Interview: Brigitte Findakly and Lewis Trondheim

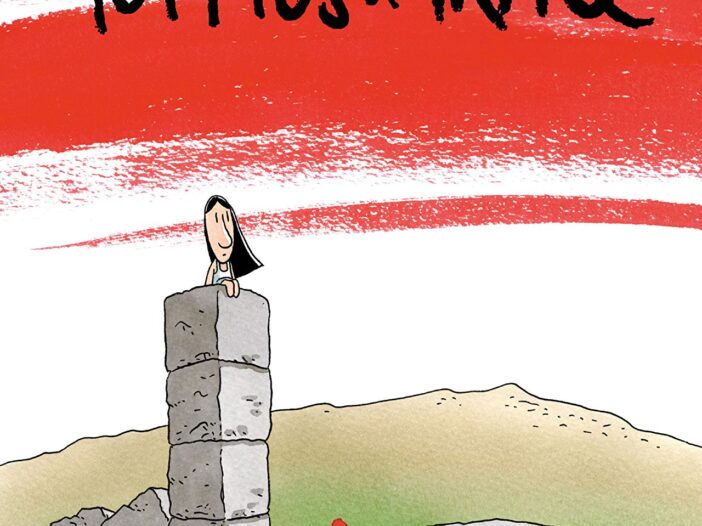

One of the books I mentioned in my SLJ article First-Person Graphic Memoirs Bring Events to Life for Students is Brigitte Findakly and Lewis Trondheim’s Poppies of Iraq, a collection of anecdotes about Findakly’s childhood in Iraq as the daughter of a French mother and an Iraqi father. Findakly wrote and colored the book, and her husband, Lewis Trondheim, was the artist.

I was fortunate to be able to sit down with Findakly and Trondheim at Comic-Con in San Diego in 2017 for an interview. Here’s our conversation about the making of Poppies of Iraq and the reaction from Findakly’s family and others when the comics were first published in France.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

As a child, how aware were you of what was going on?

Findakly: I actually had a very peaceful childhood, despite the coups d’etat, despite the constant police presence and surveillance. I didn’t see any of that. I had a normal childhood.

Trondheim: If there was a coup d’etat, the only change was that there was no school the next morning. So it was good news if there was a coup d’etat, because you got to skip school.

Did you work strictly from your own memories, or did you talk to your family or do other research?

Findakly: 80% of it is what I remembered exactly as I remembered it. I didn’t go back and do research; I didn’t have to struggle to recall it. It was all there. I also think that being an exile crystallizes the memories and helps you keep them in a very pristine way. For the other 20%, often Lewis would ask for clarifications on things as we were discussing the story, and sometimes I had the answer and sometimes I didn’t have the answer and then we would go either to my brother, who is six years older than me, or to my mother. My mother was French but she lived in Iraq for 23 years.

This story has both light and dark moments—on one page you are a child playing with your friends, and on the next your brother and his class are being taken to look at the hanged bodies of insurgents. At the same time, the style of the art takes the edge off some of the more horrific moments. How did you find that balance?

Findakly: It was Lewis who was able to manage that and to ensure there was that balance of light and dark. At first I thought I could tell the story myself, but as I was doing it I realized that it felt too heavy, too dark. Even when I was talking about something happy or something light, it didn’t have the right tone. It came out too sad. So a very gifted cartoonist contacted me [laughs] and I was delighted to accept his help and I’m really pleased with how the collaboration turned out.

Trondheim: It was important to me to mix a little history of the family and a big history of the country.

In the beginning, I was contacted by the newspaper Le Monde, asking me to do short strips about the news. At a certain point I was like, well, why would I tell this other story when I had Brigitte’s story and Brigitte’s story has elements of the news in it? So I thought, well of course, this is the thing that should become the piece for Le Monde. With the potential risk, that maybe we would break up and get divorced by the end of the book.

That’s where some of the episodic nature of the book comes from. It was being serialized in Le Monde weekly, so you were being given a single anecdote each week, and that built up the backbone of the book. And because of the way the news cycle unfolded and the situation in Iraq has changed while we were writing the book, the current events became a sort of pathway or a route back into the past events that we were also talking about.T

Were there stories in this book that you hadn’t shared before—that Lewis didn’t know about?

Findakly: He didn’t know very much of what happened in the book. It’s the same with our children: They know that I was born in Iraq, they know that my father is Iraqi, my mother is French, and they know the broad strokes, but they don’t know any specifics about what my life was like.

The things that are in the book are not the kinds of things that you just tell someone out of the blue. I’m not going to sit down and say “Come, my daughter, my son, my husband, come sit around the table and I’m going to tell you about my childhood in Iraq.” That’s not the way it would happen. My brother has a son and a daughter—they are grown up now—and when they read the book they told me they were very deeply touched and it helped them understand their father much better because they also hadn’t heard these stories.

Trondheim: I was with Brigitte for two, three, four years, then I knew that she came from Iraq, but I didn’t even know whether or not they were Muslim or Christian, because I had never asked the question.

Have your parents seen the book?

Findakly: Yes, of course.

And how did they like it?

Findakly: My mother was really happy when we told her we were going to make this book, because she follows the news in Iraq and she thinks it’s a very important story to share. Before, it was very hard to get my mother to open up. She was always very closed when you would ask her questions about how her life was before. But when we told her we were working on this book, when we would ask her questions for this book, she opened up completely. It was like the floodgates opened—she was telling me all these things I had never imagined even asking.

My parents live right next door to us, so I would go there and ask questions, and sometimes I would get home and get a phone call [from my mother]: “Oh my god, I forgot to tell you this and this and this!”

Trondheim: Brigitte’s mother reads the same newspaper every morning, and she has read it every morning for seven years, and when the book came out there was a full-page excerpt of the book in her newspaper, and it’s the scene where she was serving cakes to people. So she found herself drawn in the paper that she reads every day.

And how was she about that?

Trondheim: She was incredibly happy. Making the book was great, but being in the newspaper was also pretty great.

Findakly: My mother told me that reading the book brought her back to that place and made her relive those experiences.

Did you get any reactions from outside the family, when it was running in Le Monde?

Trondheim: We didn’t receive any letters from the newspaper or anything like that, but when the book has come out in French and when we have been doing signings, and now it has come out in English and we are doing signings at festivals, we have received a lot of commentary.

Findakly: The Iraqi ambassador in France contacted us. The Iraqi cultural service found the book, read it, and passed on to ambassador in France, who also read it, and they loved it. I was not expecting that. I was very surprised to hear that. He invited us to come over and meet with him. He told me that he was so happy to read the book because it showed Iraq as a real place, as a place where people live, where people are happy, and not just the Iraq that you read about in the newspaper all the time.

Trondheim: At the signing in Paris there were two cultural attaches from the Iraqi embassy who came to the signing and they were saying they liked the book and they also were saying bad things about Saddam Hussein.

Findakly: They were talking about the harm that he did to the country. I was so shocked that I didn’t know how to respond, because it was shocking to me that somebody from the cultural services of the Iraqi government would ever say anything bad about Saddam Hussein that I didn’t know how to react, so I just sat there nodding my head and saying oh, uh huh. It threw me off so much that I thought maybe they are spies, or this is a trap they are setting for me.

Trondheim: Because for a long time it was impossible say anything bad even if you didn’t live in Iraq any more. You were scared to say anything bad in public.

Findakly: Then of course afterwards I felt ridiculous.

There was also a researcher who contacted my brother. He told my brother that he had learned so much more from reading this book than he had learned from all the other research he had done on Iraq and all the other books he had read.

Where do you think of as “home”?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Findakly: I don’t feel either Iraqi or French. I am sort of a sponge. So for instance when there were all those dictatorships in Latin America, I feel a strong affinity to Latin American and South American culture, because there’s just something there. I listen to a lot of Latin American music and when there were the dictatorships I was protesting in the streets. Whenever I travel anywhere, I feel like anywhere I am I have connections to that place, I am drawn to that place, and I feel at home in that place as much as anywhere else.

Obviously I was deeply nourished by the Iraqi culture that I grew up in at first, and I definitely have a ton of strong connections to the French side of my heritage, but I sort of feel that the fact that I grew up with those elements in my identity makes me neither one or the other but also open to a lot more.

Will you do another comic?

Findakly: I’m not sure. We will see.

Trondheim: She did the book because it became necessary at a certain point, because of her father losing his memory, because of her wanting to tell something to her family because of Daesh invading Mosul. So for another for the motivation to create another book there needs to be a similar drive.

Findakly: In the coming weeks and months I am going to be seeing family members and trying to reconnect with my family, since they have scattered all around the world. We are starting here because there’s a character in the book, Nabla, who lives next door, and Nabla actually lives in San Diego [now]. The first step is that I am going to be spending a week with Nabla here after Comic-Con, and I’m going to be connecting with her and learning her story, and I’m hoping to do the same with my other family members, and after that I’ll see if there’s something in that that needs to be told or if that’s something I will be keeping for myself.

Filed under: All Ages

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT