Roundtable: Should Parents Limit Comics Reading?

Limit comics reading to only one day a week? Are reading comics and prose equal? Do children have to read both comics and prose? Are comics “real” reading?

Last week, in an article titled “Why My Daughter Isn’t Allowed to Read Comics,” Jonathan Liu at GeekDad posted that he and his wife have limited their daughter’s comics reading to one day a week to ensure she would pick up some prose novels.

While no one here at Good Comics for Kids wants to point fingers at anyone’s parenting decisions, his post brings up some interesting ideas. As a mix of parents, librarians, and educators, we thought we’d join the discussion.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Should Parents and Teachers limit the amount of comics children read to ensure they’re reading prose?

Mike: I don’t know if there’s been a recent study comparing if reading strictly only comics (comic books/strips) will lead to poorer reading habits. Certainly it couldn’t hurt to make sure your child is reading a mix of prose/comics/hybrids. I’m of the longtime mindset that any reading is good reading.

Lori: I don’t see how limiting one will ensure the other, unless the child is forced, and trying to force a child into doing anything is always a lost cause. In my experience, prose or comics, if a child doesn’t want to read a certain format, they are going to resist until the bitter end, and limiting one isn’t going to ensure a rise in the other.

Esther: I would love to see a study like the one that you described, Mike. My librarian instinct says reading is reading, but the part of me that works in a school setting understands the pressures that the Common Core initiative is setting. And Liu says it in his post, that reading comics exercises a different part of the brain than prose (or nonfiction) does. (He doesn’t mention nonfiction. I wonder what his thoughts are on that!). I do believe it’s important for children to be exposed to all sorts of reading. Childhood is the greatest time of exploration. So I do think children should try their hand at all sorts of reading, but I believe there are other methods to get children to reading prose than by limiting comics to one day a week.

Esther: I would love to see a study like the one that you described, Mike. My librarian instinct says reading is reading, but the part of me that works in a school setting understands the pressures that the Common Core initiative is setting. And Liu says it in his post, that reading comics exercises a different part of the brain than prose (or nonfiction) does. (He doesn’t mention nonfiction. I wonder what his thoughts are on that!). I do believe it’s important for children to be exposed to all sorts of reading. Childhood is the greatest time of exploration. So I do think children should try their hand at all sorts of reading, but I believe there are other methods to get children to reading prose than by limiting comics to one day a week.

Michael: I related to Liu’s dilemma a little. My son loves books of all kinds and loves to read, but when it comes to his homework, he can be lazy. Last year he was required by his teacher to read for 50 minutes a day, which I thought was great. I imagined all the novels and series he’d be able to get through with a schedule like that. The reality, though, was that he would re-read the same stuff over and over and always beneath his level. Sometimes that meant comics, but not always. As the year progressed, however, we noticed that he wasn’t improving in areas like spelling, vocabulary-building, and reading comprehension. The lesson we learned was that not all reading is equal.

So, while I don’t at all think that comics are a lesser form of literature than prose, I applaud Liu for trying to find ways to nudge his daughter out of her comfort zone. Restricting her comics reading may be exactly what she needs, but that specific restriction wouldn’t benefit every child.

Esther: Michael, you’ve hooked me on “nudging kids out of their comfort zone.” I think that’s really important for kids. And you’re definitely right Liu’s method wouldn’t work for all children.

Robin: I definitely agree with Michael and with Liu himself that nudging kids outside their comfort zone can be a good and necessary prompt. Reading comics and prose IS a different skill. I believe they’re both equally valid skills, in terms of parsing storytelling, so I can see why a parent would want to balance between various formats.

However, I did notice a few notes in the article that made me wonder more  about the prose options his daughter was given. A few quotes: “My wife mentioned a list of books that she had read by the time she was entering fifth grade, and suggested that we make up a summer reading list…Well, as it turns out, it took her a long time and a few attempts to finish Harriet the Spy. She started A Wrinkle in Time and then set it aside because it just wasn’t interesting enough.” And later on, “Finally, though, prose is awesome. If you’ve never read The Westing Game, then you’re missing something really cool.”

about the prose options his daughter was given. A few quotes: “My wife mentioned a list of books that she had read by the time she was entering fifth grade, and suggested that we make up a summer reading list…Well, as it turns out, it took her a long time and a few attempts to finish Harriet the Spy. She started A Wrinkle in Time and then set it aside because it just wasn’t interesting enough.” And later on, “Finally, though, prose is awesome. If you’ve never read The Westing Game, then you’re missing something really cool.”

What I find a bit more problematic here is that while yes, Liu and his wife are encouraging their daughter to read prose alongside comics, they also might be falling into the trap of making a kid read books that they just aren’t interested in. Harriet the Spy, A Wrinkle in Time, and The Westing Game are classics all—but they’re classics from 1964, 1962, and 1979 respectively.

Are these titles embraced by today’s kids? Of course. But not all of them work for all kids, and I see a lot of parents trying to make their child read by making them read what those same parents loved when they were kids. It rarely works. Setting up a reading list might be a good way to organize a child who’s not inclined to read, but I’d say perhaps letting them choose one comic and one prose book of their own choice might work better. Both formats need to be in the mix (as do audio stories and visual stories like movies, TV, and video games, IMHO) in order to hone all of these skills, but I strongly believe that what those kids read should be their choice.

Esther: Robin, I think you brought up an excellent point (see me nod in agreement). I think some of the suggestions I make later on in this conversation might work for parents who want to share and expose their children to certain titles. It’s only natural to want to share what you love with your kids, the same way you share your love of certain foods or attractions; there’s no harm in trying to share certain titles.

Mike: Yep. We have a tried and true habit of forcing kids to read what we read when we were kids/teens. Sometimes the books weren’t so great. I think I liked (not loved) A Wrinkle in Time when I was a kid, but there’s much more out there now than ever before to explore.

Michael: Robin’s point is important. I’m all about getting my son to try new things, many of which are things I loved as a kid, but there’s a danger in getting too invested in what a child is reading or watching. David shares my love of superheroes, for example, but he’s not at all into the Tarzan books I couldn’t get enough of when I was his age. We should absolutely try to connect with children by recommending older books; we just have to be careful about taking it personally if the kid doesn’t dig them.

Michael: Robin’s point is important. I’m all about getting my son to try new things, many of which are things I loved as a kid, but there’s a danger in getting too invested in what a child is reading or watching. David shares my love of superheroes, for example, but he’s not at all into the Tarzan books I couldn’t get enough of when I was his age. We should absolutely try to connect with children by recommending older books; we just have to be careful about taking it personally if the kid doesn’t dig them.

Robin: I think that’s a great point, too, Michael—don’t take it personally! I frequently tell any person I recommend books to that I sincerely do not mind if they reject any or all of my recommendations. I will not mind if someone hates the book I love. I DO ask them to come back so we can try again. That way, we’ll eventually hit on the perfect book, and maybe find a few more titles in common along the way.

Jonathan Liu never said that comics aren’t “real” reading. That was just an attention grabber. But there are still many parents and educators who come up to me and say, “My child isn’t reading,” yet they’re holding a stack of graphic novels or they tell me that “Graphic novels isn’t real reading.” What do you, as graphic novel fans and avid graphic novel readers, tell parents and educators that comics aren’t real reading?

Mike: I think we’ll be hearing this for years to come. It is up to the parent to decide what they want their kids to read, but I do like to interject that the vocabulary in comics is still pretty high.

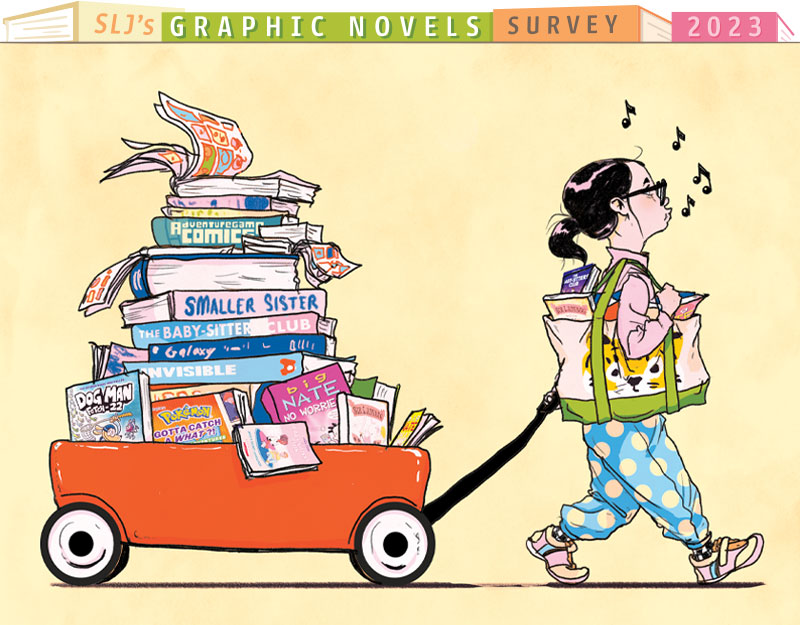

Lori: If it has words on a page, real or virtual, it’s reading as far as I’m concerned. But I wonder if we’ll be continuing to hear that in the years to come. We have a new generation of teachers coming out that grew up reading comics and graphic novels and see their value in encouraging kids to read, especially problem readers. I think the acceptance in schools will grow. My youngest daughter’s 8th grade English teacher allowed graphic novels and manga to count toward ROAR page counts. Higher education courses have used graphic novels to supplement prose novels as well. If there were anything to object to in comics as reading material, I might go with weak plots and stories, but even that’s changing.

Esther: I really thought I was done hearing “comics isn’t real reading.” I’ve  had comics in my school library for 10 years now. Like Lori said, it’s a whole new generation of teachers, but this year I heard it a few times and I just sighed. Mike mentioned the high vocabulary and I always turn to Kylene Beers’s book, When Kids Can’t Read, and show the page where she writes that reading comics teaches children new vocabulary … for a rate of every 1,000 words, reading comics is only second to Scientific Journal articles. Of course, I also explain that it’s a whole different method of reading.

had comics in my school library for 10 years now. Like Lori said, it’s a whole new generation of teachers, but this year I heard it a few times and I just sighed. Mike mentioned the high vocabulary and I always turn to Kylene Beers’s book, When Kids Can’t Read, and show the page where she writes that reading comics teaches children new vocabulary … for a rate of every 1,000 words, reading comics is only second to Scientific Journal articles. Of course, I also explain that it’s a whole different method of reading.

Michael: I don’t have a background in education, so all I can do is share my own experience. Comics were an extremely important part of my reading diet as a kid. They weren’t the only part, but I learned a lot of vocabulary from them. Anyone who says that comics aren’t “real” reading simply hasn’t been exposed to them enough.

Robin: Another way I turn this around is to ask parents to consider the world their kids inhabit: full of prose, certainly, but also full of movies, television, the internet, video games, and audiobooks or radio. With all of these ways of getting stories, kids need to learn how to parse all of these formats, and comics are included in that mix. Being able to comprehend how words and images work together as narratives, especially in the age of the internet, is vitally important to any child growing up. I admit, there are days when I want to yell to the rooftops that we’re actually doing kids a disservice by insisting they learn one way of understanding stories—in prose—and leaving them to their own devices when it comes to images, video, and the internet. Literacy comes in all shapes and sizes, and if we want kids to be smart, critical, and adept consumers of narrative, we need to help them understand how all of those formats work.

Eva: I was on a panel once where a speaker equated this to kids playing in a park. You’d never hear a parent shout, “Mary, you haven’t spent enough time on the swings! Go play on the swings for twenty more minutes, or no more slide for you!” The idea that every person has to like every kind of storytelling equally, or that one kind of reading or one way of processing information is better than another, is ridiculous.

In his post, Jonathan Liu mentioned that his daughter was taking the easy way out: “the middle school books she did want to read were page-turners: lots of pictures, simple vocabulary, action or jokes in every sentence.” I’m assuming he is referring to the hybrid novels, such as Diary of a Wimpy Kid, James Patterson’s Middle school series or Rachel Renee Russel’s Dork Diaries. This format has become wildly popular because it incorporates both prose and comics while filled with a lot of humor. Are these books taking the easy way out? Do you feel that children can’t or won’t eventually grow their reading to more challenging books or a variety of books?

Mike: I think the format is fun, light reading—and perfect for those readers looking for a quick escape. I think the upcoming Jedi Academy by Jeffrey Brown is pretty fun and sure to attract a lot of potential readers. I think there’s an audience for it and there’s no shame in inter-mixing your reading pleasure with the hybrid novels, comics, and prose.

Mike: I think the format is fun, light reading—and perfect for those readers looking for a quick escape. I think the upcoming Jedi Academy by Jeffrey Brown is pretty fun and sure to attract a lot of potential readers. I think there’s an audience for it and there’s no shame in inter-mixing your reading pleasure with the hybrid novels, comics, and prose.

Lori: I agree with Mike that these books are fun, light reading, but I don’t think a middle schooler enjoying them now means they will only want to read them forever. Reading tastes change, and things that a child is reading in middle school might not seem so appealing once they move up into high school. My oldest daughter enjoyed comics and manga more in elementary and early middle school. By late middle and high school, she wasn’t as interested, and was looking at prose books that fit her interests more.

Esther: I actually love the format, and it’s wildly popular in my school library. But this year I was starting to get concerned. Is it challenging enough? If this is what they read, will the kids be able to master the standardized tests? (New York is one of the first states to test to the new Common Core Standards. It was a tremendous pressure for teachers. The sample test for the 7th grade was a short story by Jack London that was extremely difficult.) I kept wondering how I can guide them to more “complex” tests. This is the pitfall, I believe, of working in a school. Because the side of me that is just a reading advocate kept saying, “Who cares. They’re reading!”

I agree with Lori that everyone’s reading tastes change. In my current life stage, I find that I need very quick reading books, because I have no patience for long drawn out books. I’m lucky to keep awake for more than three pages at a time! What they’re reading now isn’t an indication of what they’ll read as adults. Tastes change. Tastes evolve.

Michael: It’s a good question, and I suspect it’s different from kid to kid. Some kids may never develop a desire to read anything more than the easy stuff; others will graduate on their own. Kids like my son have to be nudged gently towards more challenging books so that they can experience the rewards of reading those for themselves. I’d never want to prohibit a child from reading something she enjoys, but I’m all for setting limits and encouraging growth.

For parents who are concerned that their children are only reading comics and want to help their children explore other formats and genres what suggestions can you offer them that won’t put a ban on reading comics?

Lori: Interest level. Find prose books that the child really enjoys and/or that  share stories or themes as the comics they are reading. My youngest daughter struggled with reading. She loves cats. We gave her the Warriors novels, and she devoured them, reading 400 pages in a week. I think a lot of people underestimate the power of interest.

share stories or themes as the comics they are reading. My youngest daughter struggled with reading. She loves cats. We gave her the Warriors novels, and she devoured them, reading 400 pages in a week. I think a lot of people underestimate the power of interest.

Esther: I think parents should possibly read a book together with their child. Either form a mini book group or actually read aloud to their child or read one chapter to them and have them read the next chapter to you. Parents can take turns with their children when picking out titles. Also, there are many incentives that parents can offer their children. One of the 7th grade teachers created a “book bingo” with her class. She created a board. Each box had another genre (and she lumped in graphic novels as a genre) and the children had to choose a row, column, or diagonal. So they had to read five books of varying genres. I could see doing some variation of that and offering my child an incentive if they complete the challenge. So while limiting comics to one day a week can work, I see other ways to expose kids to different types of reading.

Michael: I love both of those suggestions so much. The only thing I’d add is not to place too many restrictions on subject matter. While I’m all for encouraging kids to read more challenging text, like Lori said, it’s important that they be able to read about something they’re interested in. Nothing kills the desire to read faster than being forced to read something you think is totally boring. Related to that: We should maybe give kids permission not to finish a book they aren’t enjoying.

Robin: I definitely echo what Lori and Michael said: Interest is absolutely key. Kids need to read about what they are interested in in terms of subject, so if you can connect their interests to what they’re reading in prose, you’ll have a better chance of hooking the kid on reading in general. And, as I said above, that may mean going outside your own comfort zone in terms of what you once liked, or think they will like. Also, I would encourage everyone to consider novellas, nonfiction, short stories, plays and screenplays, audiobooks—there are so many ways to engage, and I think those of us who are novel readers tend to forget about the wide range of prose that’s out there!

Eva: I think it’s important to note that, according to the article, Mr. Liu’s daughter has always been a voracious reader and has only recently gone comics-exclusive. It sounds more like she doesn’t want to read more than a few pages without illustrations, not that she can’t.

I suspect she’s going through a period of comfort reading. Clearly she’s getting something from the book or she wouldn’t be revisiting. And with illustrated books, rereading is often warranted, particularly for prose-based readers like me, who miss things in the illustrations if they are engaged with the words. Rereading illustrated stories may actually be improving her comprehension.

Allowing her to choose her own books may help boost her enthusiasm for reading as she enters a grade level when many students begin to abandon recreational reading due to the increased pressures of homework, sports, or other extracurricular activities. Do I think her parents are wrong to only let her read comics one day a week? I think that might be a bit strict, but no. At least they’re allowing her to keep comics in the mix.

In his post, Liu mentions that if his daughter can’t sit and read more than a few pages without illustrations, she won’t be able to meet the standards she will be asked to meet in the coming school years. Given the national push of Common Core Standards, children are being asked to balance informational and literary texts. (Shifts in ELA and Literacy http://www.engageny.org/sites/default/files/resource/attachments/common-core-shifts.pdf) as well as build the level of complexity in their reading. What role do you think comics can play in this? Do you think comics and illustrated texts are hindering a child’s growth in reading?

Lori: Comics and graphic novels can be used to support many of the common core shifts. Comics can be just as informational as text, and can be used to engage readers in conversations about that information. Thinking that comics and illustrated texts hinder a child’s growth in reading will only take away another tool that could inspire child to step further into the world or reading. Common Cores are good first steps, but not all kids learn the same and that should be acknowledged.

Lori: Comics and graphic novels can be used to support many of the common core shifts. Comics can be just as informational as text, and can be used to engage readers in conversations about that information. Thinking that comics and illustrated texts hinder a child’s growth in reading will only take away another tool that could inspire child to step further into the world or reading. Common Cores are good first steps, but not all kids learn the same and that should be acknowledged.

Esther: Lori, I could not have said it better myself. Over the last year, I’ve been jotting down ideas on how to include comics into the common core curriculum. I don’t think Common Core excludes comics. And there are plenty of non fiction comics out there as well as complex fictional comics. Anyone who says there’s no room for comics in the Common Core is either not understanding the standards and the shifts or they are limiting their view.

Michael: I agree and just want to underline what Esther said about non-fiction comics and complex, fictional ones. The comics medium is vast and has many different levels. It’s a mistake to toss out the whole thing without understanding the diversity of reading experiences it offers.

Robin: Agreed! With everyone.

I would add that, as a kid who thought of the world in pictures first, words second, I think it’s vital to remember that people process information in so many different ways. Sometimes, for example, a visual explanation is the only way a reader will understand a particular scientific concept (I’m thinking of when I finally understood a bit more about Feynman’s contribution to physics in reading Jim Ottaviani’s biography and finally seeing Feyman’s work presented visually.) It all depends on how your brain works, and having all of the options, including visual options, can only help in comprehension and sophistication in my book.

Filed under: Roundtables

About Esther Keller

Esther Keller is the librarian at William E. Grady CTE HS in Brooklyn, NY. In addition, she curates the Graphic Novel collection for the NYC DOE Citywide Digital Library. She started her career at the Brooklyn Public Library and later jumped ship to the school system so she could have summer vacation and a job that would align with a growing family's schedule. On the side, she is a mother of 4 and regularly reviews for SLJ. In her past life, she served on the Great Graphic Novels for Teens Committee where she solidified her love and dedication to comics and worked in the same middle school library for 20 years.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

I think limiting it to one day a week is a strange way to do it. Limiting to one graphic novel a week I can (sort of) understand, but why interrupt your kid when they’re in the groove of a particular story?

Like many voracious readers, I have shelves filled with prose and comics I haven’t read. To get myself to read them, I personally set my own goal of trying to read either 200 pages of prose or 500 pages of comics a week. I’m so busy I rarely accomplish either, but the challenge works to make the comics page count seem a little daunting, and the prose count more manageable, all while checking some books off my “to read” list. Perhaps something like that would work to get children to diversify their reading? Or something as simple as regular library trips where they’re limited to 2 or 3 graphic novels but can take out as much prose as they want– allowing them to browse the stacks and pick the books that sound appealing to them and not try to “assign” them books.

But then again, I’m on the upper end of the Harry Potter generation– it seems a little foreign to me that there should be much struggle at all getting kids to read prose.

As a parent and as a librarian, I think I would try a different way to promote the reading of other formats and genres. But it’s a method. And might work for some children. Personally, what I believe works well is incentive and challenge. Now-a-days to get my little ones to get dressed fast we play “beat the clock.” It works like a charm. I bribe them to behave. And I’m not ashamed at my parenting methods. So why wouldn’t I bribe my child to try and read something they think they won’t enjoy? (Right now I don’t have to bribe them at all to read. It’s a punishment if I deny them their stories!)

I believe so strongly in reading aloud when kids resist longer texts, fiction and nonfiction alike. All three of my kids have gone through major comfort-reading/re-reading phases (and explain to me how the Clique books or the Twilight series are that much more challenging than Bone, Smile, or even the classic Marvel series?) and trying to force new titles on them rarely if ever works. Having a pile of potential read-alouds, including Agatha Christie and Terry Pratchett as well as titles recommended for YA? That’s an excellent way to keep my kids engaged with longer/non-sequential-art books.

One favorite read-aloud of the past year for us was Steve Sheinkin’s The Notorious Benedict Arnold — which I think shows that parents are both too soon to give up on read-alouds after a certain age, and not quick enough to try non-fiction books, too.

Jody, I just had to chime in here with a hearty yes! I listened to many, many stories as a child, both read to me by my parents as well as recorded on record (dating myself!) and on cassette. I had a particularly beloved version of Sleeping Beauty (read by Claire Bloom and with Tchaikovsky’s music throughout) that I listened to over and over again.

Listening to stories is yet another way to discover stories, and I admit to becoming an audiobook addict in my adult life (as well as a podcast addict.) There are many books I’ve found harder going in print (including Libba Bray’s Beauty Queens, Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimeaous books, and Le Carre’s Tinker Tailor Solider Spy) that I found engaging in audio. The audio doesn’t make me enjoy a book I wouldn’t otherwise, but it does provoke me to pay attention in a different way and, with the right reader, brings the story to life. Also, I very much agree on Notorious Benedict Arnold: both a fantastic read and a great reader in Mark Bramhall.

I agree Jody, some of my best memories is my mother reading books to my siblings and I. And It’s been a lot of years since 8th grade, but I probably will never forget Mrs. Aberbach reading the Tell Tale Heart by Poe aloud to the class.

My younger son is going to start college in one week. He started reading comics when he was in Kindergarten; he still prefers to read the comics format, but that didn’t stop him from doing well in Language Arts classes. He took AP English his senior year. He’s always been a good reader, has read a minimum of an hour a day since he was five years old. And he’s not the only one I know. One of my students is going to start high school in one week. As an 8th grader, he was first in his class; he’s always been a top student. He loves graphic novels, he loves prose fiction. His parents tried to get me to force him to stop reading Bone when he was in 3rd grade; I convinced the mother to allow him to read Bone and other graphic novels as long as he was also reading prose books. They started doing the same thing to their daughter, who was in 1st grade last year; she started reading books on her own in preschool, and last year she fell in love with the graphic novels. After the first month of school they didn’t allow her to bring home any more comics; she ended up borrowing mostly nonfiction books like the Guiness World Records books and other trivia compilations rather than any stories of substance. Interestingly, their middle son, who was in 3rd grade last year, seems able to read whatever he wants – he borrowed lots of graphic novels along with lots of fiction and nonfiction throughout the past year. He’s also a very good student. I grew up reading lots of comics along with lots of all kinds of books. When parents complain that reading comics isn’t real reading, I end up using myself as an example of someone who read comics and still reads comics and is a successful person. It doesn’t always convince them (hmmm …), but sometimes I can work a compromise with them.

Kat, I have to agree, that by reading comics, it won’t stop children from doing well. I remember discussing a particular student with a teacher. The student was an avid super-hero-comics reader. And the teacher commented on the student’s high vocabulary.

And there’s nothing wrong with a parent wanting their child to explore other sorts of reading either. But my motto is incentive and challenge not limitation.

I don’t see a need to limit my kids’ comic reading time. However, it is incumbent upon me to engage with them and share the joy that comes with reading a variety of genres. There’s time enough for both.

I’m a kid and I don’t really see the difference between reading a novel and alot of comics, it’s easier to get into the story with a comic and I’ve fallen in love with comic books, and I hated reading before I read my first comic.

I fans myself reading for around 2 to 5 hours a day just because of the wide range of comics I find online.

One time I spent 12 hours reading in one day, but I don’t recommend that as I could barely walk after.

So I would say for a parent, not to limit how many your kids read, but how long they read comics each day. If they are like me and never want to stop… Limit it to like 2 hours a day of comics, then do something active.

Maybe on weekends a bigger time limit.

*find* not fans

I’m a kid and I don’t really see the difference between reading a novel and alot of comics, it’s easier to get into the story with a comic and I’ve fallen in love with comic books, and I hated reading before I read my first comic.

I find myself reading for around 2 to 5 hours a day just because of the wide range of comics I find online.

One time I spent 12 hours reading in one day, but I don’t recommend that as I could barely walk after.

So I would say for a parent, not to limit how many your kids read, but how long they read comics each day. If they are like me and never want to stop… Limit it to like 2 hours a day of comics, then do something active.

Maybe on weekends a bigger time limit.