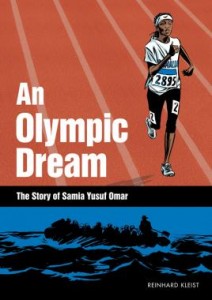

Review: ‘An Olympic Dream: The Story of Samia Yusuf Omar’

An Olympic Dream: The Story of Samia Yusuf Omar

An Olympic Dream: The Story of Samia Yusuf Omar

By Reinhard Kleist

Self Made Hero, $22.95

One of the most inspiring stories to come out of this year’s Olympics is that of swimmer Yusra Mardini, a refugee from Syria who helped rescue a group of refugees in a rubber dinghy by swimming for three hours, with two other women, pulling and pushing the boat to safety.

Reinhard Kleist’s biography of the Somalian runner Samia Usuf Omar is a very similar story, except for the ending: Omar also fled her home country, and the last leg of her journey was in a flimsy boat—but she did not survive the crossing. The closing images of the book are of Omar comforting a crying infant in the raft, saying “Running is like flying,” and then, on the last page, triumphantly winning a race, her words to the child above her: “You’re faster than everyone else. No one can catch you. Then you reach the finish line and you throw your arms up in the air and it’s like… going to heaven.” In an epilogue, we see the Somali runner Abdi Bile pay a tear-filled tribute to her at the 2012 Olympics, intercut with scenes of a larger ship coming to rescue the refugees, hands grasping for a rope, and then, in a final poignant scene, Omar’s patterned headscarf floating on the waves.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Kleist takes some poetic license with this part of the story, as he does in other places. Omar had a Facebook account through which she kept touch with friends and family, but the account has been deleted. He based his story on interviews with people who knew her (including journalist Teresa Krug, who wrote the afterword) and included fictional Facebook posts to help readers keep tabs on Omar throughout her journey. He freely admits that he fictionalized parts of the story, and the Facebook posts read more like exposition than the voice of a 19-year-old, but the story he tells feels solid and very real.

Interestingly, he chooses not to show Omar at the very beginning of her story. Instead, we see her family gathering with others to watch her run in the Beijing Olympics in 2008. Omar, thinner than the others and clad in a bulky T-shirt and leggings, finished last by a large margin, but her pluck in continuing to run to the finish line brought cheers from the crowd. This opening builds a sense of intrigue and also shows that Omar was very much a part of her community, even though she eventually chose to leave it. (The family gathering is fictional, however: Al Jazeera reported that her race wasn’t carried on Somali television.)

Omar’s return from Beijing to her family brings a warm welcome but also plenty of trouble. In Somalia, politics, economics, and the difficulties of living in a war-torn country run by religious police all intertwine to create an impossible situation, especially for someone who has had a taste of life on the outside. Somalia is torn by civil war and in Mogadishu, where Omar lives, the Al-Shabaab militants impose strict religious rule. Omar’s father was shot in the market square, apparently for not following Sharia law (Kleist does not show this happening and only hints at the circumstances). Her mother became a fruit vendor, but the key to the family’s survival is the money Omar’s sister Hodan, who fled the country and lives in Finland, sends home. Omar does her part by caring for Hodan’s children, and she also trains for the 2012 Olympics, hoping to not only run for her own sake but also earn enough from endorsements and sponsorships to support her family. This too, seems impossible: The stadium in Mogadishu where Omar trains is pockmarked with holes, she can’t get a proper diet, and the Al-Shabaab militants harass her, saying women shouldn’t run.

Omar’s journey begins when she moves to Ethiopia in hopes of being able to train there. She stays with her Aunt Mariam, but her plans fall apart almost immediately when the trainer there tells her they have no facilities for women. She and Mariam decide to leave the country and escape to Italy, where Omar hopes to pursue her Olympic dream. Almost immediately, she becomes separated from Mariam, and Kleist follows her solo journey through different stages: Riding in the cargo container of a semi truck, clinging with a crowd of others to the top of a car, languishing for long periods of time while waiting for the smugglers to summon her and her fellow travelers for the next stage of the journey, and finally, boarding the flimsy boat that she hoped would take her to Italy.’

Throughout the book, Kleist uses a deft, brushy line and bold areas of black and white to depict his characters and their settings. He has a real talent for drawing expressive faces but also devotes attention to the settings, which are essential to the story—the pockmarked running track in the Mogadishu stadium, the car piled high with refugees throwing up a cloud of dust in the vast desert, the smugglers smoking hookahs in a dark back room. These visual details draw the reader into the story in a way that mere words could not.

Even if she had made it to Italy, Omar’s dream of a starring role in the London Olympics was probably a long shot. She was chosen for the 2008 games by her government—she didn’t qualify—and Krug suggests in the Al Jazeera story that she couldn’t train with the Ethiopian athletes because her running times weren’t good enough, not because of sexism (Ethiopia does have a women’s team). She also had no promise of help from European trainers. On the other hand, running gave her something to live for—and it had become literally impossible in Somalia.

By necessity, though, Omar’s story is not about the destination but about the journey. While Kleist may have fictionalized some of the personal details, the conditions in Somalia and of her journey are well documented. (Earlier this month, in fact, The Guardian reported that her death had spurred other Somali athletes to advocate for improved conditions.) By telling one person’s story, though, Kleist takes the “refugee situation” out of the hypothetical world of news reports and photos of strangers and makes it personal, showing an engaging, relatable hero as she struggles to fulfill her dreams—and comes to a heartbreaking end.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Reviews

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT