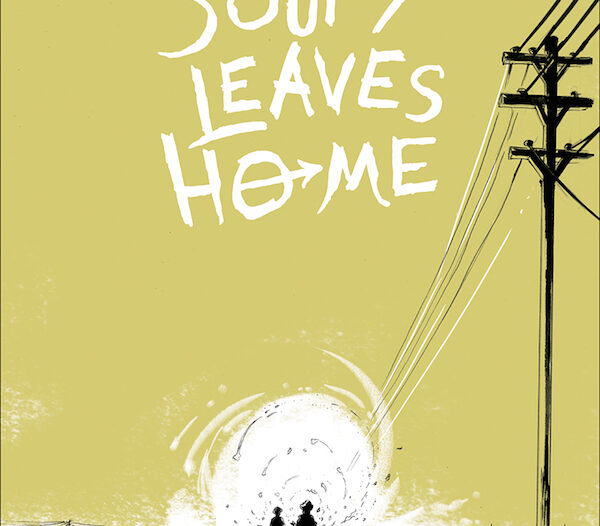

Interview: Cecil Castellucci and Jose Pimienta Hit the Road in ‘Soupy Leaves Home’

Cecil Castellucci, the writer of The Plain Janes, The Year of the Beasts, and Odd Duck, announced her newest project last month: Soupy Leaves Home, a YA graphic novel about a Depression-era girl who runs away from home and completely reinvents herself, disguising herself as a boy and riding the rails as a hobo. I talked to Cecil and artist Jose Pimienta (he goes by “Joe”) about the new project—and about the joys of taking train in modern times!

What is Soupy Leaves Home about?

Cecil: It takes place in 1932, and it’s the story of a girl named Pearl. She’s not in a happy circumstance at home, and she runs away and finds some boy’s clothing and puts them on and is reborn as a boy named Soupy. She meets an old hobo named Ramshackle, and she becomes a hobo and rides the rails across America and figures stuff out.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Where did you get the idea?

Cecil: I was on Facebook and this artist said “My hobo name would be Ramshackle” and I said “My hobo name would be Soupy” and then he was like, “We should write a book” and then I wrote a book.

And Joe, that was you?

Cecil: No, it wasn’t him, it was a different Joe. So I started writing this book. I was actually going through a very, very troubled time, there were big problems, and I couldn’t figure out how to sort of run away from my life. I love train travel, and I just started thinking about what if I could just sort of, just be a hobo for a while and go from place to place and not be myself any more. I felt it was a really good entryway to healing from trauma, which is what I was in the process of doing, so that’s how I came up with it.

Cecil: When I was writing this book, I took the Sunset Limited, which goes from Chicago down through Texas, four days, and I just got the train vibe.

Did you talk to people while you were on the train, and did it influence the book at all?

Cecil: Absolutely. Well, not so much in particular because I was a passenger, I wasn’t hopping a freight train. I’ve done more than the Sunset Limited, I’ve done the Southwest Chief, I’ve done the Lake Shore Limited, the Maple Leaf. The Coast Starlight, the one that goes up to Seattle, that one’s amazing. There was a cinema downstairs and a bar car. That was the most beautiful one. It’s the most gorgeous. I always take the train, and it really is one of my goals to take every train line including the Trans-Canada one.

What I was really struck by was how in the darkness of night, with the rocking of the rails, people will tell you anything. That sort of spirit is definitely in the book, and I feel like hoboes back in the day really they were outside of society. They really had to rely on each other, and they all had a story because there was a reason why they were on the road, and everybody could kind of reinvent themselves. All the hoboes took each other for who they were and how they acted now, not for whatever they left behind. I just fell in love with that.

You do prose novels and graphic novels and hybrids. Why did you decide this one had to be a graphic novel?

Cecil: I think I decided much like Year of the Beasts. When I wrote Year of the Beasts it was the same time period. I have been working on Soupy Leaves Home for eight years. The reason I wrote Year of the Beasts as a hybrid novel is because I felt like when you’re in grief and trauma, and you’re trying to figure stuff out, you don’t have words to articulate how you’re feeling. Prose became too clumsy. And that’s the great thing about writing comics: You can have these moments of silence, you can have these images that articulate everything, and my goodness, Joe’s art in this book—he thinks I’m joking, but when I got the art back I was just like “Oh yeah, we are throwing all of this text out!” We don’t even need words. You can literally read this book with no dialogue at all, and you can understand every single thing that is happening. I cry at the end of this book every time. His art is just absolutely stunning.

Joe, how are you able to translate her words into art?

Joe: First of all, reading the script was very touching. It’s a very sweet story in general. And as someone who has also been a “trouble with identity” teen kind of thing, it hit me on that point where I related a lot to several of the characters, not just Soupy. So when I was reading, it’s one thing to do talking heads, and just be like OK, there’s all this dialogue going on, but to me it’s really important how the characters are feeling throughout whatever interaction is going on or whatever they are going through. That’s what I love about comics so much, that you can actually draw that kind of stuff. Putting that in the forefront, making that a bigger priority—how to translate a really good script, how to tell it visually without having to compromise anything—that’s mostly how I was taking it.

What’s your background?

Joe: I still feel relatively like a very new artist. I have been doing visual development and storyboards and comics for quite a few years, but I switch back and forth so often between doing a book and then taking a year or so off to do nothing but storyboard work, and then dedicating as much time as possible to doing a series of short stories, and then focusing on something else, and then another book lands on my lap, miraculously, so I guess my background is just—I hate to be pompous about it—visual storyteller-narrative person in a variety of different ways.

When you say storyboards, do you mean animation?

Joe: Unfortunately no, because it’s such a fun thing. I have gotten the chance to do storyboards for animation and they are so much fun. Most of my work happens to be for either commercials or live action films, a couple of music videos, things like that. Storyboarding for animation is a whole different thing. It’s a lot more descriptive; you get to do a lot more panels. For a lot of commercial storyboards it’s just can you direct the action and can you set the scene, and then the technical stuff. So storyboards are fun. Comics are just as fun.

What kind of research did you have to do in terms of visual references?

Cecil: [To Joe] I sent you a couple of links.

Joe: Yes, Cecil sent me a couple of links. Honestly, a lot. A lot of photographic reference, a lot of internet searches of how towns looked. This takes place in the 30s, and it’s not just that it takes place in the 30s but it takes place in very specific locations.

In a way that would make it easier.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Joe: Except like, what were rural towns around Chicago back in 1933? It becomes a bit of a challenge to look at little towns instead of just Chicago. One of the first questions I asked Cecil, once I started sinking my teeth in, was where exactly does this story start? Where is the first town? Because I believe the script just said “somewhere in New York,” and that’s a big state.

Cecil: I settled on Albany, right? Or upstate New York.

Joe: Somewhere in New York. That says a lot, and in the 1930s that was very different than it is today. So first the obvious—the outfits, the clothing, the look of towns, the roads, signs, a lot of how the world was in the 1930s, a lot of that kind of research, and everything else. Cecil helped me out with what the hobo signs were like.

Cecil: At one point I saw the pencils for a train towards the end and I said “Hey, I think we need to check this train. It looks too modern.” And then Joe sent me back a picture of the train and it was a 1931 train.

Joe: 1935.

Cecil: And I was like, oh yeah, it’s not too modern, because you forget that the stuff in the 1920s and 30s looked so futuristic, so modern. I appreciated Joe taking very great care with that stuff. Even to the point where we had discussions about what books would be on the bookshelf, because basically, Soupy—Pearl—gets in trouble. She wants to go to college. She wants to apply to be in the first class in Bennington, and her father says no, and that’s what compels her [to run away]. So it’s like, what book gets her in trouble? And then the books that she has later on. Joe was so thoughtful about doing research. It was a really lovely collaboration.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Young Adult

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

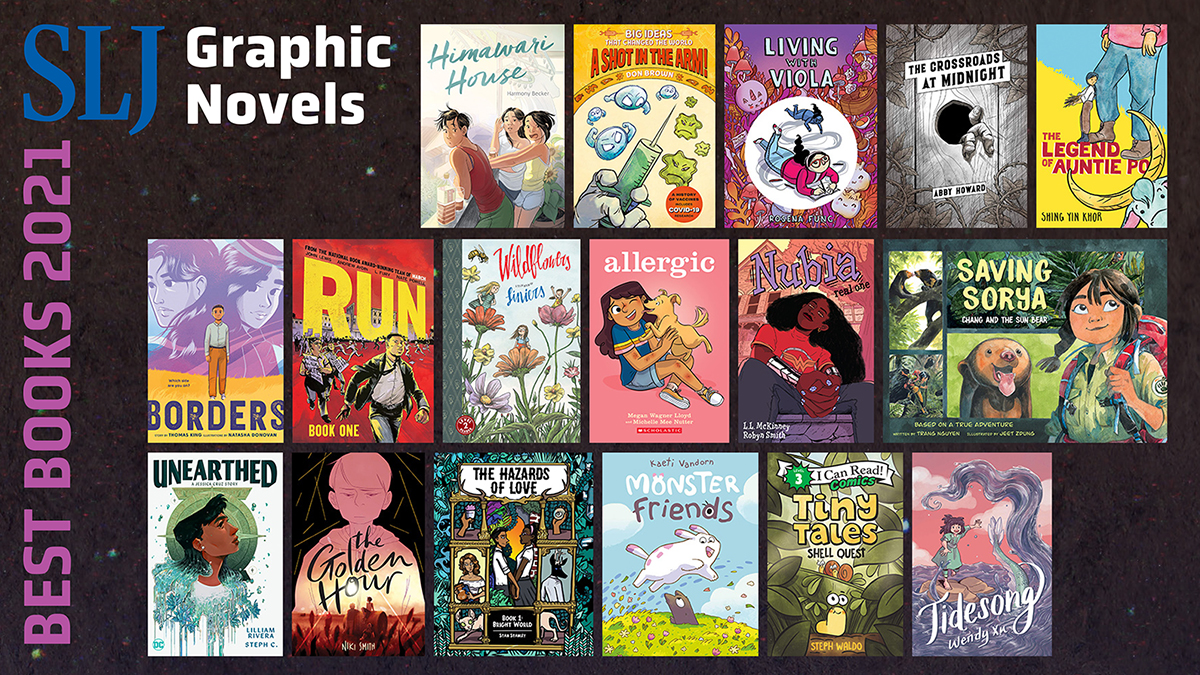

The Ultimate Children’s Book Illustrator Gift Guide 2024

MORE 2025 ALA YMA Predictions! American Indian Youth, Asian/Pacific American Awards, and Schneider Family

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Post-It Note Reviews: Soccer, the Apocalypse, a Reunited Family, Witches, and More!

ADVERTISEMENT