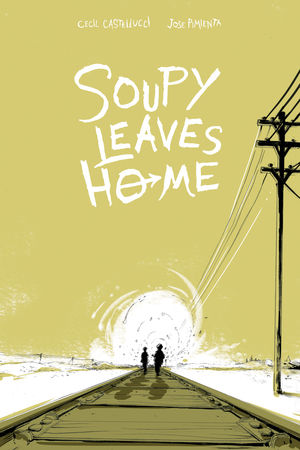

Interview: Cecil Castellucci on ‘Soupy Leaves Home’

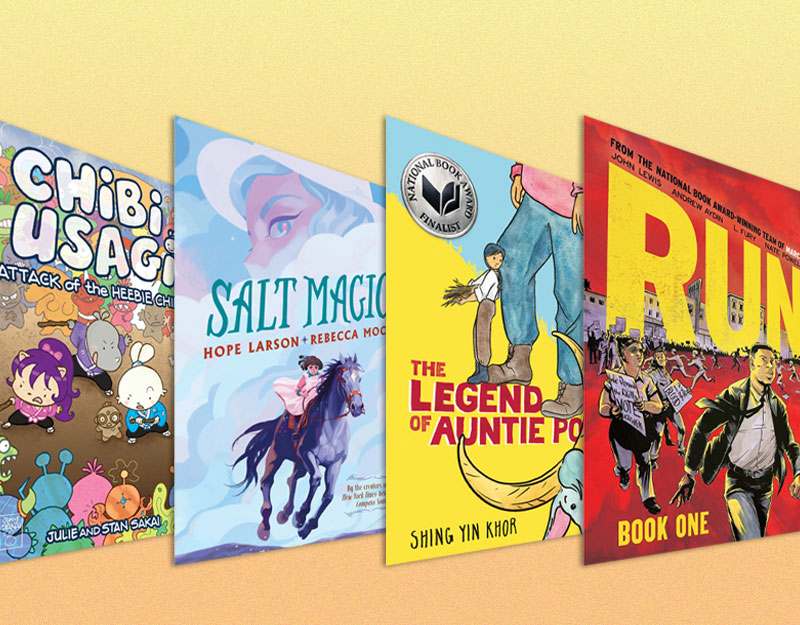

Cecil Castellucci and Jose Pimienta’s Soupy Leaves Home, set during the Depression, is a story about a girl who walks away from an abusive home, disguises herself as a boy, and rides the rails as a hobo. Her companion and protector is Ramshackle, a much older man whose imagination and open-heartedness help her heal and become someone new. Together they journey across the country, sometimes on their own, sometimes in the company of other hoboes. I interviewed Castellucci and Pimienta at Comic-Con in San Diego last year, while the book was still in progress. Now that it is complete, and will be released on April 19, I was happy to have the opportunity to ask Castellucci some more in-depth questions. Before we start, here’s a trailer that will give you a flavor of the book, and we have a short preview at the end of this interview.

Cecil Castellucci and Jose Pimienta’s Soupy Leaves Home, set during the Depression, is a story about a girl who walks away from an abusive home, disguises herself as a boy, and rides the rails as a hobo. Her companion and protector is Ramshackle, a much older man whose imagination and open-heartedness help her heal and become someone new. Together they journey across the country, sometimes on their own, sometimes in the company of other hoboes. I interviewed Castellucci and Pimienta at Comic-Con in San Diego last year, while the book was still in progress. Now that it is complete, and will be released on April 19, I was happy to have the opportunity to ask Castellucci some more in-depth questions. Before we start, here’s a trailer that will give you a flavor of the book, and we have a short preview at the end of this interview.

Which came to you first—the ideas for the characters or the concept of the story?

The characters came first. Someone had posted about hobo names on Facebook and I thought, “Oh, I’d call myself Soupy.” Once I named her it wasn’t too long before I thought about who she was and why she was called Soupy and why she’d left home. And it was a short (train) hop to then coming up with Ramshackle and Tom Cat and Gums and the Professor. Who were these hoboes? How did they get there? Ramshackle, I knew always, was a dreamer, a man before his time. I think I mentioned when we talked in San Diego that I was going through some very dark stuff at the time that I started dreaming up this story, and I think I was looking for a guide who could see the beauty in life that I was unable to see at the time. Ramshackle having that ability and me writing and thinking about him helped me to see things that I was unable to see. Things like hope. I also knew that I wanted it to be about movement and roaming this beautiful land. When I found out that in hobo parlance, “going west” is sometimes a shorthand for dying, I knew that was something to hang a story on.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

What sort of research did you have to do to create the world of Soupy? Was the hobo life something you were already familiar with? Feel free to throw in a fun fact or two that you learned along the way!

I had always known about hoboes. I feel like I saw them very early on in cartoons, in Little Rascals, in Snoopy. I think that there is something about hoboes that captured the imagination, much like beatniks hitting the road. This sense of adventure and travel and trains. There is something romantic about leaving and train travel. But I think seeing the movie The Journey of Natty Gann was probably my first real encounter with hoboes. I loved that movie. Then in film school I saw Sullivan’s Travels. Both of those films have girls who dress up as boys and ride the rails. One thing I learned about that I only had a vague knowledge of was that they had this strict hobo code. It’s kind of a beautiful code. Also, I sort of knew about the hobo signs, but really digging into that and knowing that there was this whole shadow culture that you could either see or not see was really cool. One thing that I did was made a trek to Britt, Iowa, which is where the Hobo Convention happens every year. I didn’t go during the convention, but I went and visited the museum there. Hoboes have been gathering there every August since 1900. Pretty amazing.

Soupy passes as a boy in order to fit in with the hoboes. Were there women hoboes? How essential was it to your story that she live as a boy, as opposed to simply going out and exploring a new world with new people?

There were indeed women and girl hoboes and from my research and from most accounts they pretty much all dressed as boys. It was safer for them that way. Many of them traveled alone, and it just gave them cover to ride incognito and not stand out. It also gave them freedom to work. So it really was an essential part of the story that Pearl becomes a boy named Soupy. It also served a double purpose in this story. Pearl didn’t want to be herself anymore, so it was a reinvention of a sort. To be clear, she doesn’t want to be a boy, but being disguised as a boy gave her the freedom to find her way back to herself.

For a story like this that’s based in a specific historical period, is it easier or harder to tell it as a graphic novel, as opposed to pure prose?

That’s a really interesting question. I think both can work and both have their strengths. I think that this story was best suited to being a comic because Soupy is kind of shut down and a comic book allows you to have silence. It also allows you to have scope and vistas. I love that a comic book can immediately show you how different a time was with its images. Jose’s art is just gorgeous and sweeping at times, and I feel like that is really what it feels like when you think of the romantic elements of the hobo life. America. The land. The rocking of the train on the rails. The endless walking. I also think that the magical-realism elements related to Ramshackle and the way that he sees the world work best visually. I have the great honor of being both a prose writer and a comic book writer, so I try very much to follow which way the story tells me it will best be told. For Soupy Leaves Home it was very much a comic book from the get-go.

Is there anything deliberately anachronistic about this story?

The magical-realism parts with Ramshackle for sure. When he thinks and dreams about the future, we wanted him to be seeing the world that we couldn’t see and that they couldn’t possibly imagine. But for the most part I tried really hard to keep it very much in 1932. For example, Bennington College being newly opened or Pluto just being discovered. That my twenty-first-century feminist views sneak in there a little bit is just a part of telling the story from this vantage point. I know that Jose researched what the trains would look like so that they would be accurate to the times.

There’s a lot of nonverbal storytelling in this story, such as the color shifts and the sequences where people are talking about their memories or their dreams. How had you visualized these as you wrote the story, and how did you communicate with Jose?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

One thing that I love so much about writing comics is that in comics you can have moments of silence. Places where the reader can pause and rest and be quiet with the narrative. That’s the genius of comics. The color stuff was very deliberate and intentional and that was all Jose. He really brought that to the book, and I think it works so well. Jose and I totally communicated and talked during thumbnails, but he really knew what he was doing. For my part, the great thing about working with such a talented artist is that when I get the pages back, I just start throwing out the words. For me the words are the scaffolding to build the world on, to set the mood, to communicate with the artist what the feeling is and then you just delete them so that the story can move from panel to panel unencumbered.

Aside from the leads, who was your favorite character?

I have a real soft spot for Professor Jack. I think of him as this guy who just can’t get a break yet in a Depression-era world, but I have a lot of hope for him that he’s going to find his way. He’s the kind of person who presents himself one way because he’s had to be that way to survive, but if you look at his core, you see his true goodness. I’m also fond of Tom Cat. I think his care for Soupy and return to family is lovely, especially since his friend didn’t get to have that kind of reunion. I’m happy for Tom Cat and his new end-of-life adventure.

How did your experience with the earlier graphic novels you have written influence this one—and how do you think having created Soupy Leaves Home will affect your future work?

For this book I wrote an open script. I had done that before for The Year of the Beasts with Nate Powell and it worked well. I wrote action and dialogue, and he broke it down into pages and panels. This way he got the emotional temperature of the book but could make his own decisions about pacing. When I write for DC Comics (like on Shade, the Changing Girl), I do full script where I break down the page into panels. For this book, I did a mix of the two. I broke down the story by page, but I did not put panels in the page. This allowed me to sort of direct the flow of the story but also allowed for Jose to do panel placement and highlight what he thought was most important. This is also why I was able to throw out a lot of my text. I overwrote those pages, and Jose could pick what was important. It worked pretty well and I think it helps to really have a full collaboration. I think that I will continue in this vein when I’m not doing a monthly. Of course, even when I write a full script, the artist always has full permission to change the panels as they see fit. I think of it all as a guideline.

I know from our conversations that you, like me, like to take the train. Has writing this story changed the way you experience train travel?

I do have a dream that I will take every single train line in America one day. That is just a bigger desire now. I want to do the TransCanada train. And, well, all of them everywhere in the world. I love to write on trains. I think they are very conducive to the dreaming that one needs to come up with a story. I think that there will be more stories with trains in them in my future. So it hasn’t changed the way I experience train travel; it enhanced it.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Interviews, Previews

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT