Question Tuesday: Graphic Biographies too fictional?

I work in a public library system, and a staff member recently voiced concerns about fictionalized dialogue in graphic novel biographies. This person feels that the presence of that dialogue should exclude them from our biography collection, as all books contained in that collection are books of fact, not imagination.

Have you encountered such concerns before? If you do collect graphic novel biographies in your professional capacity, is the presence of fictionalized dialogue a factor you consider when making purchase decisions? And do you know of any review guidelines for biographical graphic novels?

– a public librarian in the U.S.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

This question prompted an discussion of how we librarians think of biographies, nonfiction, and format. I had my own ideas about how to consider graphic biographies, but I also invited my colleagues at Good Comics for Kids to chime in with their thoughts on the question so we’d have a multitude of perspectives.

My instinct is that fictionalized dialogue is not enough (in most cases) to invalidate a graphic novel biography. Every biographer makes decisions about what they portray, and how they show their subject’s state of mind, and while they may or may not construct dialog, they do write description and narrative that affects what the readers understand to be true. What they choose to include or leave out affects the book’s tone. I feel like any biographer’s narrative and point of view would have as much potential to skew the truth as using constructed dialog to tell a nonfiction story. Similarly, in memoirs writers recreate scenes and dialog (and may well be debated by the other participants of their lives), so I personally do not see this as a barrier to considering graphic novel biographies as valid biographies.

When I asked my colleagues here what they thought, Scott added, “…I think there’s ultimately an element of ‘fictionalization’ in any biography. I wonder if [we] would consider a biopic to be not a true biography, also. It’s pretty much the same thing as a graphic novel with dialogue.”

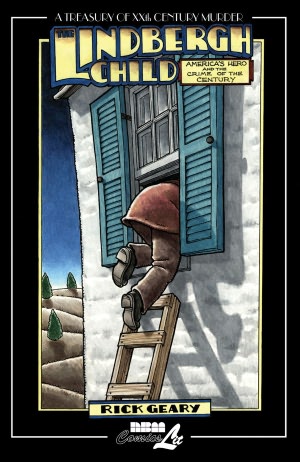

Eva chimed in with a Children’s librarian perspective: “…I’m used to seeing non-fiction that has been condensed, squished to fit, or where the author has fit him/herself into the narrative. So some dialog that has been worked to fit mood, intent, etc., wouldn’t phase me a bit. There aren’t many non-fiction graphic novelists out there who can make a story work with no dialog. I think Rick Geary is the exception to the rule.” Geary, in his Treasury of Victorian Murder and Treasury of Twentieth Century Murder series, uses very little dialog and instead depends on short prose sections per panel to report on the true crimes he covers.

Eva chimed in with a Children’s librarian perspective: “…I’m used to seeing non-fiction that has been condensed, squished to fit, or where the author has fit him/herself into the narrative. So some dialog that has been worked to fit mood, intent, etc., wouldn’t phase me a bit. There aren’t many non-fiction graphic novelists out there who can make a story work with no dialog. I think Rick Geary is the exception to the rule.” Geary, in his Treasury of Victorian Murder and Treasury of Twentieth Century Murder series, uses very little dialog and instead depends on short prose sections per panel to report on the true crimes he covers.

As graphic novels are made up of images (in place of a lot of prose description) and dialog, I can see why someone might be concerned about the validity of dialog. I’ve also known people to be concerned about the content of images, as with George O’Connor’s Journey into Mohawk Country. In that case, the text is word for word a complete primary source (a diary of a 1634 Dutch trader) but the images add to the story, not always strictly narrating what the diary includes. So is it a primary source? Or not?

As graphic novels are made up of images (in place of a lot of prose description) and dialog, I can see why someone might be concerned about the validity of dialog. I’ve also known people to be concerned about the content of images, as with George O’Connor’s Journey into Mohawk Country. In that case, the text is word for word a complete primary source (a diary of a 1634 Dutch trader) but the images add to the story, not always strictly narrating what the diary includes. So is it a primary source? Or not?

Our own editor Brigid also brings up graphic biographies that take a different tack in depicting their subject. “I have seen a couple of graphic novel biographies that approach the subject sort of sideways by showing them through the eyes of a fictional third party, like Satchel Paige: Striking Out Jim Crow and Amelia Earhart: This Broad Ocean. In that case the fictionalization is explicit.”

Our own editor Brigid also brings up graphic biographies that take a different tack in depicting their subject. “I have seen a couple of graphic novel biographies that approach the subject sort of sideways by showing them through the eyes of a fictional third party, like Satchel Paige: Striking Out Jim Crow and Amelia Earhart: This Broad Ocean. In that case the fictionalization is explicit.”

I do think it very much depends on the book. There are some graphic novelists who are meticulous in adding notes to their books to make sure readers know the source of their information — Jim Ottaviani is most exhaustive about this. Check out his notes for the book Fallout, his history and biography of Robert Oppenheimer.

Brigid agrees that notes and references vital to a good graphic novel biography: “Every writer has to pick and choose what they are going to include, as well as the sequence in which they set out the facts. What is kept in and what is left out can strongly influence the tone of the finished book. In the case of graphic novel bios, you really have to have dialogue—otherwise the book will be dull—but the author should clarify somewhere whether the dialogue is documented or reconstructed, as they often do in prose books.”

Brigid agrees that notes and references vital to a good graphic novel biography: “Every writer has to pick and choose what they are going to include, as well as the sequence in which they set out the facts. What is kept in and what is left out can strongly influence the tone of the finished book. In the case of graphic novel bios, you really have to have dialogue—otherwise the book will be dull—but the author should clarify somewhere whether the dialogue is documented or reconstructed, as they often do in prose books.”

Scott also thinks the limitation of the format should be recognized. “In terms of review guidelines – I would assume that strong research would be essential and even better with lots of notes and references. I think of something like Zach Worton’s The Klondike in which he admits the areas of the book where he had to piece together a scene based on historical facts in order for it to work. I think admitting the limitations of the form is also essential for a work to be taken seriously.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Esther also commented, “I don’t believe I’ve ever read a biography that actually uses fictionalized dialogue, but I don’t know that it has to exclude it from the biography section. That said, a compromise might be to just put in the proper dewey section. i.e. something about George Washington can be in 973.7, etc.” This could be a solution for librarians who feel a title isn’t quite a biography but still allows readers to discover more general information.

Esther also commented, “I don’t believe I’ve ever read a biography that actually uses fictionalized dialogue, but I don’t know that it has to exclude it from the biography section. That said, a compromise might be to just put in the proper dewey section. i.e. something about George Washington can be in 973.7, etc.” This could be a solution for librarians who feel a title isn’t quite a biography but still allows readers to discover more general information.

The majority of the graphic novel biography writers do exhaustive research, and I trust them not to invent dialog untrue to the circumstances or history they’re presenting. In terms of getting a reader interested in someone’s life, I think graphic novels have a strong place in engaging readers.

I would, however, leave it up to teachers to judge a particular graphic novel biography as a strong enough source for a paper, again depending on the notes and research in evidence. I would also trust biographies with further notes and obvious research more than I would a book that doesn’t cite it’s sources or discuss the limits of the format.

What do you think, dear readers? Have you pondered what makes a graphic nonfiction title nonfiction? Where do you draw lines?

The Good Comics for Kids Question Tuesday column is here to do one thing: answer your questions! To send in your questions for the next Question Tuesday, please go to our form here or send out a tweet to me at @nfntrobin or to all of us at @goodcomics4kids. We will endeavor to answer as many questions as possible in our weekly column. All questions are due in by Friday at midnight so we’ll have a chance to write up the answers for the next week.

Filed under: Question Tuesday

About Robin Brenner

Robin Brenner is Teen Librarian at the Brookline Public Library in Massachusetts. When not tackling programs and reading advice at work, she writes features and reviews for publications including VOYA, Early Word, Library Journal, and Knowledge Quest. She has served on various awards committees, from the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards to the Boston Globe Horn Book Awards. She is the editor-in-chief of the graphic novel review website No Flying No Tights.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

This is a great question! I’m a public librarian and we don’t buy many (really any) graphic biographies at my library due to lack of interest, but I think they are a fantastic teaching opportunity in school libraries. It seems like there are tons of ways to incorporate them into writing lessons for the reasons above (you can discuss all sorts of authorial choices). It would be interesting to compare graphic biographies with fictionalized accounts of famous peoples’ lives, such as Zora and Me.

Great article! I have also thought a lot about this topic, and while I think that graphic bios are a lot of fun to read and a great introduction to historical figures for kids, I’m always hesitant to give them to kids coming in for resources for papers because the books present the fictionalized dialogue as real dialogue. If I was a young child reading these books I don’t know that I would necessarily realize that the quotes aren’t real, and we as librarians can’t assume that the parent will be there to explain this, or that the parent will even realize that the quotes aren’t real. Children are encouraged to use quotes in their work, AND the fictionalized quotes in these biographies are usually much easier to comprehend than the real quotes, so I imagine a child choosing between real quotes from a biography and the fake quotes from one of these books might be tempted to use the fake quotes. Agree/disagree?