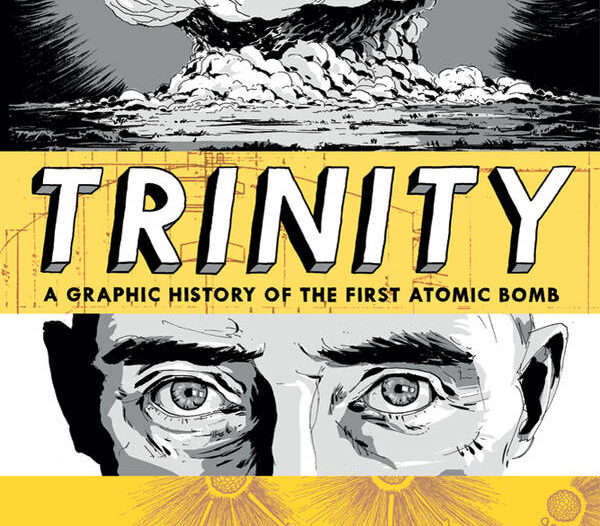

YALSA Hub Challenge: Trinity

Our fourth title from the YALSA Hub Reading Challenge is Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb by Jonathan Fetter-Vorm. Fetter-Vorm has found a solid career in creating nonfiction graphic novels with the publisher Hill & Wang, including the forthcoming Cartoon Introduction to World Civilization and a history of the Civil War. Trinity was highlighted as a Great Graphic Novels for Teens Top Ten title for 2013 and is in fact one of two titles about the history of the atomic bomb featured in the YALSA Hub Challenge, the other being Steve Sheinkin’s Nonfiction Award winner Bomb: The Race to Build—and Steal—the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon.

Our fourth title from the YALSA Hub Reading Challenge is Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb by Jonathan Fetter-Vorm. Fetter-Vorm has found a solid career in creating nonfiction graphic novels with the publisher Hill & Wang, including the forthcoming Cartoon Introduction to World Civilization and a history of the Civil War. Trinity was highlighted as a Great Graphic Novels for Teens Top Ten title for 2013 and is in fact one of two titles about the history of the atomic bomb featured in the YALSA Hub Challenge, the other being Steve Sheinkin’s Nonfiction Award winner Bomb: The Race to Build—and Steal—the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon.

As a refresher, the Great Graphic Novels for Teens Selection list showcases titles “recommended for those ages 12-18, meet the criteria of both good quality literature and appealing reading for teens,” and every year they also select the top ten titles from their longer list.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Robin: What did you think of Trinity as a way to introduce readers to the various aspects—scientific, political, societal—of the creation of the atomic bomb?

Esther: Hill & Wang has always done a great job with graphic nonfiction. But when I first started Trinity, I struggled with the science aspect of it. It was accessible, but I’m not a “right-side of the brain” sort of person. Literature and history is it for me.

But once I was past the science and the story delved into the history, I really did find the read fascinating. I’m not sure I ever really knew the entire story behind the atomic bomb. I definitely was not aware of the extent of the project in the sense that an entire town was built for the building of it. And you know, I never stopped to think about testing the bomb. How do you test an atomic bomb? It wasn’t discussed, but what sort of repercussions were there for the site that was tested? The effects probably weren’t visible for years on end.

Mike: I think the book’s topic is fascinating, but I too got a little bored by the science aspect in the beginning of the book. Once that part was done, I did find it interesting, but unlike other non-fiction graphic novels, I had a difficulty getting drawn into the book.

Caleb: I think Fetter-Vorm did a pretty astounding job of covering all of those rather big bases you mentioned—science, politics, society—in relatively few pages. What impressed me most is the way his narrative paralleled J. Robert Oppenheimer and other Manhattan Project scientists’ view of the bomb.

The book begins with the discussion of the science, the A-Bomb as a particularly challenging math problem in need of solving, and then once it’s used the book becomes more history than science, as Fetter-Vorm contextualizes it as a Pandora’s box that let loose many of the worst evils of the next 60 years or so. Likewise, we see Oppenheimer go from enthusiastic to ambivalent to desperately hoping for a silver lining to seemingly profoundly regretful.

It’s a fleet, stream-lined narrative, and certainly there are thousands of pages of prose on everything touched on in the book, but this is an excellent starting point for learning more about any of the events described within, and I think Fetter-Vorm was able to describe the science behind the bombs much more clearly and thoroughly than, say, any of the history teachers I’ve ever had.

Scott: I definitely agree with what has been discussed so far. The book is a successful introduction in that it provides an overview of a specific topic and, more importantly, generates interest for further reading. We librarians love books that inspire further reading! Luckily a handy list of resources including scholarly texts, other graphic novels, websites and films will point readers in the right direction. I have to admit I’m not usually a personal fan of non-fiction graphic novels but Trinity worked for me—it had a clear chronology of events, lots of easy-to-digest information about complex concepts, and there wasn’t a forced narrative that I often find to be the downfall of most of these kinds of books. Now I want to run out and read Barefoot Gen!

Robin: Perhaps it is precisely because I know a fair amount about the history and politics behind the atomic bomb (from my physicist parents and from other graphic novels, like Ottaviani’s Feynman or Fallout, all offering different perspectives), but I felt like Trinity was very dry. The explanations of science and the setting of the scene did work for me, but I kept putting the graphic novel down and wasn’t terribly inspired to pick it up again. I found myself wishing for a bit more of the personality of the scientists and politicians, the human side of the story, to back up the meticulous explanations. So for me, at least, while the title succeeded in its mission of giving a coherent overview, I never felt like I connected to the personalities nor really felt the tension of the story in a way I hoped to.

On to the next question: What do you think this title did best? What would you liked to have seen more of, if anything? What did you feel was missing?

Esther: I don’t enjoy nonfiction books, so the introduction of nonfiction graphic books has been great for me, because it allows me to delve into various topics without the “dense” narrative that makes it difficult for me to read nonfiction.

Caleb: I think it was most successful in telling the story of the first atomic bombs in the context of science as well as in the context of history, the former being something that isn’t usually emphasized, perhaps because it is so difficult to discuss and perhaps because it seems so much less urgent—You know, once the A-bomb goes from theory to fact, the question of what makes the apocalyptic weapon work doesn’t seem as a pertinent a question as who has such weapons, under what circumstances might they be used, and what would their usage do to us.

As a work of comics art, I think Trinity uses its blacks and whites to devastating effect in a few key moments, during the detonation of the bombs, scenes which are afforded much more space than the scenes of dialogue and character interaction.

I’m not sure it was really “missing” anything, but I suppose it would have been useful to end with some prose paragraphs explaining what became of key players after the events of the story. I often feel that way with non-fiction stories, as they don’t reach their conclusion in the open-ended way that fiction stories can.

Robin: I agree that the explanations of just what all these teams of scientists were trying to accomplish and discover were the best parts of Trinity. I never felt like I was struggling to understand the concepts and was happy to find a level of detail that felt in keeping with the level of the narrative. It wasn’t simplified, just clear, which is great.

I was a bit unsure by the end how much appeal this would have for teens. Yes, teachers and other adults will enjoy recommending it and deploying it as another option for learning about the history of the atomic bomb, but I wasn’t sure how many teens would pick it up due to their own curiosity rather than for an assignment. I’d love to hear from anyone who’s had teens respond to the title!

Scott: I would have to emphasize the clarity of the “science” of it all. I cracked open this book with little-to-no knowledge about the science of the atom bomb and I closed its pages knowing that I learned something, and something interesting! And of course the narrative or the history helped to make that learning feel less in-your-face educational. The seamlessness between the history and the science definitely made for an enjoyable read.

I agree with Caleb that I don’t think it was necessarily missing anything. The book is fairly text-heavy and reasonably so but I think that there could’ve been another edit to tighten up the exposition and dialogue just a bit.

Mike: I liked the focus on the scientists that were behind the Atom Bomb. Sure, some of it was conjecture, but I liked that they were portrayed with more humanity than they could have been portrayed.

Robin: Do you feel the comics format has an advantage for explaining more complex science and science history as shown in Trinity? I’m thinking of other examples from the world of comics nonfiction, including Jim Ottaviani and Jay Hosler’s works on everything from Richard Feynman to bees, and there seems to be a higher number of science titles in graphic format than other disciplines.

Caleb: Oh, definitely. I think a large part of the reason that Fetter-Vorm’s explanation of the science was so effective was because he was using comics to tell this story, and the medium’s unique marriage of words and pictures is perfectly suited to subject matter in which figures and graphs and illustrations aren’t side-bars but integral bits of story information. That is, parts of the book can read like a science textbook, only written in sentences made out of pictures instead of words.

Fetter-Vorm comes up with a few very good metaphors—I’m thinking of the dominoes lined up in the basketball gym especially—and by drawing them rather than just alluding to them, they are infinitely more real and relevant.

Scott: Absolutely! I especially loved the diagrams for the actual bombs themselves. I always wondered how those worked. Fascinating!

Mike: For whatever reason, we’ve been treated to more science non-fiction than other forms of non-fiction. I think it’s great, but non-fiction is at its best when done visually. It can be a little dry if done the wrong way. I think the title was effective, but it’s a little dry for my taste.

Robin: One of the harder aspects of creating nonfiction graphic titles is that they are often not allowed as research sources for classroom work—teachers may be fine with their students reading them but generally don’t rank them as substantial as prose works. Hill & Wang has, over the years, worked very hard to make their titles well-presented and carefully researched. Do you think students would be able to use Trinity in their research? Is that its purpose—or is it more recreational nonfiction?

Esther: I think this could be an excellent addition for classroom use. I can see a history teacher using this to support the curriculum and make the story come alive.

Caleb: Well, one nice thing about the book is the bibliography of books and other resources Fetter-Vorm used in making the comic presented at the end. So even if Trinity isn’t something a kid could use when putting together a report, it is a nice summary of several aspects of a big, somewhat difficult story, and one that comes complete with a roadmap for where to look for other books you can cite in your paper.

Scott: I agree with both Esther and Caleb but I think this book definitely has recreational nonfiction applications as well. There is a serious lack of non-fiction books in graphic novel form that present engaging topics that would make readers who tend to go for non-fiction to pick it up. I think non-fiction graphic novels is a big realm that really hasn’t been explored yet.

Caleb: What did you guys make of the artwork? While reading the sections diagramming what goes on in and around atoms, I thought that it might have been easier to read in color, but the subject matter and the setting really makes black and white art appropriate.

Scott: I think the artwork does the job here. I think black and white artwork lends itself more to non-fiction because it’s clean and concise. I think the addition of color may actually detract from the delivery of information here because it may bog down the page or you might just end up with a book full of greys and browns. Maybe some oranges, reds and yellows for the atomic explosions. I think what’s key here are the panel layouts, which are easy to follow and clear for the reader.

Robin: I did find myself missing color a lot. The images were very well done, given the limits of black, white, and grey, but there were a lot of times when I really wished there was also color. It did feel like it was missing to me, rather than deliberately done in black and white (a la Persepolis). I know that none of the Hill & Wang titles, to my knowledge, have been done in color, and that it’s likely a budget concern, but I missed seeing the landscapes and the further emphasis that diagrams might have had with a full color spectrum deployed.

Mike: I would think color would have been more striking for me, but if Hill and Wang has specific settings for their graphic novel line and color isn’t a feasible option, then there’s not much we can do about it.

Caleb: Did the book strike you as objective, or did Fetter-Vorm seem to have any obvious biases or agendas to what he chose to include and what emphasis he gave it?

I’m two generations removed from the one that fought World War II, and I understand many of the moral questions of the era seem settled, but I was struck by some of the facts given to justify the use of the bomb against Japan and the fact that they could be interpreted both as saying the U.S. was right to use the bomb because it ultimately spared more lives and that the fire-bombing of Japan previous was so insidious already that, as evil as the bomb might have been, we were already pretty neck-deep in such evil.

Scott: I didn’t really get a huge sense of bias. I do believe Fetter-Vorm did a good job at portraying the precarious position the world was put in with the development of the atomic bomb. He illustrated how secrecy, paranoia and ultimately destruction “helped” in the short term, but in the long term deeply complicated relationships between countries.

Robin: I also felt like it was relatively even-handed. Having just watched the Oliver Stone documentary series on the same decisions (which clearly does have a bias of its own), I think that the issues highlighted are true to the time and place. Justification of technological advancement during war is complex and, shall we say, fraught, and given the speed at which the events are being covered, I think Fetter-Vorm does a decent job of representing different angles.

Filed under: Graphic Novels, Young Adult

About Robin Brenner

Robin Brenner is Teen Librarian at the Brookline Public Library in Massachusetts. When not tackling programs and reading advice at work, she writes features and reviews for publications including VOYA, Early Word, Library Journal, and Knowledge Quest. She has served on various awards committees, from the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards to the Boston Globe Horn Book Awards. She is the editor-in-chief of the graphic novel review website No Flying No Tights.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT