Review: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Nos. 1-4

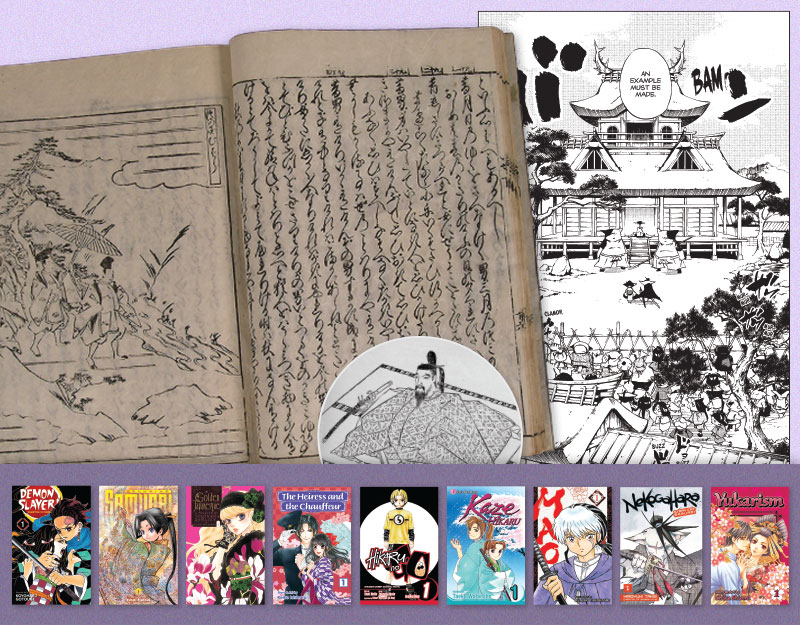

Since its debut over one hundred years ago, Frank L. Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) has enjoyed phenomenal popularity, both in its original form and in hundreds of adaptations, from a Broadway musical (1902) and silent film (1910) to a Nintendo role-playing game, a 52-episode anime (1986), a soulful revue (1975), and, of course, an MGM vehicle for the young Judy Garland (1939). The first Oz comic appeared in 1904. With a script by Baum and drawings by Walt MacDougall, Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz ran for nearly one year in newspapers around the country. The success of this first Oz comic inspired dozens of subsequent projects, from a competing strip by original Oz illustrator W. W. Denslow (1904) to a manhwa version featuring clones and cyborgs (2006 – present). Though Marvel has published several Oz comics, their latest, the eight-issue Wonderful Wizard of Oz, is notable both for its fidelity to Baum’s first novel and for the beauty of Skottie Young’s art.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Nos. 1-4

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Nos. 1-4

Story by Eric Shanower, Art by Skottie Young, Color by Jean-Francois Beaulieu

Age Rating: All Ages

Marvel Comics, 2009, ISBN 7-59606-060603

32 pp., $3.99

The first four issues cover familiar territory: a cyclone carries Dorothy and Toto from Kansas to Oz, depositing their farmhouse atop the Wicked Witch of the East and liberating the Munchkins in the process. After donning the Wicked Witch’s magic slippers, Dorothy sets out on the yellow brick road, acquires her famous traveling companions, endures a variety of trials—river crossings, hungry animals, deadly poppy fields—and finally arrives at Emerald City, where she and friends win an audience with the Wizard of Oz. The Wizard proves both capricious and exacting, demanding that Dorothy kill the Wicked Witch of the West in exchange for homeward passage.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Fans of Baum’s original novel will be pleased to learn that writer Eric Shanower has restored many scenes trimmed from the MGM film. In issue two, for example, Shanower relates the Tin Man’s backstory in considerable detail, describing the curse that drove the woodcutter to chop off his limbs, head, and heart until all of his flesh had been replaced with metal. Shanower also follows Baum’s novel for the famous poppy scene, which occurs at the end of issue three. Though Dorothy and the Lion succumb to the red flowers’ narcotic effect—just as they do in the movie—the Scarecrow and Tin Man enlist an army of field mice to drag their friends to safety rather than appeal to the Good Witch of the North for help. These seemingly small changes have a profound effect, resulting in a story that’s darker and more complex than the film version that so many of us know by heart.

Shanower’s fidelity to the original novel also emphasizes the Americaness of Baum’s conceit. As Shanower explains in a companion essay, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz “wasn’t the first time an American author had created a fantasy using American themes, setting aside elves, fairies, and the trappings of medieval Europe. But it was the first time an American fairy tale struck a lasting chord with readers and took its place on the shelves of great American literature.” (See The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Sketchbook, a free pamphlet released last year by Marvel.) Though one might quibble with Shanower’s historical claims—Washington Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent introduced readers to Rip Van Winkle and Ichabod Crane in 1820—his basic assertion is right on the money: the story endures because its characters are quintessentially American. Dorothy, for example, may embody universally appealing traits, but in the Shanower/Young retelling, she comes across less as a plucky Everygirl and more as a plain-spoken kid from Kansas who’s blunt and unsparing in her observations, yet stout-hearted, resourceful, and tolerant. Her companions, too, possess courage and loyalty in abundance—both universally admired qualities—but it’s their quest for self-improvement that seems so utterly American, especially in their unshaking belief that Oz can transform their lives with a single gesture.

Shanower’s fidelity to the original novel also emphasizes the Americaness of Baum’s conceit. As Shanower explains in a companion essay, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz “wasn’t the first time an American author had created a fantasy using American themes, setting aside elves, fairies, and the trappings of medieval Europe. But it was the first time an American fairy tale struck a lasting chord with readers and took its place on the shelves of great American literature.” (See The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Sketchbook, a free pamphlet released last year by Marvel.) Though one might quibble with Shanower’s historical claims—Washington Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent introduced readers to Rip Van Winkle and Ichabod Crane in 1820—his basic assertion is right on the money: the story endures because its characters are quintessentially American. Dorothy, for example, may embody universally appealing traits, but in the Shanower/Young retelling, she comes across less as a plucky Everygirl and more as a plain-spoken kid from Kansas who’s blunt and unsparing in her observations, yet stout-hearted, resourceful, and tolerant. Her companions, too, possess courage and loyalty in abundance—both universally admired qualities—but it’s their quest for self-improvement that seems so utterly American, especially in their unshaking belief that Oz can transform their lives with a single gesture.

Though Shanower clearly “gets” Baum’s original, he is, at times, a little too respectful of the source material. He relies heavily on an omniscient narrator, e.g. telling us where Dorothy and her companions sat down to eat lunch, or where they spent the night. Sometimes these voiceovers are effective, relating incidents that are too tangential to main plot to merit further development; other times, the artwork does a fine job of showing us what’s happening, making the voiceovers redundant. My other criticism (a minor one, to be sure), is that Shanower makes no attempt to update the language. I’m grateful that Dorothy hasn’t been transformed into a l33t-speaking tween, but there’s a stiffness and formality to the dialogue that seems ill-suited to word balloons.

The artwork, on the other hand, is gorgeous. Colorist Jean-Francois Beaulieu deftly manipulates a soft palette of greens, browns, and blues to create a variety of moods and landscapes, from the menacing darkness of a twilight forest to the blinding brightness of a midday river crossing. The poppies are especially astonishing when they first appear, as their bright, unadulterated red contrasts sharply with the blues and greens found elsewhere in the first three issues. (N.B. for Judy Garland fans: Dorothy’s shoes are silver, as in the original novel.)

Skottie Young’s designs are equally distinctive. Young’s characters look slightly unfinished, their rough, energetic linework on prominent display. Such a makeover is welcome; I’ve never been a big fan of W. W. Denslow’s original illustrations, which always seemed too soft and domesticated for Baum’s dark fairy tale. By placing Denslow’s character designs side-by-side with Young’s, one can see just how dramatic and effective that transformation is. On the left is a plate from the 1900 edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz; in the middle, an illustration from issue three of the Shanower/Young version; on the right, a page from issue one:

Young has given Denslow’s smiling, robotic Tin Man an extreme makeover that includes a dramatic mustache and furrowed brow that reminds us of that the Tin Man was once a flesh-and-blood man. For the Scarecrow, Young adopts a different tact, making the character look less human by emphasizing the Scarecrow’s ill-fitting outfit and burlap bag head. But the most effective transformation is Dorothy, who is no longer a stolid lass with long braids (as in Denslow’s illustrations) but a scrappy, skinny girl whose upturned chin and gangly limbs exude determination.

Will kids want to read The Wonderful Wizard of Oz? I feel a little uncharitable even asking the question, given the consummate skill with which this series has been made. Young readers may enjoy the illustrations (especially the Cowardly Lion, who’s been transformed into a round, appealing ball of fur). But I’m not certain that the under-ten crowd will appreciate the nuanced storytelling, especially if they’ve seen MGM’s dazzling, Technicolor version. Tweens and teens seem like a better audience for this comic; if anything, the story’s dark strangeness will give them a new appreciation for Frank L. Baum’s work.

Issues 1-4 are available now; issue five will be released on April 8, 2009. Images © 2009 Marvel Comics and © 2001 HarperCollins.

Filed under: Reviews, Uncategorized

About Katherine Dacey

Katherine Dacey has been reviewing comics since 2006. From 2007 to 2008, she was the Senior Manga Editor at PopCultureShock, a site covering all aspects of the entertainment industry from comics to video games. In 2009, she launched The Manga Critic, where she focuses primarily on Japanese comics and novels in translation. Katherine lives and works in the Greater Boston area, and is a musicologist by training.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

ADVERTISEMENT