Interview: Danica Novgorodoff on ‘The Undertaking of Lily Chen’

In 2007, artist Danica Novgorodoff was reading through an issue of The Economist magazine when she came across an article about the persistence of the tradition of “ghost marriages” in China—apparently, when some young unmarried men die early, their family members will try to secure a so-called “corpse bride” to bury with them, so that the deceased won’t have to spend eternity alone.

In 2007, artist Danica Novgorodoff was reading through an issue of The Economist magazine when she came across an article about the persistence of the tradition of “ghost marriages” in China—apparently, when some young unmarried men die early, their family members will try to secure a so-called “corpse bride” to bury with them, so that the deceased won’t have to spend eternity alone.

The article noted that while there were respectable, paid professionals who could play matchmaker in such cases, a black market had sprung up for corpse brides, which could be taken from hospital morgues, stolen from fresh graves, or created by murdering a living woman, killed specifically to fill half of that grave.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

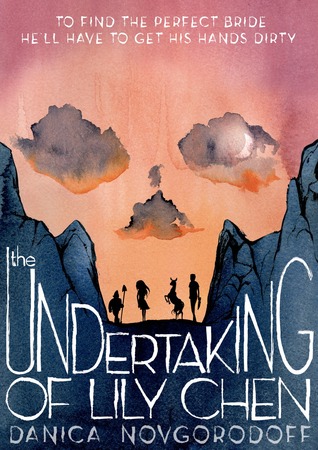

A little traveling, a lot of thinking, and a great deal of writing and drawing later, and Novgorodoff had produced The Undertaking of Lily Chen, a graphic novel in which a paragraph or so of that article runs on the front page.

It’s about Deshi, whose older brother dies in unfortunate circumstances that lead he and his parents to believe Deshi was responsible for the death.Deshi’s parents charge him with securing a corpse bride for his brother, and after some misadventures, Deshi meets Lily, a naive country girl who had just run away from home and fallen into Deshi’s orbit. Should Deshi do the “right thing,” and kill her to bury with his dead brother? Or should he do the right thing and spare her, doing what he can to rescue her from her own dire straits?

That’s the conflict at the center of The Undertaking of Lily Chen, which features a love triangle between a living man, a living woman and a dead man. We spoke with Novgorodoff, whose previous major comics work consisted of Slow Storm, which she similarly wrote and drew, and Refresh, Refresh, which she drew.

GC4K: Do you remember how you first came across the article, and what your initial reaction was? Did you have a cartoon lightbulb-going-off-over-your-head sort of moment, where you knew immediately that there was a graphic novel in there somewhere?

Danica Novgorodoff: I subscribe to The Economist, and usually skim over it for a general sense of world events and for any particularly interesting (non-finance) stories—and yes, I immediately thought this would be a great premise for a work of fiction. I excitedly summarized the article to my editor the next day, and a mere six years later we published the graphic novel.

GC4K: What is really striking about the persistence of the practice is the sort of clash between the superstition and the modern, 21st century it persists in. And one of the more fascinating elements of your story was that while it is clear it’s taking place in the present—when we first meet Deshi he’s guarding fighter jets, after all—much of the story seems like it could have occurred at various points in the distant past. That is, we see more donkeys and horses than cars, knives rather than guns, and there’s talk of arranged marriages and, of course, the ghost marriage. Did you find yourself having to emphasize that contrast at all, or did it just come naturally?

Novgorodoff: Before I had ever heard of ghost marriages, I went to China for the first time to travel for two weeks with a friend from Hong Kong. Part of what really fascinated me about the landscape was the striking contrast between the old and the new—suburban high rises rearing up on the horizon of a barren, windswept landscape; giant infrastructure projects between sacred mountains; tower cranes in front of thousands of year old temples.

So that contrast was already on my mind, along with some knowledge of the strife between urban, modern China and rural, more traditional China. I think that struggle between antiquated and contemporary culture is present in every age and society, but it’s particularly obvious in China today because of its rapid political and economic development.

The clash between the ancient ghost marriage custom and the desires and dreams of the young characters in my book points to a larger question—how to honor the old but strive for the new?

GC4K: From a far enough removed perspective, the practice of ghost weddings and corpse brides can seem ridiculous; it will likely strike most of your readers as somewhere between silly and crazy. How sympathetic are you to the point-of-view of Deshi’s parents, and the real people who hold these beliefs? Even if you yourself don’t believe in the need for ghost marriages, can you see where those who do might be coming from?

Novgorodoff: While I would certainly not go so far as to rob a grave or murder a girl, I think it’s beautiful, in a way, that the dead boy’s parents would want to send him into the next world at peace, and not lonely. Everyone is afraid of dying alone, and perhaps this custom softens the fear and grief by reassuring the parents that their son’s tragic death finds some comfort in the end.

Like Lily, I believe that most funeral traditions are performed for the sake of the living, to help the friends and family of the deceased deal with their loss and sadness. Performing a ghost marriage in order to send someone into the afterlife happy and loved doesn’t seem so different from performing last rites so as to send someone into the afterlife happily absolved of sins.

Except, of course, if you can’t find the right corpse bride…that’s a bit trickier than finding a priest.

GC4K: Did the book require much in the way of research? You mentioned having visited China before. While you were there, did you visit the sorts of rural places in which much of the book is set?

Novgorodoff: I’ve been to China twice—the first time I went to visit a friend who lived in Hong Kong, and I had no plans for working on a project based on the trip. But the visit inspired many of the scenes in the book. It was not long after returning to the U.S. that I discovered the article about ghost marriages in The Economist. I returned to China a couple years later to do more specific research, and particularly to find a place to set the story. I ended up combining several different places (the mining villages of northern Shanxi province, a walled city in central Shanxi, and the mountain landscapes of southern Shanxi), and used the hundreds of photos I took as reference material for my drawings.

GC4K: Can you tell us a little bit about how the book was made? Do you write a full script and then set about breaking it into pages and panels, and then drawing and painting? Or do you “write” verbally and visually simultaneously, sketching out the story?

Novgordoff: Aside from the imagery in my head, I start with the text. I worked on writing the story over the course of almost two years before I actually started drawing pages of the book. The drawing element is so labor intensive that I prefer to have the story well mapped out before I begin creating artwork, lest I spend months drawing images that will later be edited out or redone to fit narrative changes. After the writing, I did character sketches and then jumped into drawing the story.

GC4K: Can you tell us a little bit about your character design? It’s very distinctive, and the characters in this book look much looser, more exaggerated and, in many cases, more comical than the characters in your previous works. How did you settle on the look of your characters in general and on the precise depictions of various characters?

Novgorodoff: In my two previous books, I used real people as models for my characters and photographed their faces from every angle as reference material. I started doing that for this project—even found and photographed models—but then decided that the story needed a new visual language, and perhaps one that hinted at a more Asian/manga style.

I went through several rounds of sketches of the main character, Deshi, pushing myself to simplify and exaggerate in each new set. It wasn’t what I was accustomed to and wasn’t comfortable at first. I looked to other cartooning and animation styles for inspiration—The Triplets of Belleville, Coraline, Hayao Miyazaki’s films, Tim Burton’s drawings, even some Disney characters.

GC4K: Were there any character designs you struggled with? Did you find yourself questioning, for example, if Deshi was handsome enough, or if Lily’s father or the grave robber were scary enough?

Novgorodoff: I actually did struggle with Lily’s character design. I wanted her to be attractive, but without resorting to long legs and big breasts. I wanted her to look like a pretty girl from a rural village, not a supermodel or superhero. That said, I wanted her personality to really show through in her character design; she’s sassy, stubborn, gregarious, and willful. Believe it or not, Lily’s body language was inspired by Daisy Duck.

Mr. Song, the grave robber, also took a while to develop. I wanted him to be strong but shifty, dangerous but charming. I ended up finding the teardrop shape of his head by trial and error, and his body type and demeanor was inspired by drawings of horsemen in ancient Chinese scroll paintings.

GC4K: There’s a pretty sharp contrast between the loose, cartoony look of the characters and the very painterly look of the backgrounds and nature, as if we see comic book characters moving through Asian art. Was that a decision you made purely to evoke the particular setting of the story?

Novgorodoff: Yes, I always think of place as a major player in my books. The landscape has to have its own personality. Part of my interest in making the graphic novel was my love of traditional Chinese brush painting, and I wanted my landscapes to reference that tradition. I drew the characters with a very small detail brush rather than a pen so that the figurative linework would retain that calligraphic feel, even though it is distinct from the broader, more painterly backgrounds.

Also, the juxtaposition of the painterly backgrounds and the flat, graphic characters is another element that I hope points to the contrast between the ancient (ancient mountains, ancient customs, ancient scroll paintings) and the contemporary (contemporary infrastructure and development, contemporary values, contemporary cartooning styles).

GC4K: The evocation of the brother’s ghost was similarly very serious in tone compared to the other elements of the story. Did you want those moments to have perhaps a little more gravity, or is that simply down to the way the paint moves on the paper when going for a ghostly effect?

Novgorodoff: Yes, I wanted to convey the feeling that Deshi is being haunted by his brother’s ghost (or by his own grief, or his parents’ demands of him) and felt I needed a more abstract, ethereal sort of imagery to communicate that. I wanted the story to flow between moments of gravity and moments of humor, between the action plot and the love plot, between the gritty and the dreamlike.

GC4K: As a reader, there’s some tension regarding whether or not Deshi will go through with killing Lily, and he seems to try on at least two occasions—once being literally tripped up, the other time having what was meant to be a stranglehold turning into a caress. Did you know all along that Deshi would never be able to kill Lily, or did you consider different directions in which to take the story while writing it?

Novgorodoff: Although I considered many different directions and many different ways that Lily might die in the end, I never believed Deshi would be the one to do it. In fact, I rewrote the ending several times, with results ranging from everyone dies to no one dies.

GC4K: How far into the process were you when the title presented itself?

Novgorodoff: I was pretty far along—I had a working title from the very beginning that ended up making no sense in the final story. So after I gave up on that early title (kill your darlings) I spent a long time searching for the right title.

GC4K: When you were working on this, and when you’ve worked on comics in the past, how conscious were you of your audiences, and the manner in which you address them? I ask because First Second has a reputation for producing Young Adult works, and I’m talking to you on behalf of Good Comics For Kids. Do things like who might be reading, and what might or might not be appropriate for certain age groups factor into your decision making when it comes to your storytelling choices?

Novgorodoff: No, I really don’t think about it while I’m writing. I write for myself, and for what I myself would like to read. But I can certainly see how this might be considered a Young Adult book, since the main characters are in their late teens and early twenties, and it is very much a tale of first love, breaking away from stifling familial expectations, and finding one’s own way in the world.

Filed under: Interviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT