Review: ‘Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hope’

Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hope

Writers: Lun Zhang and Adrien Gombeaud

Artist: Ameziane

IDW Publishing; $19.99

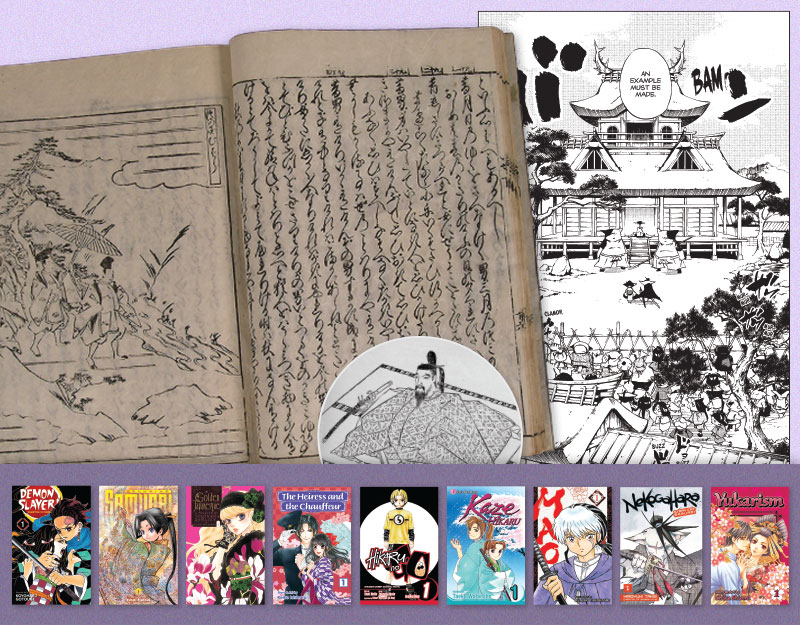

Page 39 of Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hope is a really great page. It’s divided into five panels.

The top panel, stretching across the top tier of the page, offers an overhead view of a bit of the titular square, a corner of roof and swooping bird in the foreground, while in the background artist Ameziane draws a mass of students and demonstrators, all gray and black, holding signs aloft. Before them is a neat row of police officers, standing like columns of olive green.

The second panel is a close-up of the marchers’ shoes, in a variety of styles and colors, as they proceed into the square.

Below that, on the third tier of the page, are a pair of panels, both of which remain close-up on the shoes. In the first, the marchers have stopped, having come toe to toe with the drab green shoes of the lines of policemen. In the next, the colorful shoes are marching again, the soldiers having parted to let them pass.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The final panel on the page is a repeat of the first, but now the square is completely filled with the marchers, and there’s no sign of the police..

There are words on the page, of course, some 100 or so words of narration running horizontally in the white gutters between each tier of panels, but here, those words are almost superfluous. On this page, it is the imagery that not only tells the story, but also brings a great deal of drama and suspense to it. And Tiananmen 1989 is an extremely suspenseful book, particularly for readers who only know the few details of the events that made international news; that is, you know incredible violence is coming, just not when, exactly.

It’s a great page, but, unfortunately, the reason that page 39 stands out as much as it does is that it’s one of the few in which the art in the panels drive the comic, rather than just coming along for the ride as the narration tells the story.

It’s an important story, a story that needs to be told and a story that needs to be learned by young people all around the world, as state-sanctioned violence against young protesters continues to this day, not just in China, but also, with the out-of-proportion response of law enforcement to nationwide Black Lives Matter protests, in the United States as well.

It is not, however, great comics.

Writer Lun Zhang invents a “fictional twin,” “a man who had a life very much like” the one he himself lived, which better allows him and co-writer Adrien Gombeaud to tell the story of the pro-democracy student movement in 1980s China and how the ruling party eventually sought to crush it, rather than telling his own, personal autobiography.

Zhang’s twin addresses the reader directly, as if telling readers the story, although some artistic flourishes are taken to present it as something other than the conversation the first page suggests it will be. By page two, our narrator is on a stage with a red curtain and a beautifully decorated backdrop behind him. He says he has learned to think of Tiananmen Square as “a theater of history,” and this metaphor carries throughout the book, starting before even the first panels of the story with a “dramatis personae” section laying out prominent figures in the student movement, China’s intellectuals, and important players in the government.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The book, divided into “acts” like a play, will move from images of the narrator on the stage to dramatizations of his story, but his voice is a constant, with most of the story being told in prose narration, rather than in dialogue between characters.

There is a lot of information, with the narrator talking about his own life and China’s history from the late 1950s to about 1985 or so, when things begin to slow down, and then, by Act II, they become slower still, as we get to the spring of 1989, the students taking the square and initiating hunger strikes, and the government trying to figure out how to react, a process that includes various stumbling attempts at engagement as well as ignoring them until they finally employ guns and tanks.

Following the five-act story and its short epilogue, there are pictures of some artifacts of the time and explanations of each, a timeline of the “Chinese century” from 1919 to 2019, and Zhang’s explanation of what the movement was and wasn’t, discussing the subtleties between a revolution, in which the government would have been overthrown violently and started anew, and a sort of reformation, in which the demonstrators sought to urge the government to live up to its own ideals. He also helps put the events in the context of the 30 years of history that followed.

It makes for a pretty great introduction to a difficult and somewhat nebulous subject, and a rather effective textbook, even if the art/word ratio is out of whack throughout. The comics reader in me found it wanting, but then, I suspect it was made as a comic in large part to communicate its story more widely and effectively than it might have in prose, and the transmission of that story is the more important goal of the creators anyway.

Filed under: Reviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT