Review: ‘Spinning’

Spinning

Writer/artist: Tillie Walden

First Second; $17.99

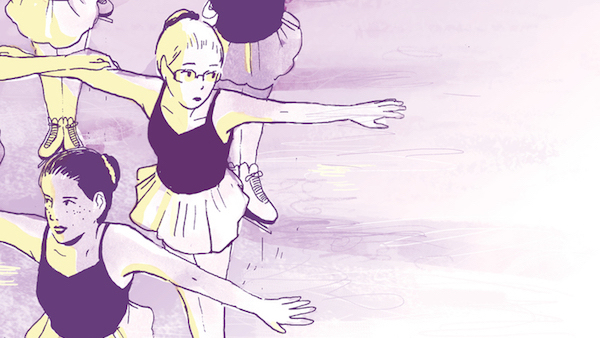

Spinning, 21-year-old cartoonist Tillie Walden’s 400-page graphic memoir, isn’t really about figure skating, although that is the ostensible subject matter. Indeed, few pages go by without a scene set in or around an ice rink, or featuring the protagonist going to or coming from a practice or competition, or talking about skating.

Spinning isn’t really about the difficulty of coming out to one’s family, friends, classmates and teammates either, although doing so proves one of the more dramatic challenges the young skater faces as she searches for her own identity while living so much of her life in a world of artificial femininity and enforced uniformity.

Spinning isn’t really about the difficulty of coming out to one’s family, friends, classmates and teammates either, although doing so proves one of the more dramatic challenges the young skater faces as she searches for her own identity while living so much of her life in a world of artificial femininity and enforced uniformity.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I’m not entirely sure Spinning is about growing up, although it covers over a decade of Walden’s young life and details her coming of age and gradual acceptance of who she really is and her power to control her own destiny.

Rather, while Spinning does indeed cover all of these subjects, I would argue what the book is really about is the feeling of growing up, the slow dawning of autonomy, the chaos of change and the eventual adaptation to it that define the process. The book puts the reader inside that particular maelstrom of emotion, returning adult readers to the state of mind, warning younger readers of what’s to come, and letting adolescents know they’re hardly alone in what they’re experiencing.

Any memoir, prose as well as comics, can detail the events of a life, and the details of Walden’s are certainly interesting and idiosyncratic. Competitive youth figure skating is a weird world, charged with overt, potent symbolism perfect for a coming of age story. And in the years covered, Walden is faced with dramatic situations, on and off the ice, with the “off” ones including being bullied at school, the heart-breaking reactions of her family when she tells them she’s gay, the loss of her first love to that girl’s mother cutting off all contact between the girls, and a sexual assault that is made all the more terrifying by the fact that the attacker doesn’t seem to think he’s doing anything wrong and the young Walden blames herself at the time for what transpired.

What prose can’t do, however, or at least not so well or so immediately, is put the reader into those events. Walden engages in some narration, but much of the story is told organically through the imagery and the dialogue. But the feeling comes from the silent panels, the pauses between beats of dialogue, the expressions on the drawn Walden’s face as she takes in what’s happening around her, the dirty looks of disapproving adults, the staging of moments, both mundane and melodramatic. An emotion can be atomized, rearranged and staged for maximum impact across multiple panels in a comic, so that while Walden can, perhaps, say she feels sad or lonely or alienated in the narration, a reader can read sadness, loneliness and alienation in the tiny, delicately-drawn figure in a huge empty space, the pale white of a somewhat abstracted drawing of a little girl in a void of pre-dawn blackness.

Sure, it’s interesting, and yes, it’s also depressing, a little scary and somewhat hopeful, but, more than anything, it’s affecting and, because of that, effective—almost devastatingly so. It is also a major work from a young artist, one who is all but certain to be a major figure in comics in the years to come.

Filed under: Reviews, Young Adult

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT