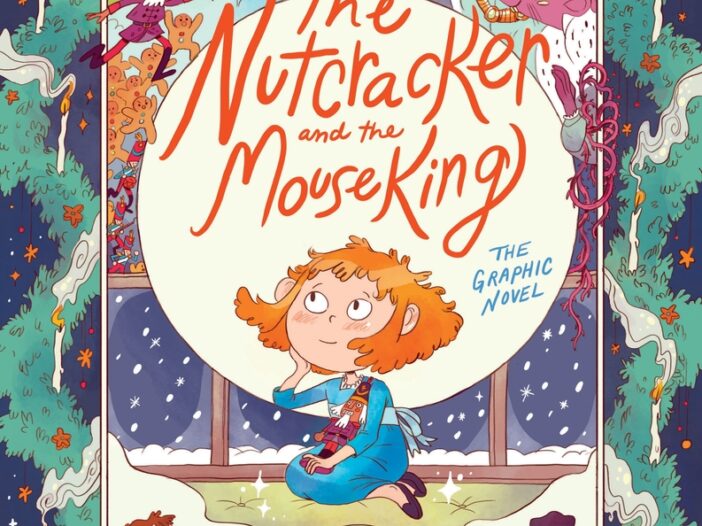

Review: ‘The Nutcracker and The Mouse King’

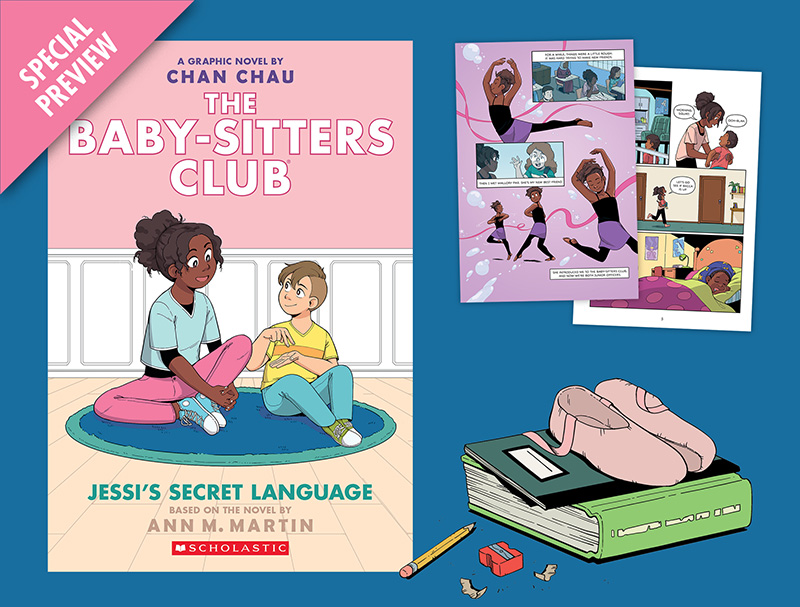

The Nutcracker and the Mouse King: The Graphic Novel

Writer/artist: Natalie Andrewson

First Second Books; $18.99

Everyone knows the story of The Nutcracker, or, at least, a version of the story of The Nutcracker. Tchaikovsky’s omnipresent holiday ballet has long since become the preeminent version of the story, but it’s an adaptation of an adaptation, based on Alexandre Dumas’ version of E.T. A. Hoffman’s 1816 novella, The Nutcracker and The Mouse King. Therefore, while the version of The Nutcracker you probably think of when you think of The Nutcracker overlaps quite a bit with the earliest portions of Hoffman’s original story, there’s a great deal left out.

Cartoonist Natalie Andrewson’s comics adaptation is of Hoffman’s original story, to the degree that his name is on the cover with hers, and it is therefore differentiated from so many other Nutcracker adaptations not simply by its medium (that is, comics), but also by its content. Only the first five of its fourteen chapters will be familiar to those who have seen the ballet and/or any of the many, many pop culture derivations of it.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

After the familiar sequences of Marie, Fritz, Drosselmeyer and the battle between the Nutcracker-lead toy soldiers and the Mouse King’s rodent army, Marie awakens in bed, her bloodied arm bandaged up and giving a delerious account of the carnage in the living room that sounds like a fever dream to her family and their doctor (“It seems Marie has wound fever,” the doctor declares after pulling a thermometer out of her mouth with a “Pop!”).

Drosselmeyer tells her and Fritz bedtime stories though, which Andrewson dramatizes, and which wind about, eventually tying into the doings of the Nutcracker and the Mouse King in perhaps unexpected ways. Meanwhile, between Drosselmeyer’s tales, the Mouse King visits Marie every night for three nights in a fairy tale-like sequence, demanding she sacrifice various possessions in order to save the Nutcracker. No one seems to believe these stories of Marie’s, either, until eventually the evidence becomes overwhelming, and Drosselmeyer and her family join her in the Nutcracker Prince’s kingdom at the happy ending.

Though primarily associated with the kinetic art of dance, Hoffman’s story turns out to be quite well-suited to the comics medium. Especially so given Andrewson’s highly cartoony design and the near-riot of bright colors she applies to the art (the villain of the story, for example, is bright pink). As a result, no matter how dramatic or fairy tale-dark certain scenes or images might be, Andrewson’s book always has one foot rather firmly planted in the exaggerated, slightly silly, humorous facet of comics.

Her Nutcracker and The Mouse King thus looks funny, and it quite often is funny. Drosselmeyer’s supposed ugliness and arrogance or Fritz’s petulance or penchant towards being a know-it-all don’t seem so much like character flaws as reliable sources of gags, and the initial toy-vs.-mouse battle plays out in a funnier, more literal way than dance or even prose could have achieved, with the mice tearing apart soldiers, or, in the case of the gingerbread men reinforcements, literally eating them alive.

Likewise, the curse put upon Princess Pirlipat, giving her a giant head and jaws, is more funny than scary, and the weird look of the Nutcracker himself, rather central to the story, is clear and unequivocal to the reader, and another source of humor. In that respect, Andrewson’s telling helps restore elements of the story that are rather easily lost in more popular re-tellings.

In her author’s note following the comic, Andrewson talks a bit about the difficulties and pressures of adapting such an often-told story—the 2018 big budget film The Nutcracker and The Four Realms came out while she was working on her book, for example—and what attracted her to it: Not only the fever dream aspects of some of Marie’s experiences, but also the way in which everyone around the young heroine seems so quick to dismiss her imaginative world as a bad thing, and something to be minimized or ignored. Marie is, of course, eventually vindicated, and that which she was told to minimize eventually overwhelms her, her family and her whole world…and all for the better.

In that regard, Marie is a relatable hero not only for a young cartoonist, but for any imaginative child. Of course, the heroine of the Nutcracker would have to be, wouldn’t she, in order to justify the tale she’s at the center of living so long and growing so prominent over two centuries now?

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Reviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT