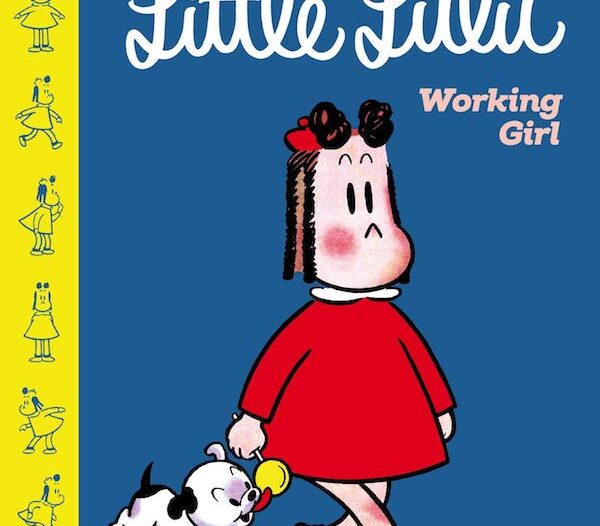

Review: ‘Little Lulu: Working Girl’

Little Lulu: Working Girl

Writer/artist: John Stanley

Drawn & Quarterly

This new collection of John Stanley’s Little Lulu comics from the 1940s and 1950s is one of those relatively rare works that presents something of a challenge to one in the business or habit of recommending comics to kids. Stanley’s Little Lulu comics are undoubtedly perfect comics for kids, and they were originally created for kids…although this particular collection of them is rather obviously geared toward adults…although kids will still like it too, even if they don’t bother with all the prose content that comes before and after the 270-pages or so worth of comics.

Perhaps it would be more helpful to discuss the format. The 7.5-by-10-inch hardcover makes for a big book; in fact, it’s a full inch thick! It includes a two-page introduction by author Margaret Atwood, who is probably best known for The Handmaid’s Tale and whose name is currently on a lot of lips because of its new sequel, The Testaments, but who was once an avid reader of Little Lulu, back when the comics were first being released and she herself was still in the target audience.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

There’s also a thorough 14-page article by the volume’s co-editor Frank Young, in which he provides the history of the one-time silent cartoon character and her original creator Marjorie Henderson Buell, some biography of cartoonist John Stanley and how he inherited the character and made her his own in the pages of Dell comic books, and some rather thorough analysis of the stories that appear in this volume, much of which will likely, rightly fly over the heads of younger readers.

What will resonate with young readers—with all readers, really—are the comics themselves, which remain as fun, funny and vital today as they must have been when I was a kid in the 1980s, or when Atwood was reading them and trading them with her brother and friends in the 1940s. Aside from the occasional outdated reference—a coal chute on the side of the house, castor oil—there’s not much that actually dates the stories, and, in that respect, Stanley’s Little Lulu is not unlike Carl Barks’ Disney comics or Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. That is, it’s a truly great work of comics-making genius, bearing a timeless, all-ages appeal that is only ever punctured by a minor detail here or there.

Lulu Moppet is a typical little girl, although she appeared somewhat atypical when she first appeared, by virtue of being a girl (Young puts her in the proper context of a line of 20th century mischievous child protagonists, and Atwood referred to Lulu and friends as “bratty kids,” which were, of course, universally appealing to other bratty kids). An only child, Lulu’s constant companion was Tubby, her overweight neighbor who is, in a way, her everything: Classmate, best friend, confidant, rival, partner, victim, oppressor and love interest. Their constantly shifting roles is one of the many great pleasures of the comic, as Stanley gradually builds them both up into enormously complex characters with rich inner lives and often conflicting desires.

At this early point in the Stanley’s tenure on the comic, there are relatively few characters. Aside from Tubby and Lulu’s parents, the only other character of note here is Alvin, the younger kid that Lulu occasionally has to babysit and keep entertained. Other neighborhood characters appear as needed to suit the particular roles of a story. Some of them are recognizable as members of “the fellers,” the group of boys that Tubby will later hang out with, often at the exclusion of Lulu who, being a girl, isn’t welcome in their clubhouse, but they aren’t yet named and don’t appear with regularity in this volume.

The standard Stanley Little Lulu story features Lulu and Tubby performing some childhood ritual or some form of play: Attending another kid’s birthday party, going to the beach, going to the park, getting lost in the woods, temporarily running away from home, dealing with a neighborhood bully, and so on.

What makes the stories so engaging, beyond Stanley’s obvious mastery of the skills that go into making comics and presenting gags, is how well the cartoonist is able to capture the feeling of being a child, that seeming to occupy a parallel world from the one inhabited and ruled over by grown-ups, an alternate dimension of sorts in which a kid can be themselves when they are playing by themselves or are alone with a fellow kid.

One great, constant source of humor in these comics is the fact that Stanley manages to show us Lulu and Tubby thinking and acting as if they are often in their own worlds, their black dot eyes looking blankly ahead as they go about their business, while also showing us backgrounds of adult passersby reacting to the kids, reinforcing the tension between how they think of themselves and how the world thinks of them.

So if Schulz’s Charlie Brown and friends occupied an eerie universe devoid of adults, Little Lulu and Tubby’s town was just the opposite. Not only did their parents and teachers appear and talk to them, not only did grown-up authority figures try to either organize their play or frustrate it, but the reader will often see someone in the background or foreground looking quizzically at the oblivious kids, or seeming irritated or annoyed by them.

Visually, the kids always seem to be doing something subversive, to be challenging the society they only technically lived in, because being a kid is subversive—or at least often feels like it when you are a kid (And the fact that Lulu was a girl, and thus had to strive against the “no girls allowed” culture of Tubby and the fellers, made her an even more potently subversive figure for some).

The book contains full comic stories of various lengths, as well as several one-page silent gag strips (probably originally created as page-fillers). They are all presented in full-color, in contrast to the black-and-white trade paperback collections that Dark Horse published between 2005-2011 (a smaller, more kid-hand-friendly format).

Among the best of them is a Tubby solo story in which a young couple see him watching them eat through the window of a restaurant, assume he is a needy child and invite him to join them, only to be severely, almost shockingly taken advantage of.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

There’s also the first of several recurring types of stories. Alvin demands Lulu tell him a story, which results in her concocting an elaborate fairy tale like “Little Lulu In Distress” and “Little Lulu and The Seven Dwarfs”; these story-within-the-story comics always grant Stanley license to deviate from the standard suburban milieu.

Later, in “Little Lulu and The Case of The Purloined Popover,” Lulu is punished when her mother assumes she has eaten the popovers meant for desert that night, but Tubby, always suspicious of Mr. Moppet, puts on a fake mustache rigorously investigates the situation, eventually accidentally getting Mr. Moppet to confess. Tubby vs. Mr. Moppet detective stories will later become another staple in the series.

There are also a couple of examples of “Lulu’s Diary,” examples of the then-necessary prose pieces that helped secure comic books more favorable subscription rates in the Golden Age. Here they take the form of a stories written by Lulu herself on a typewriter, and are illustrated by Lulu. In a post-Diary of a Wimpy Kid publishing world, where the illustrated diary format and comic/prose hybrid have become a sub-genre, it’s interesting to see such an extremely early example.

None of these things will necessarily be of great interest to child readers, of course, at least not yet. The comics themselves are, of course, another story: Those should prove just as interesting to today’s young readers as they always have, or, at the very least, nearly so.

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Coretta Scott King Winners

Monster Befrienders and a Slew of Horror/Comedy: It’s a Blood City Rollers Q&A with V.P. Anderson & Tatiana Hill

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Book Review: Keeping Pace by Laurie Morrison

ADVERTISEMENT

I seem to recall reading fascinating tails in Little Lulu about a strange young girl dressed in black who Lulu encountered and would follow to strange adventures in an almost altered universe. I seem to recall Lulu entering this little girls realm by way of a fireplace in old house. The girl’s name was Oola or Ooga or something like that. Maybe she was a recurring character in a story that Lulu told the Alvin? I don’t think I dreamed this! Can anyone help me out here?

She was Oona Goosepimple from the Nancy (and Sluggo) comic books. From Wikipedia: Oona Goosepimple, the spooky-looking child who lives in a haunted house down the road from Nancy’s house. She originally appeared only in the comic book version of the strip, during John Stanley’s tenure in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[45] She appeared in the actual comic strip for the first time on October 16, 2013.