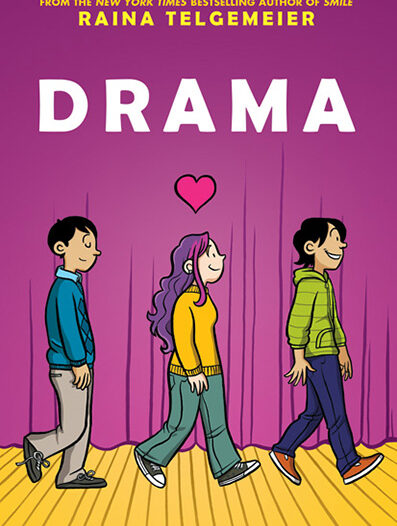

Roundtable: Why all the Drama about ‘Drama’?

Earlier this week, the American Library Association released its list of the most frequently challenged books in America. Last year’s list included Bone and Captain Underpants (which is sort of an honorary comic). This year’s list had three graphic novels: Saga, Persepolis, and Raina Telgemeier’s Drama.

Saga has explicit sexuality, and Persepolis has come under fire for its images of torture. But Drama? The reason cited was “sexually explicit,” but Drama is set in middle school and has no explicit sex—in fact, it has no sex at all, unless you consider a kiss to be “explicit sex.” What’s more, Drama is a great book: YALSA named it one of the top ten Great Graphic Novels for Teens, it won a Stonewall Award, and it was one of the top selling graphic novels in bookstores in 2014, alongside Telgemeier’s other blockbusters, Smile and Sisters. We have recommended it numerous times here at Good Comics for Kids; Esther reviewed it when it first came out and we had a roundtable about it as well.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Why is a book about middle school crushes being challenged, and what does that mean? I asked the bloggers of Good Comics for Kids to share their expertise on book challenge and their thoughts on why Drama would be considered a controversial book. Our participants are Robin Brenner, Teen Librarian at the Brookline (Massachusetts) Public Library; Esther Keller, librarian at JHS 278, Marine Park in Brooklyn, New York; Eva Volin, Supervising Children’s Librarian for the Alameda (California) Free Library; Scott Robins, Children’s Services Specialist at the Don Mills Branch of the Toronto Public Library; and writer, critic, and parent Lori Henderson.

I want to start by putting this into context. People often refer to books being “banned”—can the librarians in the group please clarify what “banned” means in this context and what sort of challenges the list encompasses?

Robin: The definition of ban, from Merriam-Webster, is “to prohibit especially by legal means,” or “to prohibit the use, performance, or distribution of.” In this case the banning isn’t legal, but it is the second—an effort to stop the distribution of a title.

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom annually tracks the formal challenges to titles in library collections (in public libraries, in schools, wherever the library may be). In terms of what challenges are, as the ALA press release states, “A challenge is defined as a formal, written complaint filed with a library or school requesting that a book or other material be restricted or removed because of its content or appropriateness.”

So, this is not a person walking up to a librarian and questioning a title’s appropriateness, but instead an instance of someone putting in writing their objections to a title and requesting its restriction (for example, moving it to closed shelves) or removal from a collection entirely. The Office of Intellectual Freedom relies on libraries to report challenges to them, using a confidential form.

Esther: Robin said it well. Simply put, a ban is actually taking it off the shelf, and a challenge is a complaint. But in this case, as Robin pointed out, the complaint has to be a formal one.

Does it encompass both school and public libraries? Do you see a difference between the two in terms of what sort of books they would be expected to have in their collection?

Robin: The reported challenges come from any library, so school and public libraries are included. Anecdotally, I hear of more titles being challenged in school collections, but public libraries get their fair share too. In terms of what is collected in each, there are obvious differences in age ranges covered. School collections are also tied much more to curriculum requirements. In terms of content, though, there can be a wide range, depending on the local community and range of any collection. A high school library and a public library teen collection will have different titles but share many. A public library can usually collect with the idea that their readers can also venture to the children’s or adult collections to find more titles, while a high school library has to collect everything a student needs, and thus may have more specific adult titles (think summer reading list titles and classics).

Esther: I believe this includes all libraries. So it would even include universities, though I don’t know how often a challenge would occur at that level. Over the years, as I’ve followed the ALA list, I have noticed that many titles on the list are for children and teens.

One more general question: Do you have any idea how many challenges a book would have to get to make the list? Five or 500? And are these formal challenges, or do informal challenges count?

Robin: The challenges reported in 2014 total 311, and I would hazard a guess that the top challenged titles would be, perhaps, 10-20 challenges? I’m not at all certain of that, though!

These are formal challenges—informal challenges are not counted. Most librarians take it as a given that there are more challenges than officially reported, both formal and informal. These reported instances do offer a decent representation of which titles are challenged and why. I believe most librarians deal far more often with informal challenges—when someone just walks up with a book and asks about why that title is in the Teen Room or why it’s in the Children’s Room when it has content they think is inappropriate for the age range. These may also be external (i.e. a patron of the library brings up a challenge) or internal (i.e. someone on the library staff brings up a challenge). The majority of the time, a bit of explanation about the age range of the collection and what a library collects clears up any confusion or concern. The challenges tracked by the OIF are more serious in that they are written requests and require official review.

Esther: As Robin stated, these are only formal challenges that are counted and only challenges that are reported. I had a very uncomfortable challenge in 2006. The book was eventually put back on the shelf, but I never reported it to the ALA office, though I did seek out help from the folks on YALSA-BK (a list-serv sponsored by ALA’s YALSA division for anyone interested in working with young adults and young adult literature). And last year, I had a parent rant at me about a title. But after she yelled at me for what seemed like forever, she didn’t take the matter further. I did notify my principal and assistant principal at the time, but the parent had other concerns and was appeased when the child’s class was changed. I didn’t hear about it again, and no one even asked me the title of the book. Again, I never reported the incident to the ALA office. So when you consider challenges and complaints, consider how many go unreported.

Eva: Yep, I get at least one challenge every other year or so. But rarely does one get “officially” challenged in writing. Usually it’s handled verbally at the reference desk.

Robin: The other aspect to note about challenges to library collections is that sometimes, and often when you see a challenge in the news, the challenger goes around the library’s staff and established reevaluation procedures (such as a committee reviewing a title) and challenges the title in public, through telling their story to the media or bringing in local politicians. This often sidesteps the procedures most libraries have in place to consider challenges and makes for a more attractive news story. Some are reported much more after reconsideration has happened, and the committee decides to retain the challenged title, and the original challengers take the case either out to the public or to a higher political position.

OK, let’s throw it open to everyone. Why are people challenging Drama and what do you think of that? The book was published in 2012, so why do you think people are challenging it now?

Robin: I’d say folks have been challenging it from the beginning, but given Raina Telgemeier’s rising popularity and significant exposure during this past year, with profiles in the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and the Washington Post, it’s no surprise that challenges to her works have risen in number. The more popular something is, the more press you can get by challenging it. The Harry Potter series remains one of the most challenged series partly because it was so popular that it was seen as a greater negative influence by those bringing the challenges. A similar series, His Dark Materials, by Philip Pullman, had much more content that might invite a challenge but wasn’t significantly challenged until years after the series concluded precisely because it had never hit the level of Harry Potter.

Esther: I wasn’t shocked to see Drama on the list. I was just shocked to see why it was challenged. There is nothing explicit in this book. I do believe that because characters openly admit to being gay, the book has been challenged. But it was such a non-issue.

Eva: People have been fussing about the gay characters in Drama since it was published. You only have to look at the date stamps on the Amazon reviews to see that. I suspect it just took longer for the reported challenges to hit critical mass. As Robin mentioned, the controversy surrounding His Dark Materials was always there, but objectors didn’t get loud until the movie was announced.

Scott: We are finally starting to see an effort on the part of creators and publishers to tell stories that involve LGBT characters in middle grade fiction. This is huge considering that LGBT characters are still challenged in YA books. As the representation starts to trickle down to the younger set, we’re going to see knee-jerk reactions from people opposed to this kind of depiction in younger fiction. We have seen major social and political change when it comes to LGBT rights in the past five years, and people are charged on both sides of the issue. With a push on one side, there’s almost guaranteed a push from the other side, and I think the challenges to Drama are just that.

One of the objections raised in reviews on Amazon is that the cover material and blurb don’t mention that there are gay characters in the book. That’s probably because Raina treats being gay as a normal part of life, not something exceptional, and it’s a part of the story but by no means the most important part. Do you think that aspect of the book should have been called out specifically in the promotional material?

Robin: No. The story relies on the slow realization of the orientation of the characters, and putting it in the promotional material or on the back of the book would spoil the plot. Anyone concerned with content can read reviews or read the title themselves before they allow their child to read it. I did a check over at Common Sense Media, and they have a good summary there as well as information on content. I was intrigued to note that at that site, parents deem the book appropriate for 14 and up while the kids deem it ok for 11 and up.

Esther: Not at all. Publishers can’t be expected to put everything in the promotional material. As someone who’s children are starting to read (on their own as opposed to be read to) and a parent who has strong religious beliefs, it’s my job to pre-read or read reviews. I went back to my own review of Drama on Good Comics for Kids, and I mentioned that there are characters wondering about their sexual identity. I assume it was mentioned in most reviews. But as I wrote in the review: “and today’s issues aren’t ignored, though they’re not actually issues in the book, such as characters coming to terms with their sexual identity.” It was such a non-issue, that I remember struggling how to include it in my review. It wasn’t even a main plot point. I just knew that this was something parents and librarians, who don’t always get to pre-read every title, would want to know.

Robin: This is a common reason for titles to be challenged: Some adults believe that sexual identity, and any discussion of homosexuality, is automatically mature content. As is always true, children’s and teen books are the most frequently challenged titles precisely because someone believes the content is inappropriate for the intended audience.

Eva: How often is heteronormativity disclosed in a review? Or that a character is Caucasian? Cover material and blurbs are not the same as allergen labeling.

Robin: Agreed, Eva! At this point, when it comes to sexuality and gender identity, I’m in favor of the idea that there should be no more defaults. Whatever a person (or a character) eventually identifies as is their business. They can make that public when they’re ready, but at this point, I never assume anything until a person tells me.

Lori: No, it shouldn’t because homosexuality should be treated like it’s a part of everyday life, because it is, and kids need to see that. Too many kids who start to discover they might be different before they become teenagers, or even start middle school, still feel that there is something wrong with them because they are not heteronormative, and that is just not right.

Another comment worth noting is that while the book is about middle schoolers, the reading level is 2.6 and most of the readers are probably younger than middle school—my niece is devouring Smile right now, and she’s in third grade. How do you think the age of the readers figures into this debate?

Robin: First, don’t get me started on reading levels and how they don’t function for graphic novels as a format. I hazard that parents decided Raina’s other books are fine for elementary school readers, even though Raina’s memoirs are also covering the period when she was in middle school, and didn’t understand that Drama is both fiction and included middle school romance. As the snarkier reviews on Amazon point out, however, there is heterosexuality in there too, so it’s not romance they are objecting to, but the homosexuality. If we have titles that look into adolescence for middle schoolers, then sexual orientation will be be a part of that discussion as it reflects reality. It’s up to the parents and adults in a child’s life to pay attention if they are concerned about content, and reviews and a bit of googling will help them out in that regard. Challenges, of course, aren’t about what your individual reader picks up, but wanting to keep that title from any young reader in your community.

Esther: Yes the title has a low Lexile score, but so does Lord of the Flies. Reading levels measure things like sentence length and syllables. Lord of the Flies has a Lexile of 770L, which is actually a lower lexile score than the Harry Potter books (which are about 880L). I love the Harry Potter books, but by no means are they more complex than Lord of the Flies. And John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men has a lexile of 660L. So according to this site (go all the way to the last page of this pdf), students in grades 2-3 should be reading Of Mice and Men.

The bottom line is that if parents and educators judge by Lexile scores or other similar devices, they aren’t considering content and complexity of ideas. There’s more to reading than word length and sentence length. (I have lots of fun on Lexile.com when I get started on this tirade.) If you look at Scholastic’s Teacher Store, it clearly lists the title for Grades 6-8.

Lori: I think the age of the readers is the whole point of the debate. Parents are upset not only that their children are being exposed to homosexual characters in a book they don’t think should even be talking about it, but a lot of the children are coming to ask them about it. Several of the one-star comments mention their child coming to them with questions, like a book shouldn’t stimulate a child to want to know, or a child should question what they are reading. Any book that does that should be seen more, not less.

Scholastic is a children’s publisher, and I’m sure their reputation for wholesomeness is important to them. They are standing by the book, as they did with Bone. What do you see as the risks and rewards of having a book challenged, from the point of view of the publisher and the creator?

Esther: In this day and age, I actually believe that a book challenge is good for book sales. I don’t think Scholastic or any other publisher that has a book challenge really has to worry. It’s a small number of people who are targeting these books. They are loud. They are vocal. And they should not be ignored, because that’s how we lose our freedoms, by ignoring those who come and try to quash it. But as for book sales, I don’t think they need to worry.

I think we all, as librarians and critics, believe that people should be exposed to as many ideas as possible, but would you support the inclusion of a book critical of homosexuality in a school or public library collection?

Robin: We do have such books in our public library. That’s part of having a rounded collection. Much of a library’s collection is determined by the local community, so it will depend on whether there’s demand and requests for such titles, but if a library sticks to the ideals of freedom of access, then yes, they will have titles that are critical.

Esther: I think people need to expose themselves to what they are comfortable with. I don’t believe that as a librarian I should be telling anyone what they should read. I only offer them a selection of what they can read. That said, a library is for many and all people. Libraries are for a diverse population. A library should reflect its community. All facets of its community. And no one should come and say, “because I don’t believe that you should read this book, no one should read this book.” If I choose to stay away from a title, then I choose to stay away from it. I don’t have the right to tell anyone else what to do (except my own children).

Eva: What Robin and Esther said. My job is to collect as many books on as many subjects as possible. It is the job of the parents and guardians to decide which of those books are right for their families.

Scott: If it was well reviewed by a reputable source, absolutely!

Robin: Scott’s point about reviews is also important—we librarians collect titles that are reviewed well in library and educational journals. So that will also be a part of any collection’s balance as well.

Lori: Yes. Including such a book does not automatically mean endorsement. To understand a social issue as complex as LGBT, having more information will help people make better informed decisions. Knowing why someone thinks something can help others understand or counter their position.

Filed under: Roundtables, Young Adult

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

As a parent of a second grader, I absolutely have a problem with the book, Drama, being in the elementary school library. Also, the way this school goes about checking out books from the school library totally blocks me,as a parent, to check out the book to see if it’s appropriate or not as they make the kids immediately read the book they check out for 30 minutes. Then, when they finish the book, they take a comprehension test on the book. Like a person stated, scholastic lists it as a grade 6-8 book. My child, after reading some of the book, Drama, stopped reading it and asked to choose a different book. They told her she had to read that book. Also implemented that they were to read the books from the elementary library even if they had a book from home they were reading and halfway finished with. Makes no sense to me if they want them to have comprehension tests to have them start a different book before they finished the book they were reading.

Why would you have a problem with the book it’s self, why can’t you just have problem with the school and it’s curriculum and when it chooses to give it children certain literature?

i am in 7th grade and i read this book in 6th. I LOVE IT. as i am part of that community, it is good to see people writing about LGBTQ people

I’m currently in 6th grade and I LOVE this book. I read it in 4th grade and it’s one of my favorite books.

Why do you have a problem with this book this is an amazing book just because there are lgbt themes doesn’t mean it will “turn my kid gay”