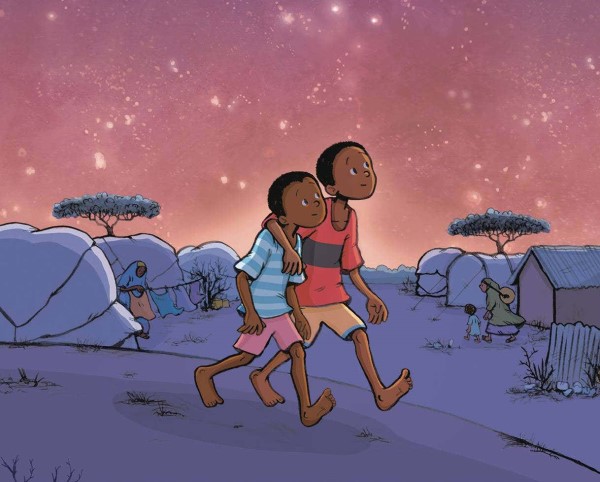

Interview: Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed on ‘When Stars Are Scattered’

Roller Girl and All’s Faire in Middle School cartoonist Victoria Jamieson’s latest graphic novel is quite different from her previous work, but there’s a pretty good reason for that. The story she’s telling in When Stars Are Scattered isn’t her story, but that of her collaborator, Omar Mohamed.

Mohamed and his younger brother Hassan were just toddlers in Somalia when they were separated from their mother and forced to flee to the safety of a Kenyan refugee camp. There they were adopted by a kindly older woman who had lost her own children, but they never stopped looking for their mother. As Mohamed grew older, he became increasingly torn between pursuing an education in the camp, one of the few things he could do to improve his chances of leaving someday, and caring for his little brother, who suffered from seizures and could speak but a single word: “Hooyo.”

Mohamed and his younger brother Hassan were just toddlers in Somalia when they were separated from their mother and forced to flee to the safety of a Kenyan refugee camp. There they were adopted by a kindly older woman who had lost her own children, but they never stopped looking for their mother. As Mohamed grew older, he became increasingly torn between pursuing an education in the camp, one of the few things he could do to improve his chances of leaving someday, and caring for his little brother, who suffered from seizures and could speak but a single word: “Hooyo.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

After arriving in America in 2009, it was a story that Mohamed wanted to tell, even while his life story was still very much in progress. Mohamed earned a degree in international development, became a United States citizen, married and had five children, worked with the Church World Service humanitarian aid group, and founded Refugee Strong, a project focused on helping students in refugee camps.

He was working on a memoir about his childhood when he first met a fellow local volunteer named Victoria Jamieson. Suddenly he had an opportunity to tell the story of growing up in a refugee camp in a very different way than the one he originally imagined.

Their graphic novel chronicles Mohamed and Hassan’s childhood, how they arrived at the Dadaab refugee camp, what life was like there and, ultimately, how they managed to escape it for a new life in the United States.

We spoke with Jamieson and Mohamed about When Stars Are Scattered via email.

First, I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about the reception the book has received since its release this spring. Obviously promoting a book during a pandemic is a bit different than it would have been otherwise, but have you been able to get feedback from readers?

Omar Mohamed: I’ve received a lot of feedback on Twitter and by email from readers who have read the book and are saying nice things about it. Many have expressed their thanks for sharing my story. The feedback has been very welcoming and positive.

Victoria Jamieson: I’ve been hearing very positive feedback as well. I’ve heard some really wonderful stories of young people who decided to take action after reading the book. One young reader raised funds to donate to Refugee Strong; another wrote letters to her members of Congress, asking for the cap on the number of refugees admitted to the U.S. to be raised. It is an honor to write books for young readers, and I am inspired by their passion every day.

I was honestly a little shocked to get to the afterword and discover that Omar and Hassan actually do eventually find their mother, given that the search for her plays such a big part of the story. Was their reunion not included in the story because of the time frame covered, or because elements of it are still unresolved, or do you guys intend to collaborate on future stories set after When Stars Are Scattered?

Mohamed: It wasn’t included because the book is focused on when I was 11, 12 and 13 years old and we wanted to keep the focus on that time. To include events that happened many years in the future would have been too much. As for future stories or collaborations… anything can happen, who knows!

Victoria, we know from reading the book how it is that Omar came to the United States and was in a position to meet you. Could you tell us a little bit about how it was that you began volunteering with refugees, and thus first met Omar?

Jamieson: I began volunteering with a local resettlement agency in Portland, Oregon, back when the news was filled with stories of the Syrian refugee crisis. These stories seemed so far away, and I felt helpless to make any sort of difference from my home in the United States. I began researching local refugee resettlement agencies, and I quickly learned that there are many, many ways for people to get involved, even in your own neighborhood!

I met many new immigrants and refugees in Portland through my volunteer work, and I was privileged to hear some of their stories. When my family moved to Pennsylvania, I was taking a tour through Church World Service, the resettlement agency where Omar works. One of Omar’s co-workers introduced us, and we began talking about possibly writing a story together.

Victoria, you mention in your author’s note that before embarking on this particular project, you had begun to wonder how your background as a graphic novelist could be put to use to help refugees. This book seems like such a departure from your earlier work, I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about how you decided that this was the story you wanted to tell next in your career?

Jamieson: I honestly did not know what this story would look like…even well into the making of When Stars Are Scattered! In the beginning, I was following a curiosity and a desire to become personally involved in an issue I felt strongly about. I think I can say that both Omar and I took a leap of faith when we decided to collaborate on this book. Neither one of us really knew how it would turn out! I am so grateful that I met Omar and he agreed to share his story with me.

How different was this process from that of making Roller Girl or All’s Faire in Middle School? I imagine that, in addition to having a collaborator, a great deal more research was necessary.

Jamieson: Yes, this book was different on both counts. My previous books were based on my own imagination and life experiences, and I was free to imagine any plot twists or character developments that I wanted. With this book, I quickly realized that any time I tried to invent a convenient plot twist or development, it was inevitably the wrong choice! Instead, I learned to talk to Omar and ask him to elaborate or speak more about a point in the book, and the way forward would reveal itself.

Working with Omar made me a better listener of stories, and I hope to carry that forward in future books.

As for research, both Omar and I were very determined to make this book as accurate as possible. That involved a good deal of research on my end, and constant contact with Omar as I was creating the art to make sure my drawings were accurate. We consulted several early readers, both former and current residents of Dadaab, to help flag any inaccuracies in the book.

Omar, when you were growing up in Dadaab, did you have any experience with comic books? I understand you were originally trying to tell your story in prose for an adult audience. What helped you change your mind to collaborate with Victoria on a graphic novel for younger readers?

Mohamed: We really loved picture books in the refugee camp. Of the few books we had in the camp, most were picture books, even the ones used by teachers. In the whole school we maybe had three or four books for the entire school, and you might see that book once or twice a year. I remember a book called Hallo Children—it’s a very famous book in Africa.

In the refugee camp, because we didn’t have TV or the internet, the pictures in books were something to look at. Also, because English was not our first language, it was helpful to have the pictures to follow along with.

Omar, during the interview with David at the United Nations that takes place in the book, you have to retell and relive the most traumatic day of your life, which was extremely difficult for you as a boy. Do you mind if I ask how it is telling people that story with Victoria now, and having it out in the world, to be discovered by young readers?

Mohamed: The difference now is that I am telling my story by my choice. In the interviews, you don’t have a choice, you have to tell the interviewer who you are, and why you are who you are.

This time, no one forced me; this is me wanting to share my story with the rest of the world. I want to be a voice for the voiceless—those refugees who are still struggling in the camps. My story is one of many millions of other stories from around the world. It is hard sharing your story with a stranger in a resettlement interview when you don’t know how it will affect your life.

I also know how difficult it is to share your story because I worked as an interpreter in the camp during these resettlement interviews, so I heard many other people share their stories. This encouraged me to share my story voluntarily.

I was so immersed in the story that I was surprised to see Victoria’s mention of a couple of characters needing to be invented in her author’s note. Can you guys tell us a little about the fictionalizing of the true story, and striking the right balance? Were there characters who were composites of real people, or stand-ins created to protect the privacy of real people?

Jamieson: Several of the other kids in school are composites of real people. For example, “Jeri” is a very common nickname in the camps, and Omar had said he knew several kids with that name. Nimo and Maryam also started off as fictionalized characters, but they actually did end up bearing striking resemblances to real kids Omar grew up with!

The United States government is not particularly receptive to taking in refugees these days. If you could each change one thing about the current discourse regarding refugees in America, what would it be?

Mohamed: The U.S. used to be one of the major countries that accepted refugees, and also a major financial supporter of the United Nations. Right now, the number of accepted refugees this year is around 32,000, an historically low number. But beyond this, every step of the process has been made very difficult, and add in COVID-19, and there are very, very few refugees coming to the US.

It has been a very sad two to three years for refugees around the world being processed to come to America. Right now, the President of the United States decides the number of refugees allowed into the country. Congress has recently proposed new legislation that outlines a base number of refugees to be accepted, granting the president only the power to increase that number, but not go below the minimum. I think this would be a good step forward.

Jamieson: I would ask the United States to reflect on its own involvement in creating the refugee crisis worldwide. Many developed nations are quick to close their borders and say “not our problem” when faced with people seeking refuge. It’s not commonly discussed how much of the instability in other countries is due to the direct involvement of the U.S. and other western countries. I would hope that the United States would admit to the wrongs of our past and begin making amends, rather than turning our backs on a crisis we helped create.

There are several heartbreaking moments in the book, but the first one that really affected me was seeing the boys playing soccer/football with a “ball” made of plastic bags. Even though I generally feel pretty powerless when it comes to huge problems like the global refugee crisis, I found myself thinking, “Heck, even I can afford to buy a soccer ball and ship it to Africa.”

I felt both a little guilty and a little ignorant for not knowing or even thinking about the fact that there were boys who needed balls that badly. I know you both work with various organizations, and Omar founded Refugee Strong. Can you suggest ways in which people, perhaps particularly people who feel powerless regarding the scope of the problem, can help refugees like those in Dadaab and elsewhere?

Mohamed: There are many organizations, locally and internationally, that work with refugees, including my own non-profit Refugee Strong. You can make contributions as an individual, or you can involve your community by organizing a fundraiser with your school, friends or family. If you wanted to, for example, specifically donate soccer balls, or educational opportunities for girls, or anything else, you can make a specific note when you donate to Refugee Strong and we will make sure your funds are used for that purpose.

Jamieson: Refugee Strong is a wonderful organization, and Omar returns to Dadaab every year to distribute supplies directly to kids in Dadaab. He hopes to expand its services to camps in other parts of the world, and I’m excited for the future of his organization.

Locally, there are lots of ways to empower immigrants and refugees in your community! You can do an internet search for refugee resettlement agencies in your area. Volunteer opportunities abound, from working as an English coach or cultural navigator, to donations of furniture, clothes, or school supplies to new arrivals. When refugees and immigrants in our communities succeed, we all succeed.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Interviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Coretta Scott King Winners

Monster Befrienders and a Slew of Horror/Comedy: It’s a Blood City Rollers Q&A with V.P. Anderson & Tatiana Hill

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

Hello Mr. Omar,

I read your book ” When Stars are Scattered” and I truly loved reading it. Once I started reading, I just couldn’t put the book down and stop reading. It was a very interesting book to read. It taught me a lot about the life of Refugees and their struggles. I can’t imagine what life must have been in Dadaab without your parents, and having to support a younger brother who has medical problems. I don’t know how you managed all that stuff. One of your most best decisions was going to school instead of not going to school and doing household work because since you got educated, you were able to be successful in life. I hope that you and Hassan are safe and happy now in America. And I also read in the forward that you became a social worker for the U.N. It is so wonderful, that even after being a refugee, you finally got to live your dreams.

I am an ESOL teacher at an urban public school. I am going to begin teaching “When the Stars are Scattered “ in the next couple weeks to my middle school students. Many of my students are refugees from Somalia and have been in the same refugee camp as you. I want them to know that they can be successful. More than that, I want them to know their stories need to be told. Keep being an inspiration to people every where. I would love for them to write letters to you when we finish our book study. I will mail them to Refugee String. ❤️