Interview: Editor Chris Duffy on Fairy Tale Comics

While several aspects of comic book creation rarely get the attention they deserve (think lettering and coloring, for example), none gets shorter shrift than comics editing, perhaps the most invisible part of a finished comic book. Due to the nature of the work, which naturally occurs behind the scenes, no one ever really gets to see, let alone appreciate, what a comics editor contributes exactly, aside from the editors themselves and the artists they work with.

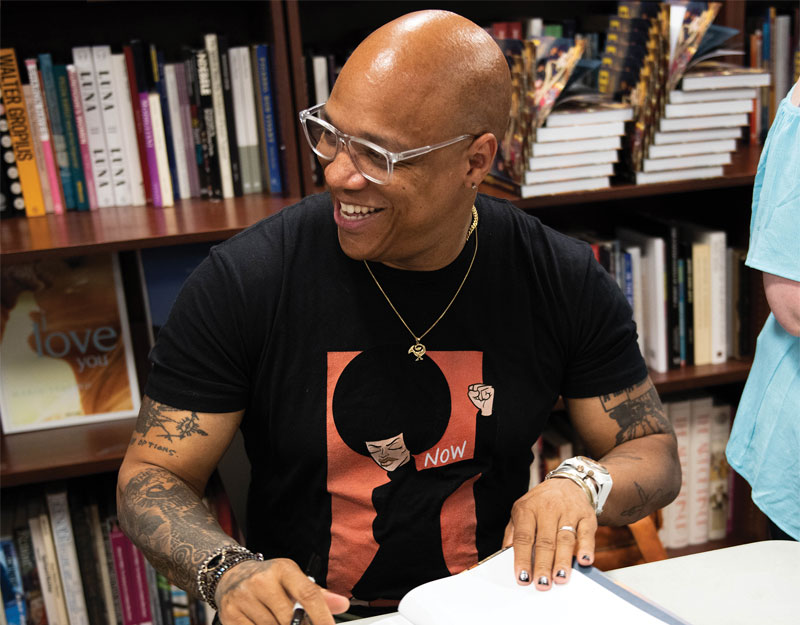

It speaks to Chris Duffy’s abilities and influence then that he is one of a handful of “name” editors, and one many comics readers of a certain type might point to as being one of their favorite editors. Duffy edited the comics section of Nickelodeon Magazine for 13 years, an endeavor that matched the work of cartoonists like Craig Thompson, Sam Henderson, Richard Sala and Steve Weissman with an appreciative audience of children, and he currently edits United Plankton Pictures’ monthly SpongeBob Comics, an anthology gag comic that mixes rather faithful to the show SpongeBob strips with more idiosyncratic, auteur takes on the characters.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In 2011, First Second released the Duffy-edited Nursery Rhyme Comics, an anthology in which 50 cartoonists adapted 50 nursery rhymes into short comics. Now, the publisher and editor have reunited for a follow-up book of sorts, Fairy Tale Comics.

Once again Duffy has assembled a murderer’s row of great cartoonists, including Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, Raina Telgemeier, Graham Annable and David Mazzucchelli, among a dozen others, to retell fairy tales familiar and less-familiar in their own personal, often inimitable styles.

We recently spoke to Duffy about— Wait. Let’s try to fairy-tale it up a bit.

Once upon a time (there, that’s better), we spoke to the young prince about his quest to create a charming collection of comics based on beloved fairy tales to entertain all the readers, young and old alike, in the kingdom of comics (Eh, maybe we over fairy-taled it there).

GC4K: In your editor’s note at the back of the book, you mentioned that preparing for the book involved reading a lot of fairy tales. I was hoping you could walk us through the narrowing-down process and the matching creator-to-tale process.

How did you finalize which tales to include and who would be drawing which of those ultimately chosen…?

Chris Duffy: Okay, but remember—you asked for it! I kept a couple of notebooks where I listed every fairy tale I read. This was mostly to just reinforce any thoughts I had while reading and so I’d have a list somewhere other than the table of contents of the book. Once well into the reading I started a lineup of stories for the book. Then I would take a look at it occasionally and try to balance things out, get rid of overlapping themes, or make room for a type of story that I felt needed to be represented. This list kept evolving right up to the point where we had the book filled.

Matching cartoonists to creator was another list-oriented task. Calista Brill (my First Second boss) and I would agree on a list of “best” creators and when it started getting to be time to get things moving, I began to contact creators on the list. Matching them to a tale was fairly unscientific, but ultimately worked out.

Vanessa Davis’s comics crack me up and she draws good fluffy animals. “Puss in Boots.” “Snow White” is a hugely iconic fairy tale. Who is my favorite cartoonist—to show the world how it’s done: Jaime Hernandez! I’m a big enough fan that linking a story to a cartoonist is easy; I do it in my head all the time!

GC4K: Was the pool of talent you pursued pretty large as well, or are the artists in the book the only artists you approached? Were you unable to get anyone you really wanted?

Duffy: It wasn’t a much larger pool than we ended up using. A few people were too busy or thought they weren’t appropriate for the book. It was disappointing, but I have a short memory for the no’s, since everyone who did eventually say yes did such amazing work.

GC4K: Similarly, were there stories you really wanted to include, but didn’t have space for, or didn’t have anyone as interested in drawing them as some of the others?

Duffy: There’s a type of story starring a group of men (often war veterans) who each have a special power: strong, super fat, super hearing, incredible marksmanship, etc. “The Six Servants” is the most famous, maybe.

It’s a totally a natural fit for a fairy tale comic book but there wasn’t room. There were plenty more, too many to list, that I loved that for one reason or another didn’t end up in the book. (Okay, I’ll list two: “The Queen Bee” and “The Fisherman and His Wife.”)

Also, we didn’t do “Cinderella!” I can’t believe we didn’t do “Cinderella.” Feels almost rebellious.

GC4K: You had also noted that some pains were taken to include “non-European traditions” and a mix of boy and girl heroes, and while that is evident, I see there was also a variety of tones to the tellings. That is, some are drawn and played pretty straight, with images that wouldn’t have been out of place in a Andrew Lang or Grimm collection, while other feature much more cartoony, modern or silly art, and are played more humorously.

Did the tone of each piece come down to the choice of the artist, or was tone and art style other things you guys were looking for and encouraging a variety of as well?

Duffy: The artists really chose the tone for their specific story; but as you imply, yes, I sort of indirectly directed the tone of a story by choosing a specific artist. That said, I was usually happily surprised that most comics ended up different than I’d imagined. David Mazzucchelli could have gone for a much darker approach to “Give Me the Shudders” (his version of “The Boy Who Set Out to Learn About Fear.”) But his humorous, clear line approach is a real delight, and is weirdly scary in its own way in places.

GC4K: The “Rabbit Will Not Help” story and “The Boy Who Drew Cats” story (which was one of my favorites) represent the “non-European” stories you were looking for; was it particularly difficult to pick a few stories from a potential pool like that which had to have been both huge and full of less-familiar stories? (At least compared to, say, “Little Red Riding Hood” or “Goldilocks and The Three Bears,” and many of the others which likely come to mind as soon as someone hears the word “Fairy tale”).

Duffy: I think the “non-European” angle can be overstated. (Though you’re right that I used it to mean “not super famous or Grimm.”) In fact, I did not attempt to familiarize myself with every fairy tale tradition, because that would have taken for-freaking-ever! I read a very light smattering of Japanese, Chinese, American Indian, African-American, and “1001 Nights” stories. I didn’t even read a whole book of any of those!

And I would even argue that there’s hardly such a thing as “non-European” fairy tales anymore; the reprinting of “foreign” fairy tale traditions has been a lucrative business for publishers for more than a 100 years now. They are in some ways very much a part of the Western canon. I don’t mean to split hairs, but I think it’s interesting.

In the case of “The Boy Who Drew Cats,” for example, I came across it in an Andrew Lang-style fairy tale collection (I don’t recall which one) and then tracked down the writing of the author, Lafcadio Hearn (an Irish-Greek-American writer), via Project Gutenberg. The story is originally Japanese, but my experience of it is totally through European sources. And yeah, it’s a great story and the amazing Luke Pearson told it beautifully and hilariously. It feels almost like a new definitive version of the story.

GC4K: I was interested that you mentioned a mixture of boy and girl heroes, because it seems that the fairy tale is one type of story that has always been fairly balanced between boy and girl protagonists. Certainly the princesses often need saving, but often times they save themselves by being kind and thus earning supernatural, non-male help (from fairies or animals and so on).

Many of the stories do seem to feature tweaks in the sexes of the heroes though—for example, the Woods-“man” who saves Little Red Riding Hood is a woman, the puss in “Puss in Boots” is a female—or the women characters playing more active roles in their own stories, as in “Snow White” and “Rapunzel.”Was this something individual creators seized upon, was everyone pretty much on the same page about making more 21st century versions of the stories, or was it a sort of directive?

Duffy: The main directive was to not do a revisionist or “Fractured Fairy Tale” (or MAD) version of the source story. By revisionist, I mean turning the story on its head by, for example, flipping the point of view (“Hansel and Gretel” told by the witch). But slight alterations to the cast or story were up to the creators.

There were some interesting changes that might have slipped by a few people: In “The 12 Dancing Princesses” for example, the Emily Carroll changed the age of the hero, had him earn his cloak of invisibility through an act of kindness, and made pains to create an initial attraction between the youngest princess and the hero. She did it so well, it feels completely right. These kinds of changes were very welcome (as we wanted part of the fun to be seeing your favorite cartoonist adapt a story).

GC4K: A similar instance of the aspects of original tales that seem very dated was Joseph Lambert’s “Rabbit Will Not Help,” which I didn’t even recognize as a Br’er Rabbit story until the gets stuck to the tar dummy. Those tales have a pretty troubled history in terms of the way they portray race and region, but here the story is so distilled there’s no evidence of that. Were there other examples of stories that needed to be universalized or updated?

Duffy: Joseph Lambert’s great “Rabbit Will Not Help” was actually adapted from a non-“Uncle Remus” version of the tar baby story that did not have such heavy dialect and had a slightly different take on the story. So it started out a little further away from the familiar story. Yes, the Rabbit (et al) stories can be problematic, but I don’t think anyone wants them to be forgotten or go away. It felt right to find a place for it, and choosing a different source for it worked out for the book and the reader, I think. Plus Joseph’s adaptation is really special and turns the trickster into a kind of high-school loner.

I don’t know that we asked anyone to universalize or update anything, but I certainly was careful to not choose any story that felt rooted in something hateful (or too horrific) since the collection is for all ages. I steered wide of “The Robber Bridegroom” for example, because it is just too brutal and scary. Though quite a great story!

GC4K: Were you very involved with each story as it came about, in terms of their stages of development? If so, I was wondering if any of them started out as too familiar or too Disney and the creators needed pushed—or if any of them expressed concerns themselves while working on them—with finding their own versions of the stories and characters.

In many cases, these stories have been illustrated hundreds if not thousands of times, and in a few instances there’s likely a very strong, very pervasive pop culture version. For example, obviously Disney didn’t invent Snow White or anything, but the animated version certainly seems to exert an incredible gravity in terms of popular perception of the character.

Duffy: The cartoonists turned in a sort of working story in sketch form to start. Nobody ever had to be pushed to make their story more personal of less familiar. I don’t know many cartoonists, especially among the gang we rounded up, who need to be pushed to be more idiosyncratic!

GC4K: We could go through the whole list of contributors and I could ask you why each particular one was chosen, but I’ll spare you and the readers that.

I did want to ask you about Ramona Fradon in particular though, because you recently had her contribute to SpongeBob Comics, and here she collaborates with you yourself on a story. That seems to suggest a particular appreciation or affection for her work on your part, and she seems somewhat unique in the stable of creators included for her early career in superhero comics (In fact, I may be mistaken, but I think only she David Mazzucchelli and Karl Kerschl are among the contributors best known for superhero comics).

So, why Ramona Fradon? And what particular quality of her work draws you toward working with her?

Duffy: It was really down to having worked with her off since about 2001, on SpongeBob Comics and other features for Nickelodeon Magazine. So I knew that not only does she draw beautifully, she’s great to work with and fun to talk to on the phone!

I do think her style is very distinct, so to me she is a great fit for the book. She brings a lot of feeling and thought (and humor!) to everything she works on; and she’s not afraid to tell writers (like me) when their story isn’t up to snuff. (I did at least two major revisions on the “The Prince and the Tortoise” script based on her feedback.) And, yeah, it’s exciting to work with a legendary comic book artist. But why don’t more anthologies reach out to older generations? I honestly don’t get that.

GC4K: This book follows the similar Nursery Rhyme Comics anthology. Was it easier or harder to edit, in general?

I seem to recall there being many more obscure nursery rhymes—perhaps because we don’t carry as many of them with us throughout our cultural lives as we do the stories of “Snow White” and “Little Red Riding Hood”—and those seemed naturally suited to shorter adaptations. That is, a few lines of verse seems easier to turn into a few pages of comics than a few thousand words of prose might, in the case of longer stories like “The Twelve Dancing Princesses” and “Baba Yaga.”

Duffy: Nursery Rhyme Comics has 50 contributors and Fairy Tale Comics has 18. So Fairy Tale Comics was easier in terms of numbers of emails and phone calls. So there’s that. Researching fairy tales took longer; there are more to read. Virtually every English nursery rhyme can be found in just a few sources.

As for the adaptations—it is an interesting contrast, like you say. The shortness of the nursery rhymes, plus their essence as something spoken or sung, meant that most of the comics in that book were very interpretive; fleshing out ideas, creating backstories, etc. There was a delight in just seeing crazy stuff happening that you never would associate with a rhyme, as in Tau Nyeu’s Rock-a-bye Baby, which features a wolf, sheep, and a chainsaw.

Fairy Tale Comics is more about adapting and less about interpreting. Easier or harder? I don’t know!

GC4K: Was it always the plan to do a Nursery Rhymes and Fairy Tales volume? And, if so, why did you start with Nursery Rhymes before moving to Fairy Tales…?

Duffy: The Nursery Rhyme Comics idea came first, from Laura Wohl, associate publisher at Roaring Brook. Since things went well, First Second thought Fairy Tales was a good follow up!

GC4K: Do you intend to do second volumes of either? There certainly seems to be enough material.

Duffy: Only time will tell, but it would be fun. In the mean time we are working on Fable Comics.

GC4K: I’ll leave you with a hard, or at least vague, one. In terms of a pop culture trends, fairy tales have been “hot” over the course of the last few years, on television, in action/horror/romance tinged teen-focused movies and in YA fiction.

As someone who spent a lot of time recently reading a lot of fairy tales, do you have any thoughts on what about them might be speaking to our pop culture at this particular point in time? Is there something about the classic fairy tale characters and their stories that speaks to our current zeitgeist?

Duffy: I’m really sorry to answer this way, but I have no idea at all! But I’d recommend that anyone interested in those questions to read a lot of fairy tales, as well as the works of scholars Jack Zipes, Mary Tatar, and Ruth B. Bottigheimer.

Filed under: Interviews

About J. Caleb Mozzocco

J. Caleb Mozzocco is a way-too-busy freelance writer who has written about comics for online and print venues for a rather long time now. He currently contributes to Comic Book Resources' Robot 6 blog and ComicsAlliance, and maintains his own daily-ish blog at EveryDayIsLikeWednesday.blogspot.com. He lives in northeast Ohio, where he works as a circulation clerk at a public library by day.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

I love these classic stories. I like what Duffy did with the nursery rhymes so I expect to like the longer fairy tales too. They are told and re-told for a reason. Several themes and images have stuck with me from a childhood readings Lang’s yellow fairy tales. Seeing vivid, well drawn current takes will be a treat.