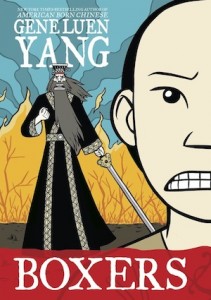

Roundtable: Boxers & Saints

Gene Luen Yang’s two-volume set Boxers & Saints is one of the most talked-about books of the year—the internet is dotted with reviews of the book and interviews with Yang—and when we started talking among ourselves, we quickly realized that we all had plenty to say—and we didn’t always agree. So we decided to put our discussion into a roundtable format. I asked the questions, and then Michael May, Lori Henderson, Mike Pawuk, Esther Keller, and Robin Brenner chimed in with their answers. Feel free to add your own opinions in the comments!

I think the first question is whether this is a good choice for kids. It’s not really being marketed as a YA title, but the rating is 12 and up. In terms of storytelling and the concepts that are explored, who do you think is the best audience for this?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Michael: I feel like Yang’s art style will always skew his work a little younger, or at least give people the perception that it’s geared towards kids. That’s not to say that Boxers & Saints is inappropriate for pre-teens, but it does cover some provocative, dark material and parents should be aware of that. The 12+ rating sounds about right to me, but I know some thoughtful kids who are younger than that and I’d love to hear their ideas after reading these books. I would love for something like this to be curriculum in my son’s school.

Lori: Having just had a daughter go through middle school, I can say the concepts are right in line with what they learn in social studies. They aren’t spared dark material as both the Holocaust and U.S. internment camps are covered, so I can easily see the Boxer Rebellion getting some time. So since it can be part of class material, I do think tweens can handle it. I don’t know if I’d say they were the best audience, but I do think it’s appropriate.

Mike: I agree too. 12+ does sound appropriate since at that age they’re introduced to other dark subject matter in recent history.

Esther: This is a very “heavy” title. What I mean is that that the themes and events are difficult to read about. They were for me. But I think children can handle it. I have no qualms about adding this to my library’s collection, and while it isn’t a direct tie-in with the social studies curriculum taught in middle school, like Lori said, this isn’t any more difficult than reading than reading a title like Maus or Take What You Can Carry, which deals with the Japanese internment. These are truthful renderings of very dark periods of history.

Robin: I agree with what everyone else has said. I certainly had no qualms adding it to my public library’s teen collection (where we serve 7th to 12th graders). I think of the title as challenging in terms of the subject and the subtlety in Yang’s angle of showing a conflict from both sides, but I also don’t think it is any less challenging than prose titles like The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (a book my 12 to 13 year olds love.)

What did you like best about the books?

Michael: The notion that there are multiple sides to any conflict. Yang does a brilliant job of presenting both of the major viewpoints in a way that judges neither of them but lets them stand in contrast to each other. It creates the impression that there are no “right” and “wrong” sides in war, but that both are made up of flawed people with complicated, sometimes inconsistent motives. That’s such an important lesson to learn no matter what your age.

Mike: Definitely agree with Michael on this one. There are two sides to every story.

Esther: I enjoyed the other side of the story. It showed that life has many grey areas. It really added another perspective.

Lori: I liked that the reasons for the conflict weren’t romanticized in anyway. Both sides were portrayed realistically, warts and all, making, as Michael said, that there is no right or wrong side, but leaving it to the reader to decide who to sympathize with on their own.

Robin: I think my favorite part was not only the structure which shows both sides, but how carefully Yang showed the struggle with faith. By faith, I don’t necessarily mean any particular religious path, but with the idea of commitment to a belief and how that can be repeatedly challenged and reaffirmed. He provides a way in to the spiritual and the supernatural with the appearances of the Chinese gods and Guan Yin and the visions of Joan of Arc, which is a parallel a lot of young readers may not have encountered before.

What did you like least?

Michael: I struggled with the supernatural elements. I get why they’re there and it totally works from a storytelling perspective, but it did get in the way of my identifying with the characters when I was constantly wondering if they were insane, literally being possessed, or just had very convincing imaginations.

Esther: Not that the violence was overdone for the title, but the violence bothered me. This isn’t a period in history that I know all that much about. It seems like a very brief part of the history curriculum I may have covered in social studies while I was in school. The realization that this was what it was like made me very sad.

Brigid: I agree about the violence. When there is so much of it, I think the effect is decreased. Seeing Red Lantern’s head on a stick was moving; seeing a bunch of anonymous soldiers get run through with swords was not.

Robin: I didn’t find the balance of the violence off, myself. I think the escalation of violence felt true. The shattering aspect of the final act in Saints (and as part of Boxers) was in no way lessened by the understanding that it was a part of a larger wave of violence, and I think placing it within that context emphasizes that every death is a world extinguished, a whole story lost. I knew very little about the Boxer Rebellion (except, embarrassingly to admit, for references in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer TV show), but I certainly felt the pull of the personal stories and was inspired to do more research to understand the historical conflict.

What did you think about the two-volume format? Do you think reading one of these books on its own is a satisfying experience? Also, did anyone not read Boxers first?

Michael: I love the two-volume format. It’s my favorite thing about the project. Reading one volume could absolutely be satisfying, but reading the other enriches the experience. Having said that, I read Boxers first and don’t know what it would be like to just read Saints. There may have been some world-building done in Boxers that I took for granted when I got to the other book.

Lori: I also liked the two volume format. Each volume told a complete story, but reading both gives an enhanced experience. I read Boxers first, mostly because I’m OCD that way. Being the longer of the two volumes, I think Boxers gives the full context of the story and is better off read first.

Esther: While each volume told a complete story, it’s a shame to separate them into two separate volumes. From a seller’s point of view, it seems like they’re being sold together. As a librarian, I’m not sure how I would shelve it. And to separate it would mean losing part of the meaning. While each story is complete, it’s more complete, and has more meaning, if you read both stories.

Robin: I definitely like the two volume format as a reading experience—I’m a big fan of stories that become more complex and enriched with the revelations of a companion volume. I did read Boxers first, so I can’t speak to how Saints might have read without that context. As I had pre-ordered the set, my catalogers automatically split the two volumes out of the box set to circulate, and I admit I’m a bit sad they aren’t circulating together as a unit. At the same time, I’ll be curious to talk to readers who start with one or the other, and whether they are planning or compelled to read the other volume.

Brigid: I really enjoyed the way the two volumes intertwined. I had several “Aha!” moments in Saints where I got another view of something that happened in Boxers and suddenly it made more sense. Because of that, though, separating the story into two volumes also means that a reader who only finds one book will be missing important information about the story. Perhaps there’s a combined volume on the way that would resolve that problem.

Does it bother you that Saints is only half as long as Boxers?

Michael: Nope. Yang may have used fewer pages for Saints, but I don’t feel like he shorted the story or did injustice to that perspective. If anything, I think it’s cool that he was able to present that point of view so concisely.

Lori: Not at all. Saints didn’t need more pages. It told its story and to go on any further would have belabored the point.

Esther: No. Not at all.

Robin: No problem here. It’s actually rather nice to see that there wasn’t any pressure to make them equal in terms of page count—to me it signals each ended up with the necessary pages to tell their story, and no more.

One of the things I find a bit jarring in both books is the contrast between Yang’s very smooth, fairly simple art and the extreme violence of this story. Because of the lack of detail, there is very little gore in the violent scenes. Do you think this is good or bad? And what about the emotional impact—is it conveyed effectively?

Michael: For me, the simplicity of the linework made the story more unnerving. Had it been super detailed and gory, I would have been more likely to dismiss it as gratuitous and exploitative. Instead, Yang creates tension by depicting these horrible events in such an innocent way. I’m far more disturbed by Yang’s cartoon-like characters committing atrocities than I would be by “realistic” characters doing the same thing.

Lori: I’m glad for the lack of gore in the violent scenes. I think making it gory would have lessened the emotional impact and made the deaths more clinical. The emotional impact is best conveyed through the characters’ reactions to the violence, which is done effectively.

Esther: I found it violent enough without thinking that it could have been more detailed. I think it’s perfectly done.

Robin: Perhaps it comes from reading such a variety of comic styles over the years, but I have begun to disengage style from content. Certainly in the world of Japanese manga there are very stylized characters, cute even, who commit atrocities of all kinds, and cartoonish, simple character design doesn’t necessarily lead me to expect a simple or circumspect story. I think I’m with Michael and Lori in that the lack of detail or explicit gore focuses the upsetting aspects on the emotional side, which makes it harder to gloss over in the reader’s mind.

How do you feel about Bao and Vibiana as characters? In both cases, they take in something without really understanding it and make it their own. Do you think they are heroes? Is one a stronger character than the other?

Michael: That’s a great question. My instinct is to call Bao the stronger character because he starts off fighting for something instead of running away, which is where Vibiana begins. But as she finds her place, she’s just as willing to fight for it as Bao is. I don’t know that they’re especially heroic though. There’s a sense that they’re willing to make sacrifices for the good of others, but the supernatural elements call into question how much they’re in control of their own actions.

Lori: To be honest, I really didn’t like either character, though if there was one I was more sympathetic to, it was Bao. He stumbled a lot, but he actively chose his path, for right or for wrong. I didn’t see either as especially heroic, but they both had their strengths and both wanted to protect what was important to them. I don’t see one character being stronger than the other.

Esther: I didn’t feel overly connected with either Bao or Vibiana, but I was more fascinated by them. These were both very round characters with flaws and many heroic qualities. I could write an argument for either side. But both Bao and Vibiana are equally strong in their own ways.

Robin: I very much appreciated the way both characters take on their missions, as they see them, without completely understanding them. I think that’s one of the hardest things to tackle, that lack of self-awareness, especially what makes society label one person a freedom fighter and one a terrorist. What motivates people to embrace one cause over another is rarely pure, and I think both character portrayals zero in on living with your choices, of learning that motives and action don’t always align. I wasn’t sure when I started these two volumes how much Yang would address what makes someone a true believer or a blind devotee, and I love that in both characters, it’s never one answer or another. All of that being said, I think I most enjoyed Vibiana, precisely because she didn’t have a clear or pure belief from the beginning, and I found her progression believable and ultimately wrenching.

And what do you think of the use of supernatural elements—the gods of the opera in Boxers and Vibiana’s vision of Joan of Arc in Saints?

Michael: I’ve already touched on that. It’s my biggest problem with the two books.

Lori: I thought the use of the supernatural elements reflected well on the each character’s goal. Bao and his co-patriots becoming the gods from the operas showed his nationalistic feelings and pride. It wasn’t just Chinese against foreigners. It was a rich history of China standing with the men and women who fought for their country. Vibiana’s visions were more about her personal journey to accepting Christianity. Though most of the book, she goes along with it because it gave her a home and a name. It isn’t until the end, when she faces both Joan’s and her own death, that seems to actually accept it.

Esther: I felt the gods of the opera worked better into the story than the the Joan of Arc thread. The mysticism and the gods has always been part of the Chinese culture and religion as I know it. So it was natural to the story. But the Joan of Arc storyline was a bigger stretch for me as I never associate Christianity as a religion that deals much with the supernatural. I’m not sure I make much sense.

Robin: As I said above, the supernatural visitations were some of my favorite parts. I think Christianity has a wide range of supernatural ideas it expects believers to accept, and I have always found the story of Joan of Arc to be one of the most remarkable of the saints, given the place and time during which she lived. How much her own visions were real, of course, is a long debate, and just how much was political savvy and clever manipulation of the prejudices and ideals of 13th century France. I liked her appearance as a way to reference a way for a young woman to gain power and a voice against all odds, to be what Vibiana clearly longs for outside her society’s ingrained expectations for women and girls. I also have a fondness for the pageantry and beauty of Chinese opera (thanks to multiple high school viewings of the film Farewell, My Concubine).

I grew up in a household that had almost zero religion in it, but the presence of the supernatural reminds me of my family’s discussions about how while we as a family didn’t subscribe to any organized faith, there’s little difference between believing in quantum physics and in God or gods. Just as much certainty in the face of zero proof is required (despite what they find at CERN). The supernatural elements worked for me because its part of belief—you can’t dismiss the core myths for both sides, and making each character’s faith visible in this way helped show the fluctuations between certainty and doubt.

I found the scene where Bao seals the remaining Christians into the church and sets fire to it to be the most troubling scene in the book. Bao kills the Christians because Ch’in Shih-huang urges him to, but to strengthen himself he listens to what he knows are lies. That suggests that deep down he felt what he was doing was wrong. Yet he doesn’t seem to be at all contrite afterwards—he just moves on without further reflection. What were your thoughts on it?

Michael: That’s where Boxers lost me too. I checked out of any empathy I had for Bao at that point. I suspect that’s what Yang was after, though. One of the things I like about the two books is that neither side is portrayed as entirely good or entirely evil. I do get the sense that Bao is betraying something of himself in that scene and that he’s doing it willingly. He’s all in by that point, which makes him pretty horrible. But though I can no longer relate to him as a character, I can still find him believable, and in the end, that’s more important to this story than my empathizing with him.

Lori: Bao was conflicted. The scenes with him and Ch’in Shih-huang show him disagreeing with him, as Bao keeps trying to hold to the edicts of Red Lantern, and Ch’in want him to follow his path. The scene at the church was his finally giving in, but I didn’t see him as not being contrite, but that he was numb. Hearing the lies let him justify his action, and the action moved the Boxers from an idealistic fight to a declaration of war.

Esther: While Michael said Boxers lost him at the scene at the church, I was very troubled already by the train scene. But yes, this scene was extremely disturbing. It didn’t seem to further the cause of the rebellion.

Robin: I don’t know that I lost empathy for Bao, but it is a troubling turning point. I think the scene in the train shows that he has become what he needs to be in order to complete his task, and that any internal moral conflict has been shoved away. Both incidents show how much a person can compartmentalize actions and willfully shut down doubts. It’s a horrible thing to witness, but I think it’s true to how anyone commits such an act. I appreciate the further lingering question these brutal acts raise: Can anyone come back from that kind of action? Is forgiveness, either by victims or internally, possible?

Was there any other scene that jumped out at you as a key moment of revelation or a turning point?

Michael: There are a couple. Yang did a great job of communicating Bao’s affection for the little god in his village, so I felt it was destroyed by the Christians. That immediately put me on the Boxers’ side for a good, long time and had me rooting for them to kick out their imperialist invaders.

Which meant that Yang had his work cut out for him in making the Christians sympathetic to me again in Saints. He accomplished that by having the harsh, judgmental priest responsible for the god’s destruction be the very person to help Vibiana find forgiveness and peace. I love the humanity of that inconsistency and it instantly endeared me to that character even though I didn’t excuse any of his many wrong-headed actions.

Lori: The burning of the library at Peking was a key moment I think. Bao sacrificed centuries of knowledge and Chinese culture in a vain attempt to get to the foreigners. It was like he was throwing away the very thing he claimed to be protecting.

Esther: Like I said earlier, the scene on the train. That was the point where I felt a strong need to refresh my history. It made me wonder who was “in the right” during this period of history. Of course, there is no right.

Robin: I’m with Lori—the burning of the library is heartbreaking and shows very clearly the muddiness of ideals versus reality.

Both Bao and Vibiana are urged on by a supernatural character to fight for their own vision of China. Yet (spoiler alert!) the Boxer Rebellion was a failure. How do you feel about following Bao on his epic journey only to see it all come to nothing?

Michael: I’m good with it. What’s fascinating about the story to me is the look at the differing points of view that led to the conflict, not so much how the conflict was resolved. That makes it a mature story that won’t connect for every kid but could also be an interesting introduction for children to the idea of ambiguous endings.

Lori: I don’t have a problem with it. I think Bao was following a vision of China that wasn’t going to work in the end. He was being pushed too much by the old ways, which weren’t going to work in the new era of having to deal with other people and cultures. Bao’s vision of a China free of foreign interference wasn’t bad, just the reign of terror he tried to use to get to it.

Esther: It’s a bit unsettling. I wasn’t certain how old he was when starting out, though he seemed very young, and I wasn’t sure how old he was at the end, but it seemed like he was an adult. And I kept wondering, where does he go from here? What’s left? And that’s a bit defeating.

Robin: I am also perfectly happy to follow a journey to defeat. There is always a losing side, after all, and with history being written by the victors, I am always glad to see stories that remind us that the opposition are the heroes on their own side, not just a faceless enemy.

What about Vibiana and her journey?

Michael: I like that it doesn’t really end any better for her. It’s in keeping with the point of the project that there’s no clear winner at the end. Boxers & Saints is extremely anti-war and I’m all for that message in a story for young people.

Lori: I had more trouble with Vibiana’s journey. The point of her following Joan of Arc through her life seem to be to teach her it’s okay to die for your beliefs. But Christianity was a belief she didn’t really feel or understand for most of the story, and she is suddenly converted at the end by Joan’s last revelation. It didn’t really ring true with me.

Robin: I think I went into Saints wondering if it would be, somehow, a more traditional story of strong faith, and I was pleasantly surprised that Vibiana’s story was just as uncertain and full of contradictions as Bao’s. I think that uncertainty is powerful, and I like it when creators sidestep neat answers.

In interviews, Gene Luen Yang says he hopes this book encourages more people to learn about the Boxer Rebellion, because it was such an important turning point for China. It also encompasses many things we are still talking about today—the clash of cultures, imperialism, the place of religion. What sort of parallels can you draw with our modern world?

Michael: As divided as our world is right now, I feel like humanity is in a new place where we’re more equipped than ever to see other people’s points of view. I’m optimistic about our ability to continue moving in that direction and see literature like Boxers & Saints as an important part of that journey. Anything that encourages readers to view the world from someone else’s perspective is a wonderful thing and we especially need that now.

Lori: I really regret not taking History of China when I was working on my minor in college. There is so much that could help explain east-west relations. Seeing how the Chinese were treated by Europeans in their own country makes it hard to blame them for their continued mistrust of the west. The closest parallel I can think of would be with the Middle East. Both culture clash and religion are playing important roles in our relations with them, with both sides not willing to listen to the other, innocent bystanders being fair game, and dying for one’s cause or religion being not only accepted, but encouraged.

Robin: I definitely hope readers will go and research more about the Boxer Rebellion, and anything that embraces the complexity of conflict is A+ in my book. I work in a community where we serve a large Chinese population, and I fear there is a general lack of knowledge about Asian history and how people are still affected by it today.

I think Boxers & Saints fits well in with the trend in recent stories aimed at teens—I’m thinking here of prose works like Kristin Cashore’s Graceling, Fire, and especially Bitterblue, Patrick Ness’s Chaos Walking series, Melina Marchetta’s Finnikin series, and even Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games—all about young people caught up in conflicts and of the difficulty in reconstruction and reconciliation. We don’t witness reconciliation in Boxers & Saints, but we are shown the history as it happened on a personal scale, and then left to seek out what happened next.

The majority of today’s conflicts, from Syria to Egypt to Sudan to our own extreme camps fighting it out politically in the US, mix religion, ethnicity, culture, and belief explosively. With the move away from the more clearly defined conflicts of nation state against nation state, every conflict is hard to simplify into good guys and bad guys. I think any story that helps young readers understand how complex any conflict is will help them approach all battles, large and small, with open eyes.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Roundtables, Young Adult

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

I had no problems with Viviana’s conversion to Christianity. I’m half-Japanese, and one of my ancestors was a Catholic martyr (Lady Gracia), and some of my Japanese uncle’s ancestors were among the early Christian converts as well. What Vibiana went through is not all that different from what my ancestors and my relative’s ancestors went through. Because of my family background, reading Boxers & Saints was heartwrenching and immediate. Yang’s choices seem absolutely logical to me.

Sheesh, it would help if I were consistent in spelling Vibiana’s name.