Writer Jim Ottaviani on adapting Edward O. Wilson’s Naturalist | Interview

Jim Ottaviani is no stranger to writing about the lives and works of scientists, having scripted graphic novels about Niels Bohr, Richard Feynman, Harry Harlow, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Alan Turing, Stephen Hawking and Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas…among many others.

Jim Ottaviani is no stranger to writing about the lives and works of scientists, having scripted graphic novels about Niels Bohr, Richard Feynman, Harry Harlow, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Alan Turing, Stephen Hawking and Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas…among many others.

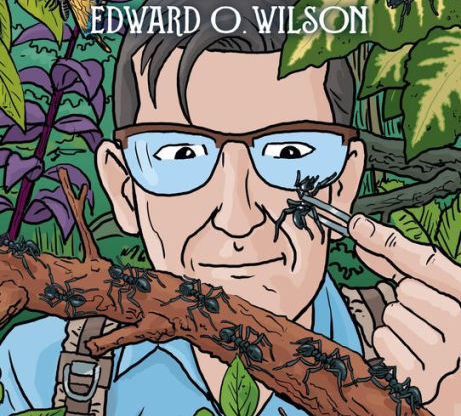

His latest work, Naturalist: A Graphic Adaptation is a bit different than the bulk of Ottaviani’s bibliography, though, as rather than writing his own biography of a scientist, he is here adapting the autobiography of a scientist, Edward O. Wilson’s 1994 Naturalist.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

And, as it turns out, that scientist had some input to share during the process.

In his version of Naturalist, Wilson wrote that “Science is modern civilization’s highest achievement, but it has few heroes,” which can have an air of irony when read today, considering that many might consider Wilson himself to be one such hero.

The preeminent biologist is one of the world’s foremost experts in myrmecology, the study of ants, and he has been called the father of sociobiology and biodiversity. He’s also been compared to Darwin repeatedly. Wilson has written over 20 books, and won Pulitzer prizes for two of them.

Of those books, Naturalist is the first that has been adapted into the comics medium, by Ottaviani and his artistic collaborator C.M. Butzer. Their version of Naturalist should introduce Wilson, his work and his ideas to a whole new audience, including a generation of readers that were way too young to read the prose original.

Perhaps after doing so, some of those readers will find a scientist hero in Wilson.

I took the opportunity of Naturalist: A Graphic Adaptation‘s publication to check in with Ottaviani, and ask about how this book about a scientist differed from so many of the others he’s written.

I am going to begin this interview by confessing my own ignorance. I was not familiar with Wilson before reading this book. When I looked him up after reading it, I was somewhat shocked at just how eminent he is, having been referred to repeatedly as “the new Darwin,” and I then felt a little foolish for my ignorance. Do you think Wilson is as well known by the general public as he should be? Is the fact that he’s not a household name, like the, um, old Darwin a symptom of our society’s lack of appreciation for the sciences?

Ottaviani: Perhaps it is, but I wonder how many scientists who’ve earned similar amounts of respect from their peers are household names. I try to keep up with the world of science—not easy, since it’s as big as the whole world, right?—and I don’t think I could name more than a couple of dozen off the top of my head, and even fewer if you don’t allow me to include those who are famous for their roles in public outreach.

That’s not to say I disagree with your premise! I think the world would be better off if more of us were keeping up with Jane Goodall instead of with the Kardashians, and Wilson is less well-known than he should be, even though he’s an excellent communicator to the general public.

I was curious about your previous experience with Wilson, his work and his writing before you began adapting Naturalist. I know the word can sound strange when applied to a scientist but, well, would you have considered yourself a fan of Wilsons?

Here I’ll mention Jane Goodall again, since I had her in the same category as Wilson prior to doing books about them. I knew who they were, I could say a couple words about each—Chimpanzees and tools! Ants and sociobiology!—but if I was honest with myself, my understanding of their importance was neither broad nor deep. They were famous because they were famous, and I learned a huge amount about why over the course of writing about them.

That’s one of the best things about writing books, really: it gives you an excuse, and motivation, to learn new things.

Setting his discoveries and theories aside for a moment, when you approached his original, prose version of Naturalist, how would you assess him as a writer?

I didn’t read many of his scientific papers, but those are written for specialists anyway. But as for the stuff intended for people like you and me? Simply put, he’s an excellent writer, and has a couple of Pulitzer prizes to show for it.

You’ve written graphic novels based on the lives of many scientists before, but in this case you are directly adapting the scientist’s own autobiography into the comics medium. How different a process is that? And do you find it easier, harder or just different…?

The process was quite different than my usual one, in part because of the rules—well, “rules”—our editor Rebecca Bright gave me. She asked me not to go outside the text of the original, so I didn’t have to read far and wide to build the story. Not that I didn’t do a little extra reading and listening and watching, both to broaden my perspective and get a feel for his speaking voice. And not that I didn’t, in the end, cheat as a result of my extracurricular activity! There were a few grace notes that I discovered in other sources that I couldn’t help but include, and Rebecca was kind enough to look the other way in those cases.

The basics of constructing a graphic novel remained the same, though: Look at all the information you have at hand and figure out how to shape that into a good story. My copy of his book is beat up and full of underlining and notes in the margins and questions to myself like “skip this?”, “great image”, et cetera. The fact that most of the information came from one place just made this typical part of the process go faster.

It occurred to me during the passage where you and Butzer are sharing the letters between Wilson and his wife as part of the narrative that there must have been a fairly laborious process of cutting things out of the story, given how much you would have had to work with. Was there a lot of killing of your darlings in the work on this, in order to turn it into an engaging comics narrative?

The perfect follow-up question, Caleb! That’s the hard part of any book, and it was no easier here. I ran the numbers after I was done, and I turned a 112,000 word work of prose into a graphic novel that only gave you 29,000 of those words. The images deliver some of what’s missing—a picture being worth…well, maybe not a thousand words, but it’s a lot—but they couldn’t do everything. And I didn’t think they needed to do everything. So finding the story-within-the-story that works for a graphic novel meant setting plenty of great material aside.

But hey, the original is still there for anyone who wants something more, or something different!

I think one of the things that makes Naturalist so interesting is that you and Butzer, and, of course, Wilson in his original, are telling a story that goes well beyond just a recounting of his scientific accomplishments and theories, and includes amusing childhood anecdotes, meditations on religion and faith, some inter-office drama among faculty and thoughts on race relations. Are there aspects of Wilson’s Naturalist that seem particularly relevant to us today, beyond the science?

Oh, yes, and that’s why I agreed to the project and that’s why Island Press— the leading not-for-profit publisher on sustainability and the environment—wanted to do it in the first place.

There are many things to learn about how to view the world as a scientist, how to work with others and the like. But for me, the most important part of the book is Wilson’s awakening to, and work on, conservation, so that’s one of the things we tried to highlight in this adaptation.

Is it different working on a comic about a still-living scientist? That is, did you ever feel any pressure, like Wilson could be looking over your shoulder, or judging what you’ve produced in a way that some previous projects were free of?

While I wouldn’t say I felt any pressure, other than the usual deadline stuff, I was 1,000% aware that he was going to look at what I did and comment on it. And, you know, like we mentioned before, he has a couple of Pulitzers; he’s more than earned the right to have opinions about writing, not to mention an adaptation of something he wrote! And I knew if push came to shove, if we disagreed his opinion would carry the day.

Have you had any reaction from Wilson himself?

Yup, and push never came to shove, even though I did something that made me nervous…really nervous!

I changed his ending. Not in the sense of making something up, but I saw poetry in a passage that occurs a little before where his original book ends, so that’s where I stopped our version. Fortunately, Rebecca liked that idea, and he did too!

So when we talked on the phone, and it was only a couple of times as I recall, it was all very supportive and constructive. He corrected things here and there and offered suggestions here and there as well.

For lack of a better way to say it, he gets comics. I don’t know that he’d thought hard about them before, but either way, like almost every scientist or engineer or astronaut I’ve worked with, he didn’t need any coaching to grasp the medium’s strengths, its limitations, its ability to layer information in a panel, its accessibility, etc.

And also like so many folks at the top of their field, he’s secure in what he knows, and trusted Chris and me to do our jobs well.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

If there was one thing that you’d like young readers to take away from Naturalist, either a piece of information or a way of looking at the world, what would you like it to be…?

Wow, that’s a hard question to answer in just a few words, but the way you phrase your question suggests a jumping-off point, so how about this: Each of us is an integral part of the world. And I’d say a special one, too: To paraphrase Carl Sagan, you are a way for the world to know itself.

This is amazing. We’re in an ongoing story, one we don’t want to see end, and it’s set in a world we don’t completely understand. That means our job, and it’s a joyful one, is to uncover mysteries, explore, and shape this story for the better at the same time we live it.

So, how did you feel about ants before you began working on this project, and have your feelings about them changed at all as a result of it?

From the very big to the pretty small, eh? No big change, I gotta say. I loved ’em before—except when they get into our kitchen—and love ’em more now!

May I ask what you’re currently working on, or what projects you have on the near-horizon, that might be at the stage where you can talk about them….?

There’s only one I think I can talk about right now. I’m right in the thick of doing a biography of Einstein for First Second, with artist Jerel Dye. I’m not sure when it will come out, but I can tell you that Jerel is doing beautiful work. I’m working on a couple of other things as well, but they’re in the early stages and haven’t been announced yet.

Filed under: Interviews, Young Adult

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

The Age of Queer Defiance, a guest post by Matthew Hubbard

ADVERTISEMENT