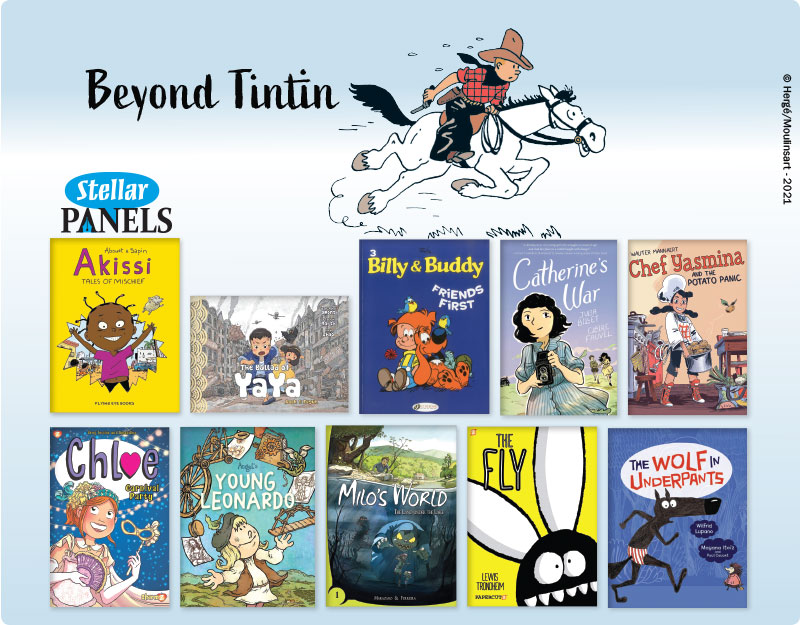

Robin: To be fair, this is not new in the sense that graphic novels are frequently targets for challenges because of their visual nature. Some of the fear of these titles seems rooted in the very fact that comics and graphic novels are so engaging for young readers. Our society still holds the overarching belief that seeing something in images will have a more immediate, lasting impact than reading the same thing described with words. As examined over at Book Riot by Danika Ellis, graphic novels are included in the 850 title list sent by Texas Republican State Representative Matt Krause to the Texas Education Agency, which has become a go-to list for submitting challenges to titles in local schools and library collections. As Ellis’s breakdown shows, these graphic novels are being challenged most frequently due to their inclusion of BIPOC and queer lives and characters, but no doubt panels from these pages are being shared out of context to inflame arguments.

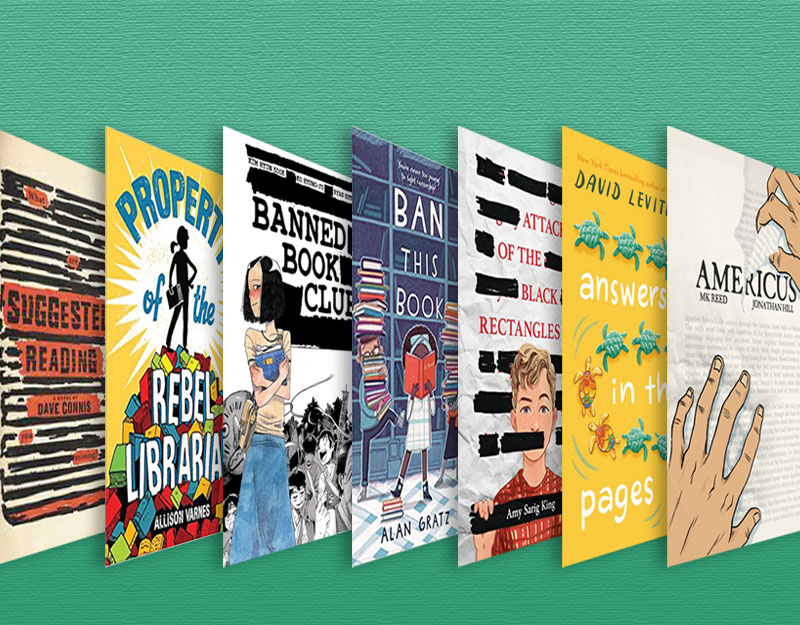

Graphic novels are being included at a significant rate in this wave – starting with Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer and more recently including younger titles like Raina Telgemeier’s Drama. In coverage of the ongoing struggle between new Library Board members and library staff of the ImagineIF Library in Flathead County, Montana, two new Library Board members debated, in reaction to a challenge to Gender Queer, “…a suggestion to remove all graphic novels as a genre category, as ‘Gender Queer’ is a graphic novel, asking whether other graphic novels in the collection are ‘infantile’ or ‘vulgar.'” On February 2, NBC News shared a list of the 50 most challenged titles in schools in Texas, and 10 of the 50 are graphic novels, with 9 of the 10 titles created for younger readers. This list also includes White Bird, the R. J. Palacio graphic novel that also focuses on the horrors of the Holocaust and could be considered an alternative to Maus – but if they all get challenged, what are educators and librarians to do?

Mike: I agree with Robin in that the visual nature of comic books will always make them an easier target by people who seek to find something easy to object to. Comics’ sibling, film, has that same issue, but we’re used to the Motion Picture Association having content ratings for feature films but graphic novels may not always have a rating associated with the titles. To play devil’s advocate, if Maus was adapted into a feature film, Maus would naturally have an R-rating. Would it be appropriate for a middle school to show a rated R movie such as Schindler’s List in the classroom? Probably not. Can Maus be used as an excellent education tool for schools? Without a doubt. There’s a reason why the book has been a fixture in adult comics since it was published starting in 1980. My concern is that the material in the book is definitely of a mature nature and would be better suited for an older high school audience or older who has a better grasp of the significance of history and experience behind them in order to fully understand what’s happening in the book.

As for the overall concern of books being censored or banned, I think we’re always going to have a disagreement on what’s an “appropriate” title to have in a library setting, particularly when it comes to more left or right-leaning material. Libraries are a repository for all ideas – not just one point of view but they are also a reflection of our communities too. It used to be said of libraries “If we don’t have something that offends you, then we’re not doing our job.” I still stand by that, but you will always find some communities are more liberal and more tolerant of material that appeals to that audience and the opposite can be said as well for conservative-leaning communities. A Seattle school is removing To Kill a Mockingbird from its 9th-grade curriculum due to it being considered racially insensitive, so this is nothing new having schools revising their curriculum.

As a public librarian, there’s a little more flexibility in that we can carry materials that suit the needs of our diverse communities. I have a lot of material in my collection that I don’t care for personally and can be considered agenda-driven by some, but wouldn’t think of restricting access to it. For example, I’d had a lot of manga-reading friends rave about Boys Love manga. I love manga, but I don’t care for Boys Love manga. We carry it in my public library in our teen collection and it doesn’t deserve to be removed just because I don’t care to read it. Again as evident from the passion on this topic – I want to remind everyone that no one is being restricted from reading Maus. If you want to read it? Go for it. No one is telling the kids not to.

We all love reading and we all love graphic novels and the power of the comic book and how it connects with that right reader or else we wouldn’t all be up in arms right now about Maus regardless of whether or not we think it’s appropriate for middle schoolers or not. We all at the end of the day thrive on connecting the right book in the hands of a reader. There’s no better feeling than that as a librarian.

Robin: Of course, some members of communities may object to different titles for a wide range of reasons, but the collection development policies and procedures for title reconsideration are being skipped. The issue with this decision around Maus is that it isn’t a revision of the curriculum. As Esther said above, authorities who have no expertise in the work are overruling trained educators. The removal of To Kill a Mockingbird included input from students and educators and left the door open for teachers to use the text in their coursework to give it context. These current calls for removals don’t allow any such nuance or understanding of teaching and instead aim to eliminate carefully selected titles over vociferous objections.

Authorities are also removing titles that are overwhelmingly by BIPOC and/or queer creators showing BIPOC and/or queer lives claiming that they are inappropriate for young readers. This telegraphs a rejection of whole categories of people who, yes, exist in every community and in the greater world. I’ve spent my entire career as a teen librarian advocating for the varied teens that come into my room every day, and I will continue to ensure we have titles that represent all of them (and beyond!) on my shelves.

What can libraries and schools do to help stop this large oversight?

Robin: As a public librarian, I’ve been trying to listen to school librarians and educators about what anyone can do to be helpful (and to take note of what is, while well-meaning, not helpful.) As relating to Maus, the recent trend of buying and mailing copies of challenged titles to the libraries and institutions coping with these issues may seem like a good idea but is often not actually helpful due to the library’s inability to accept or process those donations. However, writing letters to library administrators, running for local office including school boards, and showing up to speak at local civic meetings are all excellent ways to make sure your voice is heard. As someone who was inspired to write to my local elected officials (for the first time) in the past two years to defend my local library, I can attest that it’s worth it.

I keep track of which libraries are establishing official fundraising requests through organizations like EveryLibrary’s Rapid Action Fund. Once again over at Book Riot, Kelly Jensen has written up an excellent Anti-Censorship Toolkit that addresses both what citizens can do as well as what we librarians can do. The ALA’s Graphic Novels and Comics Round Table (GNCRT) has formed a new committee to work on addressing challenges specifically to graphic novels and comics and providing support and resources to library staff. From the announcement, “This committee will operate from January 2022 to June 2022 and is tasked with developing and delivering a guide on preparing for and addressing these challenges,” so I look forward to being able to point folks to that resource soon. GNCRT member and Chair of the Addressing Challenges Committee Amie Wright also has a Trade Secrets column in the February 2022 issue of Booklist, Facing Challenges to Comics, which offers sound advice.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Esther: I don’t know what can stop this trend, but I do think it’s important that libraries have a very clear selection policy. It’s been years since a book in my collection was challenged, but a clear policy to refer to and procedures for reconsideration are important. And frankly, that should be for curriculum in schools too.

Robin: Esther, I agree that having a clear and strong collection development policy is very important, but I fear what’s happening now is that folks are going around the policies in place and outright ignoring the set procedures. That’s worrying, to be sure! Do you know, as a school librarian, is there a similar sort of mission statement for curriculums in schools, classes, or departments?

Esther: Robin, you make a great point. I couldn’t think of any specific policy that we have in NYC and tried to dig around. Interesting, I found a site from California that is a guide to selection lists. I know that NYCSLS has been working on lists for classroom libraries and they are using their selection policy for the most part, but it has to look different because a classroom collection isn’t the same as a library collection. It’s true that a solid collection policy and curriculum criteria aren’t going to solve all the problems, but it’s a start.

I think parents and politicians have to remember that public settings such as public education and public libraries are not a one-size-fits-all option. Like Mike said about public libraries: It’s a repository for all ideas and they don’t align with each person’s core values. But rather public settings try to capture everyone’s core values. Therefore, if you are sending your children to the public library there will be books that could offend your core beliefs, and if you send your children to public schools, it’s likely things will be taught that also don’t align with your core beliefs. It’s our job as parents to anchor our children and tell them how we feel and then hope that when they fly free they will go in the path we set for them. I struggle with this in my own life and work hard not to impose my own beliefs in my job or in the world around me. Right now, it feels like small groups of people are trying to impose their beliefs on a whole lot of people.

Related Reading:

What it’s Like to Be the Target of a Book Banning Effort

What Kids Lose When They Don’t Read Books Like ‘Maus‘

Resources:

Intellectual Freedom: Issues and Resources

Filed under: Roundtables

About Esther Keller

Esther Keller is the librarian at William E. Grady CTE HS in Brooklyn, NY. In addition, she curates the Graphic Novel collection for the NYC DOE Citywide Digital Library. She started her career at the Brooklyn Public Library and later jumped ship to the school system so she could have summer vacation and a job that would align with a growing family's schedule. On the side, she is a mother of 4 and regularly reviews for SLJ. In her past life, she served on the Great Graphic Novels for Teens Committee where she solidified her love and dedication to comics and worked in the same middle school library for 20 years.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT