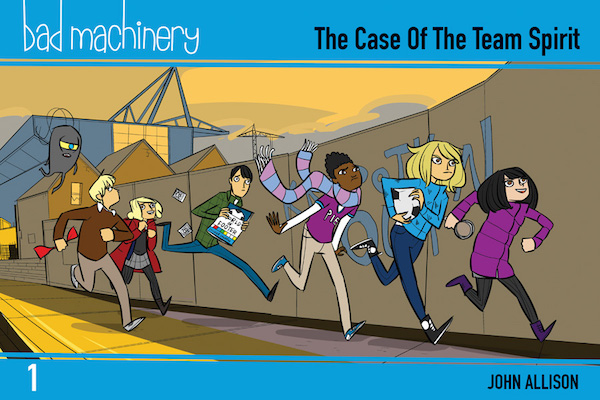

Interview: John Allison on ‘Bad Machinery’

John Allison’s Bad Machinery is a cheeky, funny story about English schoolchildren who solve mysteries, and now it’s coming out in a new, easier-to-read format.

Bad Machinery started out as a webcomic, and you can still read the original in its entirety at Allison’s site (start here, and set aside some time). Then Oni Press started printing it in large, landscape-format books, about 9″ x 12″. That’s a great size for reading at a table, but not so good if you want to carry the book with you—”You can’t put them in a backpack,” as Oni’s managing editor Ari Yarwood pointed out. So starting in March 2017, Oni will publish a smaller edition, still in the landscape format but sized at about 6″ x 9″. The smaller books will have the same content as the large ones, including the extra bits Allison puts in each volume; the only difference is the size. And the price: The large books retail for $19.99, while the first volume of the smaller edition will be closer to $10, and subsequent volumes slightly more. Oni will continue to publish new volumes in the larger format as well.

We took the opportunity to ask Allison a few questions about what goes into making Bad Machinery as well as what he thinks about the new edition.

For readers who are not familiar with Bad Machinery, can you give us a quick elevator pitch?

They’re books about the lives of six archetypal mystery-solving kids (three boys, three girls) in a British town. How do you balance investigating the unknown with growing out of being a carefree kid? In the first book, they’re just turning 12, and in the story I’m working on now (the tenth), it’s the summer before they start to turn 16. They tackle supernatural beasts, aliens, time travel… once, they tackle nothing at all and it all falls apart. There’s a lot to go at there.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I really enjoy Bad Machinery—it’s like the Secret Seven, but with much more edge. I wanted to start by asking what kinds of stories you enjoyed as a kid—books, comics, movies, whatever—and if Bad Machinery reflects any of these.

Pre-teen, I read everything, I’d get the maximum six books from the village library and just steam through them. I read all the Enid Blyton, then so much more besides. I loved sci-fi author Nicholas Fisk, but I can remember picking up books like Hating Alison Ashley by Robin Klein, the sort of book that would now be so violently pink that a ten-year-old boy wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole, and it really sticking with me. We didn’t have a VCR until I was 14 so I didn’t see a lot of movies. I read a lot of Marvel comics, Transformers and superhero stuff. I liked irreverent magazines, and there were a lot of those in the UK in the late eighties—Smash Hits, Zzap!64 (a video game magazine) were the biggest things for me between 11 and 13.

How do you come up with these plots? There seem to be a lot of side trips—as this is a webcomic, I’m wondering if there is a lot of improvisation involved.

The plots are heavily thought through. I begin with a detailed roadmap. There’s improvisation, but it’s along a theme, I still have to get to the end of the song and I know what that is. Working on the web slows down the process of delivery so, writing week to week, I see new opportunities opening up as I go along.

You use supernatural elements in Bad Machinery but you don’t put them in the forefront. Why do you bring in that fantasy element, and why do you choose not to let it dominate?

I want every page to be funny, and the more peril I put in, the closer I veer to swathes of near-dialog-less pages about a sinister wave or a howling beast. That’s fine, but it doesn’t feel like value for money to me. When I read books as a kid, the more hum-drum side of the plot was the more interesting part—what the Famous Five got up to at home, the little personal tussles. I just tried to turn up that aspect of it without turning it into a pure slice-of-life thing.

What sort of changes do you make when moving from the webcomic to the printed book?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The webcomic is dense—six-to-eight-panel pages in a lot of cases, and the scene changes tend to be implied. So when I go to print, there’s some heavy lifting to be done getting the characters from scene to scene and making the book less dense. It’s something I think I’ve got better as as I’ve gone on. And it’s a chance to take a second pass at any art snafus that might have been bugging me in the meantime.

Do you think the print edition is bringing new readers to the webcomic? Why do you continue to make it available online?

I don’t know if the books have fed back into the webcomic—I’m pretty removed from the raw statistics—the books sell, and continue to sell, but I have no idea who is reading them. Social media have pushed webcomics to the side a little bit in the last ten years. Nearly twenty years in webcomics have taught me that adult readers’ relationship with webcomic “merchandise” has almost nothing to do with whether they’ve read it before. But the long and short of it is that making these books is hard, I don’t have time to go out on the road, and the website is a huge billboard for Bad Machinery.

Oni Press is publishing Bad Machinery in a new, smaller edition in addition to the larger ones. Whose decision was it to go this route, and how do you feel about it?

The large format is divisive. They’re great-looking library books. Kids love the big books, adult readers don’t so much, and Bad Machinery has something for both groups. I’ve met readers aged six, and aged 70. I think smaller versions will play well with a large part of that range.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Interviews, Web Comics, Young Adult

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT