Monthly mini-reviews: ‘Donut The Destroyer’, ‘When Stars Are Scattered’ and more

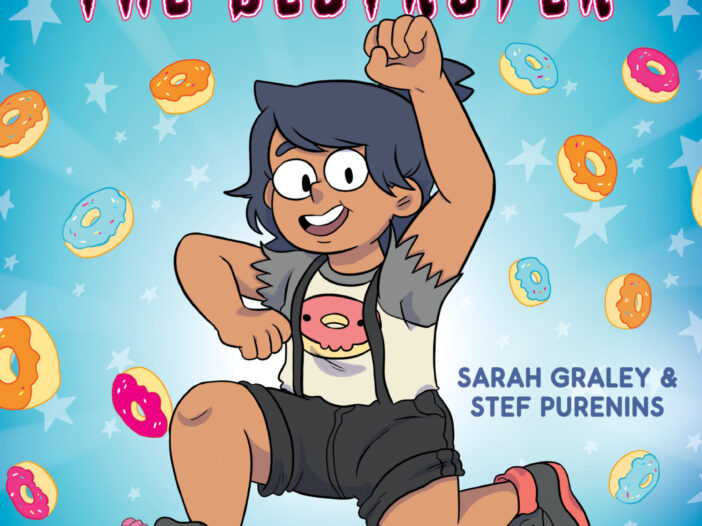

Donut The Destroyer

Writers: Sarah Graley and Stef Purenins

Artist: Sarah Graley

Graphix; $14.99

Donut has been accepted to the prestigious school of her choice: Lionheart Academy for Heroes, where the kids of her world can learn to use their special abilities for good.

Her otherwise doting and supportive parents are less-than-pleased, however; Mr. and Mrs. Destroyer are among the most notorious of supervillains, and they had hoped their super-strong daughter would attend Skullfire Academy and follow in their footsteps.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Even more disappointed is Donut’s former constant companion Ivy, who uses her own superpowers to try to sabotage Donut’s career at Lionheart, get her kicked out of school and thus force her into joining her at Skullfire.

Can Donut overcome all of this adversity, not to mention the suspicions and sidelong glances of her new classmates? If she really has what it takes to be a hero, then that shouldn’t be a problem.

With more than a passing resemblance to the premise of the super-popular manga series My Hero Academia, this latest offering from Sarah Graley (Glitch, Kim Reaper) shouldn’t have too much trouble finding and charming an audience. Stylistically, the book couldn’t be more different, and Graley and her collaborator Stef Purenins manage to infuse genuine, immediate emotional conflict in the light genre parody. That is, while kids might not know exactly what it’s like to fight monsters and villains bare-handed, they’ll still know what it’s like to feel out of place, to be embarrassed by their parents, or to be sad about changes in a long-time relationship.

When Stars Are Scattered

Writers: Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed

Artist: Victoria Jamieson

Penguin Random House; $12.99

Victoria Jamieson, the cartoonist responsible for Roller Girl and All’s Faire In Middle School, teams with Somalian refugee Omar Mohamed to tell a fictionalized graphic novel account of Mohamed’s early life growing up in Dadaab, a refugee camp in Kenya. Life is rough for everyone in a refugee camp, of course, but Omar faces challenges many of his neighbors do not: He saw his father gunned down and became separated from his mother while fleeing, so he is now effectively an orphan, caring for his younger brother Hassan, who suffers from seizures and is only able to say a single word (an older woman named Fatuma lives in a tent next to them, and acts as their foster mother).

Omar takes caring for his brother very seriously, and has essentially devoted his young life to the task, eschewing attending school with other kids his age. Eventually, he’s convinced to give school a shot, though, and he finds he excels at it. As challenging as Omar’s life might be, he realizes that there are many others with their own, perhaps worse challenges. His best friend, for example, has a bad limp, and an abusive father. Another playmate doesn’t do well enough in primary school to advance to secondary school. The smartest girl in his class is forced to drop out to marry.

There’s a lot of heartbreak in Mohamed’s story despite the eventual happy ending—Mohamed met Jamieson in Pennsylvania, and they collaborated on this book, so we know he eventually makes it out of camp and to America. Escaping the camp felt far from certain to the young Mohamed, and that hopelessness is clear throughout the book. In fact, it wasn’t even his dream the way it was that of so many of his peers; instead, Mohamed dreamed of being reunited with his lost mother, and being able to return to their family farm in Somalia, once the fighting stopped.

It can be a tough read because of its emotional content and the injustice that kids like Omar, Hassan and their friends have to live their lives one way while children in other countries get to live theirs another way, but it’s written and drawn in such a way that it is, paradoxically, a fun read. Omar and Hassan are both sharply realized characters, and for all the sad things they face, there are moments of high drama, light humor and inspiring faith and resilience.

After the story, which covers years in its 255 pages and certainly reads and feels like a novel, there’s an afterword and a pair of author’s notes that tells us what happened after the last pages, and how the book came about. Apparently, Mohamed was originally interested in writing a memoir for grown-ups when he met Jamieson, whose specialty was obviously comics for younger readers.

I would say it worked out quite well. Jamieson’s gentle, slightly cartoony art softens the impact of some of the more tragic bits, and gives the story an absorbing immediacy that prose, even the best-written prose, can never really match. As a comic, When Stars Are Scattered is able to put young readers directly in the camp with Omar and Hassan.

Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed

Writer: Laurie Halse Anderson

Artist: Leila del Duca

DC Comics; $16.99

Born and raised on a secret island nation before beginning her superhero career in America, Wonder Woman has often been portrayed as an outsider character of sorts. Originally, she had come from a superior civilization to defend the world from fascism and proselytize the Amazon way to benighted America. Later she was presented as an immigrant, and more recently the culture-clash between Themyscira and the modern world has been played for fish-out-of-water laughs.

But in every version of the Wonder Woman story, she always comes to America by choice, and on a mission. Not so with Tempest Tossed, in which writer Laurie Halse Anderson makes a teenage Diana of Themyscira into a refugee.

Or, at least, she goes through the refugee experience. After about 30 pages spent introducing us to this version of Diana and this version of Themyscira, a man arrives on the beach of the mythical island—but this man isn’t American pilot Steve Trevor, he’s one of a group of refugees whose boats are washing up on the island. They’ve fled their home country—it’s not named, but is presumably meant to be Syria—and holes in the magical force field that keeps Themyscira invisible to the outside world have allowed them accidental entrance onto the forbidden island. While her people are rounding them up and tossing them back out to sea, Diana impulsively dives into the water, rescues all the drowning children and puts them safely back in their raft…but finds herself outside of the barrier herself.

From there, Diana gets an abbreviated tour of the refugee experience. Her raft arrives in Greece, where she and the others are processed into a refugee camp, where she spends some time. She’s plucked from there by a pair of United Nations employees named—get this—Steve and Trevor, who are impressed with her amazing language abilities. They train her a bit, and then take her to America, where she lives with a Polish refugee named Henke Cukierek and her granddaughter Raissa, and Diana joins the latter in all sorts of charitable work with various neighborhood girls, eventually learning of a human-trafficking ring targeting them.

Anderson does an extremely admirable job of using one of comics’ most popular superheroes as a prism to explore difficult issues of human migration in the 21st century, a character for whom such issues are a natural, if counterintuitiv,e fit. She also offers a great deal of interesting observations about Diana’s unusual situation both on and off the island, applying real-world concerns like, say, puberty to a character generally shows as so perfect as to be above such portrayals of weakness and awkwardness.

However inspired or well-executed various passages of the book might be, however, they never quite come together as a single, coherent work. Despite being a graphic novel, it actually reads more like a handful of single-issue comic books, part of an ongoing, serially-produced title that isn’t over yet. While certain elements are revisited throughout, others seem dropped, or even forgotten, and conflicts arise but remain unresolved, with a villain being introduced late in the story, and then dispatched with quite quickly.

DC has been remarkably successful thus far in producing original graphic novels for kids and young adults written by popular prose writers new to the field, but Tempest Tossed is one of the first I’ve read that doesn’t quite work as well as it should; in fact, it seems like it might have actually been better off as a prose novel than a graphic one.

Young Justice Vol. 2: Lost in the Multiverse

Writer: Brian Michael Bendis

Artists: John Timms, André Lima Araújo, Nick Derington and others

DC Comics; $24.99

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The first volume of writer Brian Michael Bendis’ revival of Young Justice, the 1998-2003 series starring DC’s most prominent teenage heroes and the inspiration for the popular cartoon series, was quite solidly made and showed a lot of promise. Unfortunately, the second volume fails to live up to that promise, quite quickly devolving into just one more quite-complicated shared-setting comic for only the more devoted fans.

In the previous volume, Bendis and his artistic collaborators reunited Superboy, Wonder Girl, Impulse and the previous Robin Tim Drake in an adventure that added Amethyst, Princess of Gemworld and new characters Jinny Hex and Teen Lantern to the new team. In this volume, the half-dozen heroes bounce around alternate dimensions a bit, spending most of their time on Earth-3 and the world of 1996’s Kingdom Come, before returning to their home world and immediately teaming-up with the stars of the three other comics in Bendis’ “Wonder Comics” imprint: Naomi, The Wonder Twins and Dial H For Hero.

Along the way, Jinny Hex and Teen Lantern finally get parts of their origin stories told, Tim Drake rather randomly gets a new costume and changes his code name from “Robin” to that of his evil counterpart from another dimension and the question of the characters’ screwy, untold secret histories of the last few years, presented as a compelling mystery in the first volume, is barely even touched upon.

This series is apparently already pitched at a rather small and specialized audience, and it appears one also needs to keep up with the weekly twists and turns of the DC Universe line of comics to follow along. All of the artists involved—and there are five of them in the course of just 120 pages—are good, but the book lacks a cohesive look, which was also a problem with the previous volume. In the first 12 issues, Young Justice has already had two “regular” artists, and lots of guests for character-specific sequences.

Filed under: Reviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT