Are all Comics for Kids?

Recently, after noticing it was nominated for a National Book Award for Young People, I read David Small’s Stitches. While I very much enjoyed this book, I just felt it wasn’t actually written for young people. Some might enjoy it, but this isn’t necessarily a comic that is for kids or teens. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one who thought so, because I missed this story in Publisher’s weekly, which explains that Stitches was nominated into its category by the publisher. (I was trying to clarify if the category was for books written for teens as opposed to books with teen interest. It makes a huge difference.)

In the same vein, though not the same case, I wondered about the story in South Dakota – where a middle school pulled Ariel Schrag’s Stuck in the Middle: 17 stories of an Unpleasant Age. Would the book have had the same fate in a high school?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Is the problem that all comics are considered children’s books? How do we combat that perception? What does make a comic kid/teen friendly?

My friends at good comics chimed in with their thoughts on this topic.

Robin: I had been waiting to comment on this discussion until I was able to read Stitches myself (and it was a good push to read it!). There are a number of issues involved in the National Book Award nomination, as well as the problems surrounding Stuck in the Middle: 17 stories of an Unpleasant Age.

One of the biggest issues with awards and graphic novels, thus far, is that it is still remarkable when graphic novels are considered for any literary award that is not expressly for sequential art. I know readers are still occasionally startled to realize Maus won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s also telling that, in 1991 when Neil Gaiman’s “A Midsummer’s Night Dream” Sandman issue won the World Fantasy Award for best short fiction, the rules of said award appeared to shift so that comics were eligible only for the Special Award Professional category. This essentially made it so that no comic could win short fiction again. Comics and graphic novels are almost the new “it” thing to include in literary awards, and while I am glad to see the format gaining ground and recognition outside of the comics industry, I fear their inclusion is considered a curiosity rather than a natural progression.

readers are still occasionally startled to realize Maus won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s also telling that, in 1991 when Neil Gaiman’s “A Midsummer’s Night Dream” Sandman issue won the World Fantasy Award for best short fiction, the rules of said award appeared to shift so that comics were eligible only for the Special Award Professional category. This essentially made it so that no comic could win short fiction again. Comics and graphic novels are almost the new “it” thing to include in literary awards, and while I am glad to see the format gaining ground and recognition outside of the comics industry, I fear their inclusion is considered a curiosity rather than a natural progression.

Stitches being included in the Young Readers category brings up different concern: how the category is defined. Young Readers as a category seems to include everything from books for toddlers up through works for teens. Leaving aside what a huge range that is and how it might be unfair to judge all those works in the same category, the objections people raise in the Publisher’s Weekly article echo many of mine: a graphic novel is not, inherently, intended for young readers. Stitches, to me, is a title  that may have teen appeal, but seems to me most intended for adults. I can’t help but be skeptical, and echo Chasing Ray’s comment that perhaps Stitches was submitted for the Young Readers category because it stood a better chance to win in that category. Would Stitches appeal to some teens? Yes. Is it a teen title? No, not to me. To be perfectly blunt, Stitches is a searing, beautifully wrought memoir, and that is the particular kind of graphic novel that is currently considered award-worthy. I’d be much more impressed if a graphic novel that was not a memoir made it on to the consideration list.

that may have teen appeal, but seems to me most intended for adults. I can’t help but be skeptical, and echo Chasing Ray’s comment that perhaps Stitches was submitted for the Young Readers category because it stood a better chance to win in that category. Would Stitches appeal to some teens? Yes. Is it a teen title? No, not to me. To be perfectly blunt, Stitches is a searing, beautifully wrought memoir, and that is the particular kind of graphic novel that is currently considered award-worthy. I’d be much more impressed if a graphic novel that was not a memoir made it on to the consideration list.

Now, the age range question always makes me remember that we librarians think about age categories and ranges a lot more than most folks, even most readers. We all know how often parents come in insisting their ten year old reads phenomenally and is definitely ready to read Dickens. I also have had countless adults tell me that all teen literature is fluff and there’s nothing literary about any of it. We spend every day, in ordering titles, thinking about where they might best appeal and where to place them in our collections. The majority of the public never sits down and thinks too hard about just who the intended audience for Harry Potter actually is, or just why Twilight works so brilliantly for thirteen-year-old girls.

The only time the general reading public seems to concern themselves with age appropriateness is when there is something they consider inappropriate for the age, as with Stuck in the Middle. Many adults I know have blocked out the unpleasant or startling aspects of middle school, and tend to spend the rest of their lives ignoring what a complicated and difficult time it can be. Stuck in the Middle, when I read it, felt particularly truthful about the stress and cruelty of middle school. When adults object to such titles, appeal is never considered an important part of the equation, just what’s appropriate for readers (as if they are part of some homogeneous group.) There’s a big part of me that wonders if the kids in the middle school themselves were asked if the book was relevant to their lives, then we’d have a different answer to where it belongs. This is why, whenever I’ve had to consider a title as for an age range, I go to readers in that age range as much as possible and ask them what they think. I know as an adult I’ve lost track of what was great (and what was boring) when I was ten, or thirteen, or sixteen. That helps me answer the question of what makes a title for a teen or a child – if THEY like it.

The only way to combat the perception that all comics are for kids, to me, is fairly simple. Stop acting like they are. Start including adult titles in adult awards lists. Advocate for every library in the country to have graphic novel collections in their adult sections, not just in their teen and children’s sections, and make it abundantly clear that it’s not just because the content is “mature” but because the intended audience for these works is and always was adults. Educate the public by explaining that comics are like any other format and contain works for all age ranges and niche audiences. When we start categorizing books by what they don’t include (problematic content) and forget about who they appeal to most, then we’ve lost track of the point of age demarcations. We are supposed to be recommending books appealing to those readers, not just books deemed suitable for their tender minds.

Eva: I don’t want to get too involved in this discussion since Stitches is on the nomination list for GGNFT, but I want to chime in here in support of something Robin said. I try really hard when reading for selection lists to remember back to who I was at whatever age for which the book is being marketed. I know I’m not the target audience for something like Twilight or Alex Rider or Ultra Maniac, so I need to get back to the thirteen-year-old me who was the target audience for those books. This isn’t always easy to do and I had a hard time with Stuck in the Middle. I thought it was great and great for older teens who had survived middle school, but I wasn’t sure it was great for younger teens. As Robin said, the stories are harsh, cruel, and reek of the horribleness of middle school.

For the past three years I’ve held “read and review my graphic novels and I’ll let you eat snacks in the teen room” days at the library, where teens are invited to read any of the books on my cart of nominated titles, provided they’re willing to fill out a short questionnaire telling me what they thought about the book when they’re done with it, whether they finish the whole book or not. When a 12-year old picked up Stuck in the Middle, I kept an eye on him, watching for telltale body language, signs of discomfort or impatience. Max was completely engrossed in the book. He read it from cover to cover, not once stopping to refill his snack bowl. When he returned the book to the cart, I casually asked Max what he thought of the book. He told me it was perfect. “That’s exactly what my school is like.” he said. And that’s all I needed to hear. As librarian Josh Westbrook so famously posted, “Kids are living stories every day that we wouldn’t let them read.” While Stuck in the Middle may resonate more with older teens, the book is also great for younger teens. They are the ones who are living through middle school and dealing with the issues illustrated in the book. I wonder if I had trouble putting myself back into my 12-year-old self to read this book because what I really wanted to do was block out those middle school years altogether.

Esther: I’m tempted to re-read Stuck in the Middle, but I distinctly remember not enjoying the title all that much. Not because it made me uncomfortable, but because it didn’t grab me. That said, I do remember thinking it was an accurate portrayal of middle school life, and yet, as a middle school librarian, I still felt it was not an appropriate title to add into my collection. Especially as the demographic of my school changes, and our students are becoming more and more age appropriate (it’s so refreshing to have 11-year-olds who act like 11-year olds!), I would still say the nature of the title makes this more appropriate for a high school audience. (Though the reviews do not back up my gut feeling. Reviews clearly label this as a title appropriate for Junior High school – grades 7-9).

Yet, in my opinion, Stitches isn’t a title written for young people, though not for the same reason that Stuck in the Middle isn’t for middle school. I think it goes to the author’s intent. And I think author’s intent often “shines” through his/her book. When reading Ariel Schrag’s Stuck in the Middle, while it was a memoir in nature, it always felt like it was for the young reader, while somehow, when reading Stitches, I always felt that it was the author looking back from the adult POV. I felt he was “talking” to the adult reader. Not the teen.

Robin, you brought up an excellent point about how librarians consider content a lot more than the average person. It’s part of our nature– since collection development is such an integral part of our jobs– to consider whether books are too mature for a particular audience. And we don’t only consider sexual situations and violence, but also thematic content. A non-comic example would be Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson. Most reviewers thought this was for 8th grade and up, and the book is not at all graphic in nature. Rather the themes are heavy. Since comics are much more visual, they do come under attack a lot faster than a prose novel. It’s easy to peek over a child’s shoulder and see a picture popping out at you, where the words might not jump at you as fast.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

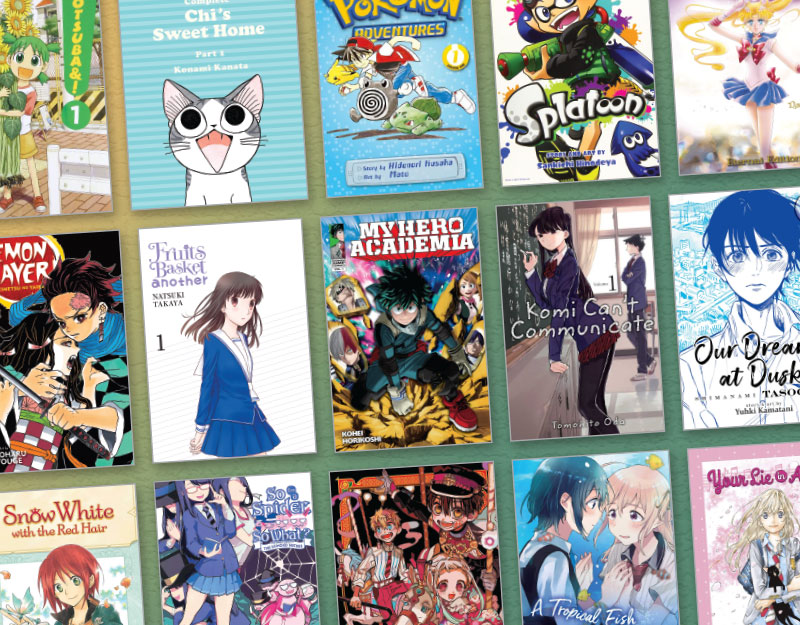

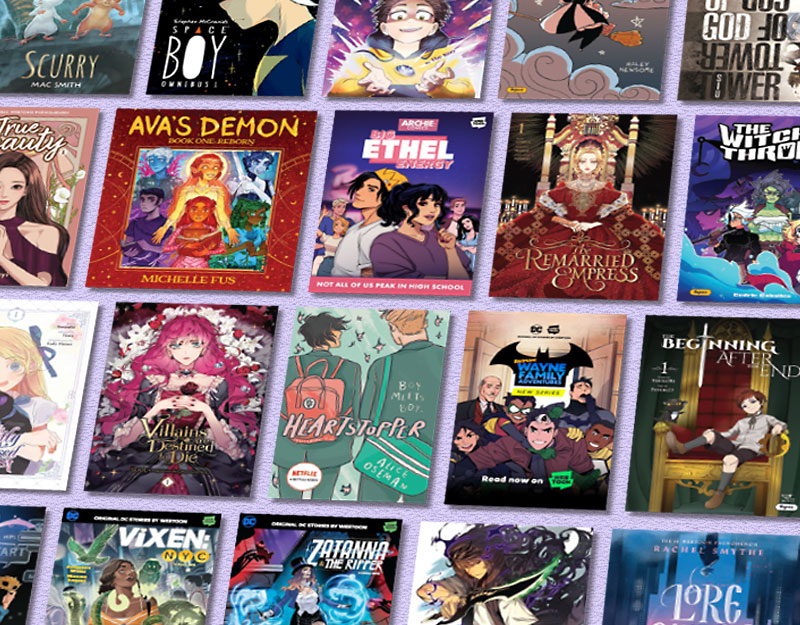

But the real problem, in my opinion, is that the perception is that if it’s a comic, it’s for kids. And that’s just not true. Those of us who are avid readers of comics know that there are comics for kids and comics for teens and comics for adults. The casual reader or the person who just knows they exist and doesn’t care to read them probably doesn’t realize the distinction. And Robin, you’re right. By sticking a book like Stitches in the ‘young people category’ it fosters the perception that all comics are for kids. In this case, it was the publisher who helped foster this image by submitting the title into that category. I do think there are teens who will like this book. Just like some teens like to read Nicholas Sparks. That doesn’t mean Nicholas Sparks writes for teens. He just writes adult books that teens will like. And yet, I never saw a Nicholas Sparks get nominated for a teen award.

Kate: Esther raises an important issue about context: it’s easy to get incensed about “adult” content (e.g. nudity or violence) in a comic for younger readers, but harder to assess the role that shocking images might play in the greater story, or assess their impact on the intended audience. The recent controversy in Wicomico County, Maryland – in which a parent objected to the presence of Dragonball in her nine-year-old son’s school library – is a good illustration of the problem. Akira Toriyama, Dragonball’s creator, is generally considered a children’s author in Japan; in the US, however, most of his licensed works have earned a Teen or Teen Plus rating for their bawdy humor. It’s a shame that in the rush to remove Dragonball from library shelves, none of the politicians decrying it took the time to look at the objectionable content in context. If they had, they might have realized that many of the images that they were categorizing as “pornography” were, in fact, exaggerated depictions of normal behavior among young children who are just becoming aware of the anatomical differences between boys and girls. These images aren’t meant for adult titillation; they’re meant to elicit laughs from kids who are old enough to remember that stage of their development. I’m not arguing that Dragonball is right for all kids, or for nine-year-olds in general, just that adults can be awfully puritanical about material that suggests that children are curious about gender and sexuality.

For me, the Dragonball controversy points to the bigger issue about a lot of kids’ comics: they come saddled with adult agendas. On the one hand, we want them to be serious, literary, and timely; if a kid is going to read a comic, shouldn’t be on par with the best young adult literature? On the other hand, we’re so worried that kids will be prematurely exposed to adult material that we’re hopelessly fixated on the wrong things. Kids can handle an occasional blue word or naughty joke; what they may not be ready to handle are heavy-duty, issue-driven stories that use young protagonists to explore adult themes. Stitches and Stuck in the Middle are right for some teens, but they’re not young adult books per se, any more than The Lovely Bones or She’s Come Undone — two titles I’ve seen on high school reading lists — are true works of YA fiction.

The other big issue is reading level. In our desire to protect kids from adult content, we often forget that the words can be just as inappropriate for young readers as the images themselves. I’ve reviewed many comics that have an “All Ages” rating that would be utterly mystifying to grade-school kids, owing to the sophistication of the syntax, the vocabulary, or the cultural references. I’d love to see more publishers follow the example set by Toon Books; the editors worked with educational specialists to ensure that their scripts were suitable for beginning readers. And if that isn’t feasible, it would certainly be helpful if publishers made a more concerted effort to provide information about the reading level, rather than assuming that comics without nudity, violence, or swearing were “for kids.”

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Esther Keller

Esther Keller is the librarian at William E. Grady CTE HS in Brooklyn, NY. In addition, she curates the Graphic Novel collection for the NYC DOE Citywide Digital Library. She started her career at the Brooklyn Public Library and later jumped ship to the school system so she could have summer vacation and a job that would align with a growing family's schedule. On the side, she is a mother of 4 and regularly reviews for SLJ. In her past life, she served on the Great Graphic Novels for Teens Committee where she solidified her love and dedication to comics and worked in the same middle school library for 20 years.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

A category for graphic stories was added to the Hugo Awards last year after much debate amongst fans. One of the issues discussed was the collaborative nature of such works. When Neil Gaiman won the World Fantasy Award he made of point of insisting on equal billing for his artist, Charles Vess. With regard to the Hugo, many of us felt that a separate category was appropriate in order to encourage fans to consider both the art and the story when casting their votes.

But it is a complicated issue. I was recently involved in launching a set of awards for translated science fiction and fantasy. There we decided to lump graphic stories and short fiction together because at this stage we can’t afford another category and we don’t want to exclude the large quantity of manga that gets translated each year.

The issue of separating the artist from the writer in a graphic novel is a tricky one, since both the words and the artwork is vital in the creation of the story. You can’t have one without the other.