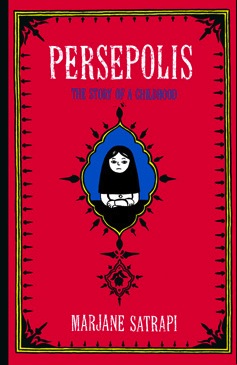

Roundtable: Removing Persepolis from Chicago classrooms

The recent removal of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis from some classrooms in the Chicago Public schools attracted a lot of attention. Although it first appeared that all the books were being removed, it turned out that the school district had had second thoughts about teaching it to seventh-graders, largely because of a single page depicting torture.

For this roundtable, I was joined by two of our Good Comics for Kids bloggers who have expertise in working with tweens and teens: Robin Brenner, who is the Teen Librarian at the Brookline Public Library in Brookline, Massachusetts, and Esther Keller, who is the librarian at JHS 278, Marine Park, in Brooklyn, NY.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Brigid: Does Persepolis seem like a good choice for 12- and 13-year-olds? In terms of the themes and storytelling, is this something seventh-graders can relate to, or is it over their heads?

Robin: As Persepolis follows the years from age 10 to 14 for Marjane, I do believe that this is a title that would engage 12- and 13- year old readers. Whether it should be taught in the classroom is a more difficult question for me to answer, as my main experience is a public librarian, and we have very different rules in terms of what we collect.

Looking at the other titles suggested on the Chicago Public School’s toolkit for teaching 7th grade, there are other similarly provocative titles included in their prose choices, including Monster by Walter Dean Myers (during which a teen is held in juvenile detention for his alleged participation in a robbery that led to murder) and Hole in My Life (Jack Gantos’s memoir of his tangles with the illegal drug trade and short stint in prison toward the end of his teen years). If these texts are indeed being taught to seventh graders, it seems unfair to pull out Persepolis for being any more shocking or for presenting tough ideas.

Ultimately, I think this kind of tale might even best be discussed in a classroom for students this age, rather than reading solo, precisely because a teacher is present to frame the work. Teachers can then help students understand the context for the work and deal with any questions or concerns they might discover in the reading. However, I could also say that it might be best read with an adult co-reader—whether that be a parent or a teacher.

Esther: From a collection development point of view, the book is reviewed as an adult or an adult/high school book. I did include it in my collection, but I remember that I was a bit hesitant, because the content is on the mature side. Then we had visitors come to our school and they asked me if I owned the title. I was a bit more relaxed about my decision after they seemed pleased that I had included it.

I view Persepolis as a title in the same category as Maus and Barefoot Gen. All are important titles. All tell about truths that we should be teaching students in middle school (and we do). But all the comics have some images that might be disturbing or difficult for a young audience. My gut tells me that this isn’t a title for 7th grade. I remind you, I’ve been working in a middle school for 10 years now. I might not be an expert, but I do know the age well. They’re not all that mature. And while I wouldn’t exclude it from a school library, I don’t know that it’s an appropriate classroom choice. But then again, I advocated for Maus to be taught in the classroom, and the same argument could be made for that title… So, I’m on the fence.

I’ll also add that these titles are rarely checked out by my students. They’re not hugely popular.

Robin, you mentioned titles included in the curriculum, Monster, by Walter Dean Myers, and Hole in My Life. I’ve always considered these titles a bit on the mature side, though again, they’re included in my library. But graphic storytelling is much more in your face than prose. Our brain might build a picture, but it can also gloss over the words the author is trying to give us as a defense mechanism. You can’t really do that with a comic.

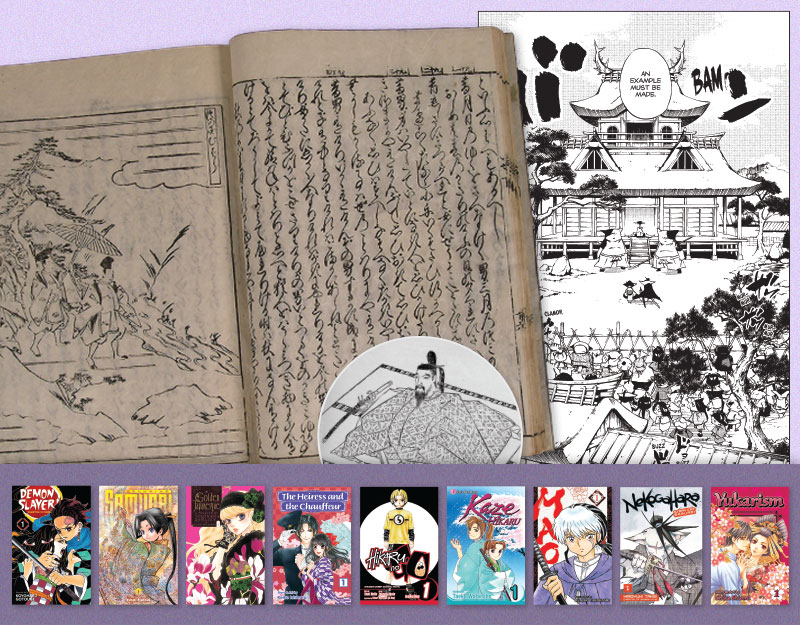

Robin: Esther, I do definitely see your point, and I know for many folks images have at least a very different, and immediate, impact that prose does not. A teacher colleague of mine says she explains it that it’s not that images have more impact, but they have impact faster. Prose gives us a little distance in understanding the words, but visual literacy is becoming (if not already is) just as important as prose literacy. Being able to parse and be critical of images is more and more vital, and more and more necessary to navigating the world. We are going to be confronted with images that are shocking or upsetting, and we are already exposed to so many images from childhood on. I am more and more convinced that being overly cautious about presenting difficult images to younger readers is a disservice to them. They desperately need to be able to understand and then think through the mechanisms of visual symbols, narratives, and media.

I also speculate that the gap of impact between words and images is changing or, at least, becoming equally important to learn about, in a world saturated by television, film, videogames, and comics. I know from talking to readers that some are more frightened by prose than images. For them, conjured images are more upsetting because imagination is specific to that reader’s fears, whereas presented images are concrete and less specific.

The substantial impact on a reader is precisely why Satrapi told her story in this medium. As with prose, readers gain empathy in reading stories told in the comics format, which may be why memoir is particularly powerful when presented in the format. For students in the US, Persepolis is such a strong example of a text providing a window (rather than a mirror) to teens’ experiences and is a vital text for expanding teens’ sympathy, empathy, and understanding of people outside their immediate world.

The question remains if in this case the schools are being overly cautious or appropriately cautious, but I would argue they are being overly so.

Brigid: Looking at the page in question, do you think one disturbing image should be sufficient to remove a book from a group of readers? To what extent does context mitigate that?

Esther: I think that’s an excellent point. It’s been a really long time since I read Persepolis, and I only read the first volume. I barely recalled this part. Looking at the images again, (they were published in second article linked above) out of context, it’s quite disturbing, but when I read the book, those images were a small part of a whole. In context they were less disturbing—though the ideas are disturbing and they are meant to be disturbing. After all, we are talking about the torture and murder of a citizen by his government. But as Robin said before, it’s one snippet of a story that’s over 300 pages long!

Robin: I agree that, as with any reading, it has to be taken in context, and this one image in a 300-plus-page book made up of many more panels and pages must be taken in context. One of the most frustrating aspects of any title being challenged is that one word, one scene, or one idea is often pulled out as the cited reason for the challenge. Leaving the word, scene or idea without any sense of the reason that item appeared in the narrative makes it impossible to judge its appropriateness. I also think of Persepolis as being disturbing at points, but truthfully so, necessarily so, for readers to understand and empathize with the story being told. I never felt it was excessive or gratuitous, and I don’t think that one image should be the cause of removing the entire book.

Brigid: I think one of the questions I always have when I look at a book is “Who is this for?” This book looks at life from a child’s perspective, and I think that is what makes it age appropriate. The page in question depicts violent acts but not in a gory or scary way. What’s scary is the society that Satrapi lives in, the society that commits these acts. And I think that Persepolis is written in a way that is very accessible to 12-year-olds. There’s nothing there they wouldn’t understand (except what the heroine herself doesn’t understand), and there’s a lot for them to relate to.

Esther: Brigid, while I don’t think that Persepolis isn’t accessible for 12-year-olds, I do believe it was written for adults.

Brigid: One interesting angle to this story was the distinction between classroom copies and library copies of the book—even as the books were being physically removed from classrooms, administrators were cautioned not to take them out of the libraries. How is the dynamic different between classroom and library books, from a policy and a user standpoint?

Esther: I think the biggest difference is choice. I don’t force students to borrow books from the library. Generally no teacher tells their students, “Johnny, you have to borrow such and such title.” They might say, “Johnny get a book today!” but they don’t force a specific titles on their students. In class they are forced to read whatever the teacher is telling them to read. So they don’t have the option to turn the title down if it’s too much for them. Readers always self censor, but in the classroom that choice is taken away from them.

Brigid: I agree, Esther, and I think that’s the key here. So how is this classroom challenge different from a library challenge?

Esther: If the challenge was to reverse itself on a curriculum decision, then I don’t believe it’s actually a “challenge.” I mean, in my school, we have rooms of class sets of novels we no longer teach. Are we censoring those titles? Or did we rethink those titles? Teachers get bored. Curriculum needs and standards change. Our student population changes. One year, a group of 7th graders might be super mature. The next year, the 7th graders might be very immature. So if students still have ready access to the title, is it censorship? Darius, in his article, said it so well! “But while we’re being clear, let’s admit that, while this action may constitute censorship, this probably wouldn’t have been an issue had Chicago curriculum not originally included and approved the graphic novel. Schools routinely make such decisions, determining grade-level appropriateness, and such decisions don’t tend to get a lot of attention. What can get a lot of attention is when a school seems to reverse itself, as is the case here. If you censor from the start, no one seems to care; it’s when you reverse yourself that howls of censorship tend to appear. “

Robin: I agree entirely with what Esther has said—there is a difference between censorship and collection management. I think that what is bothering everyone is that the title is being pulled after already having been taught and included for this age group and above. While we don’t know exactly what has happened, it does smack of the traditional challenge trope: One person raises an alarm not at the basic level (i.e. with a teacher) but at a higher level (i.e. an administrator), the administrator (without the immediate experience of the teacher and/or librarian who has worked with the challenged text) decides to pull a title, and everyone is left wondering why and how this happened, since it was not handled the way challenges are set to be handled—with a reconsideration process and often a committee of people making a decision rather than just one.

Brigid: Do you have any thoughts about what spurred this action?

Esther: I’m really confused as to what started this. Furthermore, I’m confused, because if you look at the original e-mail it looks like it says that it was directed at the libraries, not just the classroom. Even though I’ve read quite a few articles, I’m still about confused about this part.

Robin: I’m equally confused! I fear we may never know—I get the impression that a lot of this has been unfortunately worded and handled before it ever hit the papers, and now the various turnarounds on what had been directed and will be directed is just muddying what the original intent even was. I know the educators and librarians in Chicago must be desperate for clarification!

Brigid: What do you think of the way the school district handled this?

Esther: They’ve probably had better days. But the Chicago Tribune article indicates that the books are back in the library. And the matter was resolved pretty quickly, so I wonder if this was really a miscommunication. If not, perhaps it was very fast back-pedaling. But even so, I don’t think there was time for the books to leave the shelf.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Robin: For me, it’s a bit naive on their part to think that word of such an action wouldn’t spread, and spread quickly. I’m betting the instincts were good—to consider and perhaps re-evaluate a particular title for classroom use—but the way it was handled was confusing, alarming to many staff, and done too much in the shadows. At least with public forums during challenges, community members including educators, librarians, students, and parents are allowed to participate. When something is revealed to be happening behind closed doors, it raises everyone’s hackles and leads to damaging speculation on all sides due to a vacuum of reliable information.

Brigid: Julian Darius points out that schools decide to include or exclude books all the time; this incident attracted attention only because the district changed its mind once the books were in the classroom. Do you think incidents like this will lead school districts to make more conservative choices in future for fear of offending parents and having other books challenged?

Esther: Districts are already conservative. These days, I don’t know of a school that does not fear its parent body. Parents rule the schools, though I don’t think this incident was instigated by a parent. I think it was instigated by an ill-advised investigator. But I’ll tell you, I don’t think this title is meant for 7th grade. And I’d say 50% of these challenges are because of poor collection development policies.

Robin: I don’t think this is a new trend—I think schools mostly err on the conservative side and have for a good while. I believe the growing visibility of graphic novels in the past ten years has made them at once a vanguard type of title to include, and thus exciting and engaging for students and teachers alike, but also lightning rods for misunderstandings and stereotypes about the format causing more visible (and thus newsworthy) stirs within a community. I fear that when a graphic novel is challenged, the incident is reported more rather than necessarily happening more than challenges to other types of books.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Roundtables

About Brigid Alverson

Brigid Alverson, the editor of the Good Comics for Kids blog, has been reading comics since she was 4. She has an MFA in printmaking and has worked as a book editor, a newspaper reporter, and assistant to the mayor of a small city. In addition to editing GC4K, she is a regular columnist for SLJ, a contributing editor at ICv2, an editor at Smash Pages, and a writer for Publishers Weekly. Brigid is married to a physicist and has two daughters. She was a judge for the 2012 Eisner Awards.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Crafting the Audacity, One Work at a Time, a guest post by author Brittany N. Williams

ADVERTISEMENT

I was helping at a school library and found a book on wolves. It had very distirbing pictures of the butchery of wolves over the last 200 years. The book was about wolf re-introduction into the great northwest of the U.S.A. and explained how important wolves are to the enviornment. this is a K-5 book.Should a book about animal cruelity be shown to elemetary students? When do we explain to children about inhumanity in all its forms? What do we consider inhumane, only human torture? How do we know when they are ready to receive such info, to comprehend the meaning. A book with dead animals is exceptable fot K-5 yet middle school students shouldnt be made awhare of human torture?