Announcement and Interview: First Second to Publish ‘Marshmallow and Jordan’

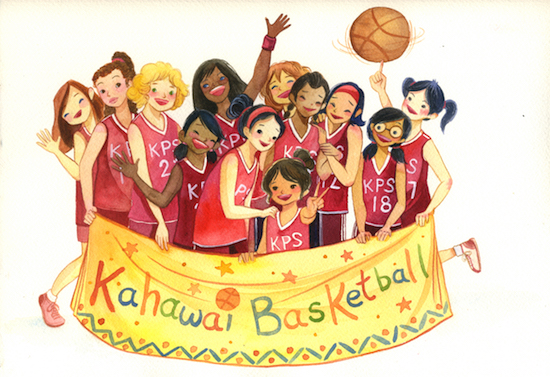

We’ve got big news today: First Second’s announcement of a new middle-grade graphic novel, Marshmallow and Jordan, by newcomer Alina Chau. Chau has a beautiful watercolor style (you can see more of her work at her website), and Marshmallow and Jordan has an intriguing premise:

After a severe car accident, Jordan uses a wheelchair full-time. Newly disabled, her dream to win the basketball championship seems out of reach. But a special friendship with Marshmallow, a magical white elephant, helps Jordan confront her insecurities and discover a new dream.

The book will be out in Winter 2018.

Chau grew up in Hong Kong and has an MFA degree from UCLA. She worked in animation for a decade before turning her hand to book illustration. Here’s what she has to say about Marshmallow and Jordan:

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The story of Marshmallow and Jordan is very close to my heart. As a girl, growing up in Hong Kong with Chinese culture all around me, life at school was challenging. I spoke Chinese with a foreign accent because my parents grew up in Indonesia and our home was a blend of Chinese and Indonesian culture and traditions. Jordan represents the part of my childhood when I learned how to adapt and grow in a world where being different was difficult; Marshmallow represents my childhood perception of my Indonesian roots, which are rich in myths and magic.

We asked Chau to talk a bit more about her background, her art process, and the creation of Marshmallow and Jordan.

In your quote, you talk about the challenges of growing up in Hong Kong as part of a family that was culturally different from those around you. Was there a particular moment that crystallized that for you—either as a child or as an adult?

I realized the differences as soon as I started kindergarten. I spoke Mandarin at home and my parents also spoke Indonesian at home, so though I never learned to speak it, I understand it. When I began school, I discovered everyone else spoke Cantonese. Even though I picked it up quickly, my Cantonese vocabulary was less advanced than other kids. Also, Hong Kong was a British colony at the time, so I was learning English as well and my education was primarily in English. Now, though I speak Mandarin, Cantonese, and English fluidly, my accents in all three languages are a bit mixed up. Language represents a major aspect of a culture, and as I grew older, I learned to accept that a big part of my cultural identity is a melting pot of Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese Chinese, British English, American English, and Indonesian. It’s OK that I don’t fit into each culture 100%; I enjoy that I can still be a part of all these cultures.

An example of this was when the subtle differences of my living habits became more pronounced. In high school, the first time when I went to a restaurant with my friends, things got “interesting.” At home, my family maintained Indonesian eating habits — we ate with fork and knife—and a more Indonesian diet as well. It was embarrassing when my friends discovered that I didn’t know how to use chopsticks and that half the items on the menu were foreign to me.

Growing up, these subtle differences in everyday life made me feel like a bit of a misfit. When I got teased at school, I couldn’t quite express why I was different, because on the surface I looked like other Chinese kids. We had foreign students at school, but their differences were better accepted than mine were, because I was a puzzle. The non-Chinese students were already foreign, but I looked like a regular Chinese kid. It was confusing that I spoke and acted differently than other Chinese kids did.

You also mention the tension between being true to your roots and adapting to the world you live in now. How will that play out in your story?

During most of my childhood, I couldn’t articulate why I felt like a misfit among my peers. When I immigrated to the US, I had to adapt to a new culture and new life. Later I recognized that the feelings I had as a kid mirrored those I experienced when I first moved to the US. In the US, it’s very obvious that I am a minority and different, but growing up in a Chinese society, it was harder to understand feeling isolated, because I looked the same as the other kids and my family looked like any other Chinese family.

When I was younger, I often felt shy about my cultural upbringing. When I was older and had friends of different ethnic backgrounds, I learned to appreciate the uniqueness of my upbringing and cultural identities. With that perspective, it made me realize the importance of sharing multicultural stories.

Marshmallow and Jordan is meant to share a slice of life of a group of middle schoolers living in Bali, Indonesia, who have different religions and ethnicities, and in which friendship troubles and tears may not be caused by any vicious intentions, but between best friends with different backgrounds and culturally-informed assumptions.

Your protagonist, Jordan, uses a wheelchair after a car accident. Have you had any experience with having mobility limitations? What sort of research did you do (or do you plan to do) to ensure this aspect of the story is grounded in reality?

I never experienced mobility limitations myself, but early in the story’s evolution as I realized that the character Jordan is paraplegic, I discussed with a few of my doctor friends what this medical condition would entail, so that I understood what Jordan would realistically be able to perform and achieve. I researched paraplegic athletes and sports, as well as the everyday life of a paraplegic child, which not only included how they move around and perform daily tasks, but also their home set up, etc.

As for the story, I want to focus on Jordan’s psychological struggles and growth. When the story begins, it’s been a few years since Jordan’s accident, so the story won’t focus on her physical recovery. It’s about Jordan’s journey in figuring out how to move forward with her dreams at the same time as surviving her first year in middle-school. To ensure that my portrayal of Jordan’s paraplegia and wheelchair use is conscientiously and accurately represented, I will be working with a sensitivity reader.

How did this story “grow” in your head? Did you start with the characters or the idea, and where did you go from there?

The original story idea started with Marshmallow. I always want to tell my version of the white elephant myth. The white elephant carries a special symbolism in various Southeast Asian cultures. My original version of the story was a fairy tale white elephant children’s picture book idea, but over the years, the plot got more complicated. It started out as a period story with a One Thousand and One Nights sensibility, but evolved into a contemporary middle-school story. The only element that stayed the same throughout all these versions was Marshmallow. He is the key to the story. I don’t want to reveal too much about Marshmallow here, otherwise it could be a spoiler.

Who was the most difficult character to write?

Jordan. I want to capture her emotional and psychological growth believably and with sincerity. Her experiences and emotional arc are very complex. The first year of middle school is a huge adjustment for any kid, but it’s extra tough for Jordan, because Jordan’s new schoolmates tend to stereotype her by her disability before they get to know her. There are not many stories with paraplegic characters; I think it is very important to include people of varying experiences and abilities in stories, especially stories for younger readers. This kind of inclusion also is a visible reminder to children with disabilities that their voice is as precious and valid as others, and their stories can also be cherished and recognized as an integral part of our culture.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

My goal is to depict Jordan authentically so that readers can relate to her life, which is filled with laughter, tears, and drama like any middle school kid, but with an extra layer to the story based on her differing abilities.

What sort of comics did you read when you were growing up? How have they influenced your work?

I read tons of manga, Tintin, Garfield etc.. Oh, and of course Miyazaki, especially My Neighbor Totoro. That’s the biggest inspiration for this book. I want to capture the magic and charm of childhood, and the bittersweet lessons kids learn as they’re growing up. It would make me very happy if a young reader could relate to the kids in the book, and bring the adult readers back childhood memories, both tears and laughter.

How did you create the art—are you actually doing a watercolor for each image? Was that time-consuming?

Yes, I am planning to watercolor the entire graphic novel. I calculated my painting speed and have a general idea of how much time I will need to paint the whole book. I haven’t yet started the coloring process, so I don’t know how I would feel about watercoloring over 200 pages of book yet. For now, I am both very excited and slightly terrified by the idea. In my head, it looks beautiful … so I am going to think positively, with my fingers crossed….

How does your experience in the animation industry inform your graphic novel work?

I worked as an animator and story artist for various major gaming and animation studios. My last production title was story development for Star Wars: The Clone Wars animated TV show. Years of working on a wide variety of productions, from kids title such as Spyros, Bakugan, and iCarly, to adult titles such as Medal Of Honor, God of War, etc.. were a good training in learning different storytelling styles. When I am planning and developing the story for my book, I tend to think in film language. I approached my graphic novel with the same approach as making an animated film, from visual development, to character design, to storyboarding. I feel like making graphic novels is very similar to storyboarding, but with prettier and more polished art. In animation, part of the animator’s job is develop appealing, believable characters by understanding the characters’ motivation and emotional arc. Many of those film storytelling tools have come in handy when developing the story of this book. I also illustrated a few children’s picture books. One of my most recent children’s picture books, The Nian Monster book, written by Andrea Wang, received an APALA Literature Award Honor this year. Illustrating for picture books also helped strengthen my visual storytelling skills and prepared me for this graphic novel.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Interviews, News

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Coretta Scott King Winners

The Ultimate Love Letter to the King of Fruits: We’re Talking Mango Memories with Sita Singh

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

The Tortured Poets Department Poetry Party Part 2: DIY Frames for Your Instant Photos

ADVERTISEMENT

Speaking as an multi-racial person, one can’t equate not fitting in culturally and racially with the experience of having a physical disability.

I’m quite tired of graphic novels being written by people who believe talking with doctors or attending parades is sufficient research to write, with authority, about people with life and cultural experiences far outside of their own. This is it’s own special kind of appropriation (see “Ghosts” by Raina Telgemeier and “The Nameless City” by Faith Erin Hicks). It’s the same as a person who with full hearing writing “El Deafo” because they spoke with deaf kids and a Otolaryngologist.

Speaking as a hearing impaired person, I’d rather there was a book whose author spoke with “deaf kids and a Otolaryngologist” than not have the author write it all.

Check your bitterness barometer!