Tell No Tales | Creator Interview

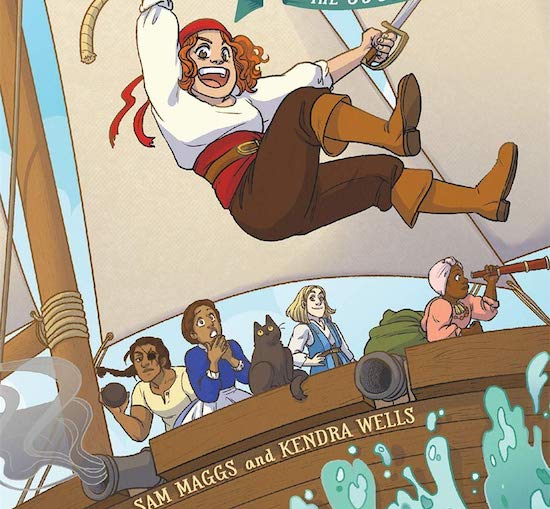

Tell No Tales, published last month by Abrams, is a pirate story for modern readers—in fact, writer Sam Maggs said she had her 13-year-old self in mind as she wrote it. In the story, Maggs and artist Kendra Wells re-imagine the lives of pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read, keeping all the swashbuckling but casting the protagonists as queer and nonbinary, adding in a diverse crew with stories of their own, and setting them all against a pirate-hating antagonist with a steampunk ship of his own. It’s a big, action-packed fantasy that takes place in a world that’s just as diverse as the world outside its pages. We talked to the creators of Tell No Tales about their first encounters with pirates, separating the real history from the legends, and how many of the most fantastical elements of this story are actually true to life.

How did you first encounter pirates, and how did that inspire this book?

Kendra: When I was in high school, we had to do a 15-page research paper as a final project. I had chosen to talk about Anne Bonny and Mary Read because I had a childhood fascination with pirates. I started reading about them and I was like, that’s so awesome that we have that record of female pirates doing their thing in the age of piracy and becoming so notorious. As I’ve grown up, I realized a lot of it was probably very sensationalized, but I’ve been familiar with the story of Anne Bonny and Mary Read for a long time.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Sam and I have been friends for years. I was on Twitter, and I was on a tear, talking about how is it possible that even after Pirates of the Caribbean and the show Black Sails, no one has done a real focused story on Anne Bonny and Mary Read specifically? And Sam jumped in and was like “Do you want to make a book about it?” And I was like, “Yeah!”

Sam: We all grow up with gendered ideas of what you can like, so I grew up thinking pirates were a boy thing until Pirates of the Caribbean came out, and I was obsessed with Keira Knightley—I wanted to be her and, I realized, also date her. A few years ago I was writing a nonfiction book about female friendships in history, and I wrote one of my chapters on Anne Bonny and Mary Read, so I did a bunch of research and separated the wheat from the chaff in terms of what was essentially real and what was sensationalized, and I thought even the real bits of her story were fascinating. So when I saw Kendra say on Twitter “I really want to do this,” I said “Oh my gosh, I really want to do this! I’ve already done the research. I am so ready to tackle this!”

Who did you have in mind as your audience?

Sam: For me it was me as a 13-year-old, essentially. My favorite fantasy books growing up were Tamora Pierce’s books, which were all about girls dressing up as knights and going on big fantasy adventures. Books like that made me want to be a writer, and [I thought] I would love to try to do a sort of graphic novel version of a grand adventure that as many of our readers could see themselves in as possible, because it was really transformative and meaningful for me to see. A fantasy book in the vein of Game of Thrones but with all these really strong women characters—and of course, Kendra is nonbinary. We know gender nonconforming people have always existed. We don’t see them so much in the historical record because of a lack of language for that in history, or a lack of historical records, so we want to reclaim some of that women’s and gender nonconforming history and put it back into the narrative.

In your book, Read is nonbinary. How did you come up with that?

Sam: I think it was Kendra’s suggestion. As we talked about the character it just seemed to make sense for us to have that representation in the book, and it seemed really organic for their character.

Kendra: Thinking back on it, I’m hard pressed to find the specific moments where we made those decisions. It all just kind of sprung out fully formed this way. All these characters were so crystallized from the beginning. It was never a choice where we were like well we had to have a nonbinary person, it wasn’t that conscious, it just made sense.

Sam: We have these people who are stretching out across the gender spectrum, defying the expectations of being a woman in the 18th century, which is pretty transgressive, so we have no reason to think that this wasn’t the case.

Kendra: It was fun to represent that in both Anne and Read. I think a lot of people who aren’t familiar with gender nonconforming people assume if you’re a woman and you don’t feel super feminine you can just wear pants, be a tomboy. It was nice to represent both Anne, who is very much a tomboy type character but very much a young woman, and Read who behaves sort of similarly to that, but the importance being that they identify as much.

When did you decide there was going to be an anachronistic steamboat in there?

Kendra: It’s not as anachronistic as people might think. The design was completely original and made to be very fantastical, but Sam sent over a lot of reference and a lot of notes. Basically it very much could have existed at least very close to the time period

Sam: We found the beginnings of a lot of this sort of steamship technology were starting to come about at this point, so if they had developed the technology at that time just a little bit further, if someone had the money and the wherewithal and maybe the desire or drive from potentially a bad place like this, what could they have created? And then Kendra spent a really, really long time doing a bunch of drafts of the ship to try to get the design exactly right, so it was both realistic and believable looking but also menacing, and it had that sort of fantasy element where if you looked at that you immediately knew it was scary. We talked a lot about FernGully—the oil monster in FernGully traumatized me as a child, and we kept talking about getting the vibe of that into a ship. I think Kendra really pulled it off

Kendra: Our thesis with this story is that pirates have been sensationalized over the years, and a lot of that is intentional. The British crown hated pirates. There were bad pirates—not all of them were super cool radical adventurers doing their own thing—but a lot of it was a propagandized campaign against them to turn the common people to see these people as criminals, as bootleggers and not good members of society. Part of making Woodes’s ship so fantastical was I wanted to bring in the mythology of it. Did this ship look like this? Did it behave this way? Could it actually move that fast? Or was that Anne’s recollection of how terrifying it was in the moment?

Sam: We do have that sort of unreliable narrator element in this book, where Anne is telling this story you don’t necessarily know if it’s the truth or not

Kendra: Was there a vision, was there magic, or a was it just a couple of very smart young people getting out of a tough situation?

Sam: It helps to remember the historical context in which pirates existed, which was 50-60 years before the American Revolution. People in the colonies are restless. They are desperate for more freedom for self-governance. People are being pressed into the British Navy ships for low pay, with no disability insurance, nothing for them back home with their families, and only white men were allowed to do this. Piracy offered a very different life where captains were elected democratically, everyone was provided with disability and death insurance, and they welcomed escaped slaves, women, all kinds of people of color. They were a very folk-hero, Robin Hood-esque group of characters that the colonies were so drawn to that the British and Spanish empires had to wage a disinformation campaign against them to make them seem a lot more evil than they were. Pirates were very threatening to the established social order. We see a lot of that today, people trying to unionize, trying to stand up and be paid what they are worth for their work, people are fighting for racial equality and gender equality still, and I don’t want to say Woodes is Jeff Bezos but maybe Woodes is Bezos, he’s a very establishment character that you still rail against today. Necessarily.

A lot of times with a book like this the artist likes to put in every detail of the ships and the setting. You chose not to do this. Why did you decide on this level of detail, and what visual references were you working from?

Kendra: The visual records are pretty limited because you are dealing with a lot of engravings, woodcut art, art that was expensive to reproduce and to create at all, and it was primarily done by people who were more involved with the British side of things, so it’s hard to get a lot of first-hand reference for this kind of stuff. I wanted this book to be lush and engaging and emotionally driven, and pirate ships are really hard to draw, so I needed to be aware of the amount that I could put in without things getting over complicated. I was trying to balance wanting to have as much detail as made the story clear without losing sight of what is really important. A friend of mine who is a pirate ship enthusiast pointed out even at the time pirate ships weren’t built the same way every time. A lot of the time the ropes were just thrown around wherever they needed to be. There wasn’t a lot of science behind every single rope and pulley, so I wanted to get across the gist of it without losing sight of what was important in the story.

It’s a diverse crew, and you both are white. How did you feel about bringing in people of color? Did you have sensitivity readers or did you consult with people of color about that piece of it?

Sam: Yes, we did. For us, it’s obviously very important to represent the world as it exists around us. I am queer and Kendra is nonbinary, so we have some great self-resources for filling gaps with our own voices, but it’s obviously irresponsible of us to not include any people of color in the book. We don’t want to tell a person of color’s story, so it’s great this takes place from Anne’s perspective, but pirates came from all walks of life, so it was more authentic to include characters of color than to not include them. We wrote all these characters, then we did bring on some sensitivity readers once the script was in place to take a look at our indigenous character and our Black character and our half-Black character to make sure we had not made any missteps and had treated these characters respectfully and as real, fleshed-out human people.

Kendra: Anne and Read are the primary protagonists, but we didn’t want it to read it as The Anne and Read Show with a supporting cast of people who are only there to lead them on their journey. It was really important to have each of these characters have their own motivations and their own lives and their own journeys they were on, their own goals. They are friends, they are crew mates, they are all supporting each other, but they all also needed to be their own people.

Why aren’t the pirates flying the Jolly Roger?

Sam: The Jolly Roger is not historically accurate. That is a creation that we have seen come into play in our public pop culture awareness over the years. The Jolly Roger is not a thing that really happened, although some pirates did have either their own pirate flags or they would fly a skeleton flag, which is where the Jolly Roger comes from.

Kendra: There is a small Easter egg in the very first scene: When Anne wakes up in her cabin, she has a flag hanging on the wall with a skull and two crossed sabers. That is actually historically Calico Jack’s flag. It’s kind of like an homage—she probably stole it from Jack. For their own flag, we settled on a very long, red pigtail. Anne has her signature red bandanna on basically the entire book, and I wanted something with her red hair, and it suited them really well without being super flashy. It’s a lot easier to get a bolt of red fabric than design a whole flag, I assume.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

You make the point a lot that pirates had a lot of freedom that ordinary people didn’t. Do you feel that was important for people to know that were reading the book?

Kendra: Stories are told by the winners, and the British ultimately ended up wiping out piracy pretty well, so you don’t get a lot of these sympathetic tales of piracy and of the kind of people who would be operating these ships and the reasons why they would be doing it. The character Sara is the mixed child of a wealthy landowner. She could live a very comfortable life and study medicine and be handed pretty much whatever she would want, but she wants more than that, and she finds that with Anne. She and Anne butt heads a lot and don’t necessarily agree on the methods that Anne wants to utilize, but I think there’s something inherently desirable about having a wide-open ocean in front of you. Yes, it’s dangerous and yes, it’s scary, but there is something really wonderful about being out there and being able to be yourself with your friends and not having to answer to anybody and not having to conform to these roles

Sam: Not a lot of people realize that piracy the way that we conceive of it in pop culture today only existed for about 15 years, and yet it has become a mainstay of our cultural and historical imaginations. People love pirates, yet we don’t often stop to ask why do we find it so fascinating and compelling that we keep telling stories about it hundreds of years later, even though it objectively did not happen for very long and barely made a blip in the history of the British Navy? It’s because on some level we all know these are people who are trying to be free, trying to live independently, trying to live their best life under the thumb of oppressors in the best way they can, and dressed in the pirate sheen, that story is universal and timeless. I think that’s why we love pirates so much, even if people don’t realize it.

Kendra: Also really cool outfits. A good look. Everyone looks cool in a leather duster and a bandanna.

So it seems like that British propaganda campaign backfired pretty spectacularly.

Kendra: Historically, people love a bad boy. They love an outlaw, they love a cool rebel. You can’t get around that.

Will there be more? It sounds like the door was left open…

Sam: We would love to tell more stories with Anne and Read and the whole crew. We think there are an endless number of stories to be told here, and we really hope to be able to continue, so fingers crossed. If people like it, we will happily make more.

Filed under: All Ages

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Crafting the Audacity, One Work at a Time, a guest post by author Brittany N. Williams

ADVERTISEMENT