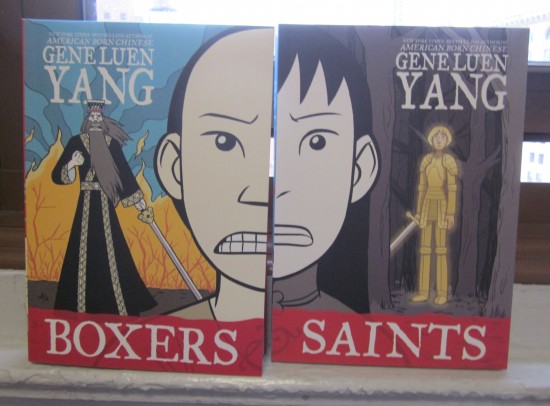

Interview: Gene Luen Yang on Boxers & Saints

As the 19th century turned into the 20th century, China was wracked by what has become known as The Boxer Rebellion. It was a violent uprising in which poor, rural, nationalist Chinese fought back against the pernicious influence of imperial Western powers on their own country and their culture, using whatever weapons they had available to them.

It is also the subject of an ambitious new two-volume historical graphic novel by cartoonist Gene Luen Yang, whose best-known work, American Born Chinese, detailed the assimilation anxieties of Asians in a not-always-friendly American culture.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Each volume of Yang’s Boxers & Saints stars a different young protagonist on a different side of the traditional Chinese vs. Western Christian conflict at the center of the Rebellion.

In Boxers, we follow Little Bao, a young boy who admires older men like his father and local hero Red Lantern Chu for standing up to the Western Devils. After he himself learns a secret, mystical form of kung fu, he becomes a leader of an increasingly brutal military movement, marching on the capital under the counsel of the spirit of Ch’in Shih-huang, China’s first emperor.

In Saints, we meet Four-Girl, a mischievous, put-upon young girl who stumbles into Christianity through less than noble purposes—seeking to become a “devil,” for example, or simply to get access to the cookies her patron provides while preaching about Christ. She seems to be on the right track though, as she soon sees visions of a mysterious young Western woman who she eventually learns is Joan of Arc, and the church gives her something even her own superstitious family never did, a name, after which point she becomes Vibiana and finds herself counted among the Boxers‘ enemies. A sweeping, epic narrative that infuses its historical events with mystical elements and some difficult questions of faith and identity, it was a very personal story for Yang, who is himself both Chinese and Christian. At turns horrifying and humorous, it’s the writer and cartoonist’s biggest and most powerful work to date.

GC4K: It occurred to me while reading Saints, when we see Four-Girl’s questions of the mysteries of Christianity, that you seem to know the faith from the inside out, and I seem to recall that you’ve taught at religious schools in past biographies of you I’ve read.

As a tension between the stories of China and her gods and the West’s Christianity are at the core of the story, how personal a story was this for you?

Obviously we’re quite far removed in time from the events of these stories, but have you felt that tension in your own life, or did you find yourself projecting yourself into the story when it comes to these issues?

Gene Luen Yang: I’m a practicing Christian—a Roman Catholic to be specific. I grew up in a Chinese American Catholic community in the Bay Area. After going through a period of doubt in college, I decided to remain Catholic as an adult. I currently work part-time at Bishop O’Dowd High School, a Catholic high school in Oakland, California. I’ve taught computer science, math and art there in the past, but I’m outside the classroom now, doing database work for them.

The central tension in Boxers & Saints is very personal. When I was little, because I grew up in that Chinese American Catholic church, Christianity and Chinese culture seemed to go hand-in-hand. Whenever folks around me were talking about Jesus, they were doing it in Chinese. And historically, Christian churches in Chinese American communities have served as hubs for cultural preservation. Often, the parts of Christianity that get emphasized are those that overlap with a Confucian worldview.

As I got older, I began to realize this wasn’t always the case. In China just over a hundred years ago, being a Chinese Christian was seen a a contradiction. Embracing a Western faith meant turning your back on Eastern culture. An acquaintance of mine once asked me, “Why would someone of Eastern descent become Christian? The Eastern faiths have so much wisdom and beauty.”

It was a good question. Boxer & Saints is me wrestling with that.

GC4K: On a related note, and perhaps a better first question than a second question, what drew you to this particular story as your next project? It’s certainly a big, ambitious and, I would imagine, challenging one, from the point-of-view of the creator.

Yang: Boxers & Saints is definitely my most challenging project to date. I first became interested in the Boxer Rebellion in 2000, when Pope John Paul II canonized 120 Chinese Catholic saints. My home church was incredibly excited about this. We had all sorts of celebrations and special masses. When I looked into the lives of these saints, I discovered that many of them had been martyred during the Boxer Rebellion. The more I read about the Boxer Rebellion, the more conflicted I felt. Did I sympathize more with the Boxers or their Chinese Christian victims? That’s why the project ended up as two volumes. The protagonists in one are the antagonists in the other.

GC4K: At this point in your career, you’ve had the opportunity to both write and draw your own comics as well as serve as a writer on stories that other artists would draw. Why was this a comic you decided to draw yourself, instead of working with a collaborator?

Yang: When you write and draw a comic, you have complete control over it. Every line and letter comes from you. When you work with someone else, you lose control, but hopefully you gain something in return. A collaborative comic is an expression of the relationship between the writer and the artist rather than an expression of a single person’s vision.

For this particular project, I felt like I really needed that control to get across what I wanted. That said, it’s still a collaboration of sorts. I asked Lark Pien to color the book. She’s the creator of Long Tail Kitty and Mr. Elephanter, two amazing kids’ books. She’s also the colorist of American Born Chinese.

GC4K: The format of this story is unusual in that it occurs in two separate but connected books, in which the narratives intersect at several points, and we see the same events told from different points of view in several places, as you’ve mentioned. Can you tell us a little bit about why you decided upon this particular way of telling the story?

Yang: I wanted to show that the same event could be interpreted in radically different ways, depending on a person’s life history. For instance, some of the Christian missionaries back then would go into Chinese villages and smash their statues of Chinese gods. When I first read about that, I had a visceral reaction to it. What a horrible and disrespectful thing to do.

But at the same time, there was a segment of the Chinese population who had a hard time fitting into mainstream Chinese society, who felt oppressed by traditional Chinese beliefs. To those people, the smashing of the gods—these embodiments of Chinese culture—could be seen as freeing and hopeful.

GC4K: Did you work on the books simultaneously, or did one get written before the other? Why is Boxers so much longer than Saints, beyond the obvious reason that the protagonist of one outlives that of the other?

Yang: I outlined both books. Then I wrote Boxers. I wrote Saints as I was drawing Boxers. I took a break to work on a superhero project (The Shadow Hero, illustrated by Sonny Liew and due out from First Second Books in 2014) before drawing Saints.

Pretty early on, I realized that the two books didn’t match up perfectly. Historically, the Boxers went on this epic journey. They marched from village to village, all the way to the capital city, fighting along the way. I wanted their story to be a comics version of a Chinese war movie, colorful and bloody and tragic.

The Chinese Christians just didn’t have the same kind of story. They stayed in their villages, fought off the Boxers as best they could, and eventually died for their beliefs. Their journey was an internal one. They struggled with doubt, with questions of identity and fate and divine will. I knew their story had to be quieter, shorter, more humble, so I took inspiration from American autobio comics. That’s why Saints is shorter. That’s why I didn’t use rulers to draw the panel borders, the way I did for Boxers. That’s why Lark gave it a more limited color palette.

GC4K: Can the books be read independently of one another, do you think? Obviously together they give two different sides—or, really, points-of-view—of a single conflict, but are they complete in and unto themselves? Personally, I was a little surprised that reading Saints changed the ending of Boxers, and where and when its protagonist Bao’s life seems to end, for example.

Yang: I hope they can be read independently. I did them as two separate volumes to force myself to give each a satisfying beginning, middle, and end. I also hope that folks who read both will get something out of the dialog between the two books.

GC4K: I confess a great deal of ignorance about the Boxer Rebellion, which is a term I have heard and a conflict I had only the most basic ideas about (Everything I knew about it came from researching for a fifth-grade report on the history of China, and oh how I wish there was a comic book full of kung fu fighting and mystical figures I could have read back then!)

So forgive me if this is a completely ridiculous question, but are Bao and Four-Girl real people? Are any of the ancillary characters, like Father Bey or Red Lantern Chu?

Yang: Before I started the project, I didn’t know much about the Boxer Rebellion either. And I’m certainly no expert now. Bao and Four-Girl aren’t real people.

Nobody really knows how the Boxer Rebellion started. It started with the poor, and poor people’s history is rarely written down. I read a bunch of books, but the best one by far was Joseph Esherick’s Origins of the Boxer Uprising. He gives the best guess I read as to what exactly happened at the beginning of the movement. I tried to weave pieces of what he wrote into Bao’s story.

Four-Girl is inspired by a relative of mine. My relative was born on a bad luck day, according to traditional Chinese beliefs. Because of this, her grandfather hated her. He would dote on her siblings, but not her. She converted to Catholicism as an adult, and although she herself never connected her conversion to her childhood experiences, to me the connection was clear as day.

Some of the characters are based on historical figures. A traveling cooking oil salesman named Red Lantern Chu was prominent in the beginning of the movement. Master Big Belly is based on an itinerant martial arts master who Esherick describes in his books. Rumor had it that he had a mystical eye in the middle of his belly.

Father Bey is a stand-in for the Franciscan missionaries in China, though historically they were mostly Italians sponsored by the French government, not French. Prince Tuan, the Kansu Braves, and Baron von Ketteler were all historical figures.

Dr. Won is based on a Chinese saint named St. Mark Ji Tianxiang. Like Dr. Won, St. Mark was an acupuncturist and a devout Catholic for all his life. He struggled with opium addiction. His parish priest refused to give him the sacraments for the last 30 years of his life, and he died an addict during the Boxer Rebellion. He was one of the 120 canonized by Pope John Paul II.

GC4K: Can you tell us a bit about the design process of Four-Girl? She has a very specific look with a very unusual face, even before she goes through her “devil-face” phase. She’s one of those rare comics characters that it always makes me smile just to look at, whether or not she’s doing something funny in a particular panel or scene or not.

Yang: Ha ha. I ‘m glad you thought so! I wanted Four-Girl to have an expressive face, a face that could hold her devil face. I also wanted her to look really different from Mei-Wen, the primary female character in Boxers. I gave Four-Girl unbraided, unbound hair because I’d read somewhere that in turn-of-the-century China, having braided, bound hair meant your family cared about you. I don’t remember the source so I’m not sure how true it is, but I thought it’d be a cool little visual detail to include.

GC4K: I wanted to ask you a little bit about your art style in this particular work. You’ve demonstrated a fairly versatile style in the past, so I was curious how you arrived at drawing this story in this style. I noticed the cartooniness—the relatively few lines, the simple shapes of the figures, etc—worked to diffuse some of the gore and violence a bit. There are plenty of upsetting scenes in the book, but the way you draw throats being slip and people being shot in the head made the violence a lot less…visceral or tactile, I guess.

Yang: You really think my style is versatile? I’ve always felt that it’s pretty limited. I kind of draw everything just one way. I’m trying to break out of that, but it’s hard.

I did try to “cartoonify” the violence to make it more palatable. As part of my research, I visited this Jesuit archive in France where they kept the photos and letters of French missionaries in China. They had photos of these incredibly inhumane acts of violence, of beheadings and torture. It was overwhelming. I didn’t want to overwhelm my reader.

That said, there are a couple of scenes in each book where I did want the horror to come through. When I show Red Lantern Chu’s fate, for example. I wanted the reader to feel what Little Bao feels.

GC4K: Among the tragedies of the story is that Little Bao and Four-Girl encounter one another in passing very early in life, before either of them set out on the paths that lead them into the conflicts that they played such integral roles in. Would their stories have been different inf they had met and befriended one another at that point? They both essentially want the same things, and it seems like circumstance as much as anything else that keeps them on their sides of the conflict.

Yang: That’s something I was hoping to hint at. Maybe if they’d both been born a hundred years earlier, or if they’d grown up in the same village instead of neighboring villages, things would’ve been different between Little Bao and Four-Girl. They both want wholeness, a completeness of identity, but they go about getting what they want in very different ways.

GC4K: One of the many challenging aspects of Boxers is watching Bao grow from such a traditional, sympathetic, “good guy” protagonist into crossing the various lines he does, until he’s committing pretty monstrous acts. That is diffused somewhat by his conversations with Ch’in Shih-huang, who the reader can “blame” for some of the most heinous things Bao does in the book.

Is that the role you intended for the emperor, or was there more to your inclusion of what would seem like the most fantastical, or at least mystical, elements to both stories?

Yang: Ch’in Shih-huang (or as we’d translated his name today, Qin Shi Huang) is a historical figure. He’s the first emperor of China, the guy who put China together. Through lots of brutality and blood, he united seven kingdoms into a single nation. He built the Great Wall. He was buried with the Terracotta Soldiers.

Most Chinese feel ambivalent about him, I think. They’re proud of the nation he created, but he was a maniacal tyrant. Her buried people alive and burned books. His dynasty didn’t last all that long, only a few years after his death, but his spirit has haunted China ever since. For instance, Mao Zedong saw himself as a modern Qin Shi Huang, and bragged about how he buried more scholars and burned more books than the first emperor. The Boxer Rebellion was a response to the possible breaking up of China, so I thought it appropriate to have Qin Shi Huang’s spirit haunting Bao.

GC4K: Joan’s interactions with Four-Girl/Vibiana are even more ambiguous. They seem more objectively real (That is, Four-Girl has no idea who Joan of Arc is but sees her anyway, whereas Bao is familiar with most of the gods of the opera he deals with), and Joan’s struggle to unite her country seems to be the goal of the Boxers, rather than the Christians Vibiana is with. Faith aside, Joan shares more in common with Red Lantern Chu than Father Bey and the Westerners, doesn’t she?

Yang: I included Joan of Arc because she’s essentially a French Boxer. The Boxers were poor teenagers living in the farmlands of China. They were angered by the foreign incursion into their homelands. Empowered by strange mystical beliefs, they fought back.

Joan was a poor teenager living in the farmlands of France. She was angered by the foreign incursion into her homeland. Empowered by strange mystical beliefs, she fought back. Her story points to the common humanity between the Boxers and the Europeans. Within the stories of the Boxers’ enemies was a figure very much like themselves.

GC4K: Through Joan and Jesus’ intervention, Vibiana does manage to save the life of the man who kills her, which seems a rather admirable martyr-ly/saintly Christian death to experience.

Yang: Yes. But she doesn’t know it at the time of her death. I’m attracted to the spiritual thinking of Therese of Lisieux, Henri Nouwen, and Thomas Merton. Even if you can’t figure out the big questions, the little things—the everyday kindnesses—still count. Vibiana struggles with this idea of calling. Should she defend the Catholics of her village? Or should she become like Joan and defend her nation? How does she fit in the tides of history? She never gets a satisfying answer, but her small kindness to her own murderer still has an impact. It still counts.

GC4K: Was the cover design a deliberate echo of that of American Born Chinese?

Yang: Colleen AF Venable, the graphic designer at First Second, worked with me on those covers. It took us a while to arrive at them, but we’re pretty pleased with how they turned out. The goal was to create something both familiar and new. We wanted them to be familiar to readers of American Born Chinese, but also feel like an entirely new project.

Gc4K: One of the more disturbing elements of the book was the way in which both Bao and Vibiana, despite supernatural guidance, seem to have been wrong. Neither accomplishes their goals and both cause suffering to those around them, particularly poor Bao, who leads so many others to their deaths and takes so many lives himself.

And yet one of the more hopeful elements also has to do with the supernatural involvement, in the way Guan Yin appears in Boxers and Jesus in Saints, in parallel images suggesting a similarity of the two figures and their attendant faiths.

This is a tough book to digest, and leaves a lot for readers to wrestle with. Is there a “right” answer in all this? A lesson to be taken away to help readers cope with making sense of war and conflict in their own lives? Or is that wrestling what you’re trying to encourage more than a particular, Aesop’s fable-like moral?

Yang: Years ago, I saw this painting of Guan Yin in a museum where she was surrounded by a halo of hands with eyes in them. I was struck by how much those hands with eyes looked like hands with holes. Guan Yin is a Christ figure. Or if you’re a devotee of Guan Yin, you could say that Christ is a Guan Yin figure. Both their stories exemplify self-donating love. They show the importance of self-donating love within all human culture.

I felt really sad about everything as I was working on Boxers & Saints. The Boxer Rebellion itself seems murky to me. Even after being immersed in it for six years, I still can’t say who the good guys and the bad guys are. But again, I would go back to what we’d talked about earlier. Even if you don’t get definitive answers to the big questions, the little stuff counts.

GC4K: What do you think your version of Ch’in Shih-huang would think of China today? What would Joan of Arc think? And Bao and Vibiana?

Yang: I’m definitely no expert on China. I’ve only been there twice. My experience of Chinese culture has largely been through echoes, through my family and my community here in America.

China’s been through a lot over the last two centuries. The Chinese have experienced some of the most heinous decades in history. Today, some of the very things the Boxers fought against have taken hold in China. The Chinese wear Western-style t-shirts and jeans. They listen to Western-style pop music and watch American blockbuster movies. They run American-style businesses.

Also, Christianity is growing rapidly in China. By some estimates, there will soon be more Chinese Christians than members of the Chinese Communist Party. Joan would probably be happy about that.

My version of Ch’in Shih-huang might see all this as a defeat, but I think he’d be wrong. Chinese culture has incorporated Western elements, but it’s using those Western elements to express a distinctly Chinese worldview. Take comics, for example. Chinese comics use word balloons, sound effects, cinematic compositions—conventions rooted in the West—to tell stories of the Monkey King, Guan Yu, and other traditional Chinese heroes and gods. Maybe both Bao and Vibiana would feel at home in this combination of the familiar and the new.

Filed under: Interviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT